There is a growing concern in education, safeguarding, and mental health fields about the influence of figures like Andrew Tate and others who appeal to boys and young men. It can feel easy — and even comforting — to say the problem starts with these influencers. But when we place the blame solely on external personalities, we risk missing what is actually happening beneath the behaviour.

The incel identity, and the behaviours associated with it, do not begin with ideology.

They begin with pain.

They begin with attachment wounds — the parts of a young person that did not feel chosen, secure, mirrored, supported, encouraged, or understood when they most needed to be. Influencers do not create that wound. They simply give language to it. They speak into the ache.

And when a young person finally hears someone name their hidden shame or loneliness — even in a distorted way — it can feel like belonging.

This is why arguments, lectures, and blame rarely shift these identities.

They speak to the behaviour, not the wound beneath it.

A Shame-Based Identity, Not Defiance

Many young people drawn into incel thinking have experienced:

- Emotional neglect (even in caring families)

- Repeated feelings of rejection or invisclusion

- Difficulty forming social or romantic connections

- A lack of emotionally present male role models

- Limited emotional language or space to talk about loneliness

The result is shame — the sense of “I am not wanted as I am.”

Shame is unbearable to sit with alone.

So the psyche builds a defence:

“The problem is not me. The problem is women. The problem is society. The problem is everyone else.”

This is not arrogance.

This is protection.

It is the nervous system trying to survive emotional pain.

The Self-Awareness Scale

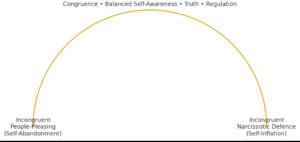

We can understand this more clearly by looking at the Self-Awareness Scale:

- On one end of this scale, we find people-pleasing — the collapse of the self to gain approval.

- On the other end, we find narcissistic defence — the inflation of the self to avoid shame.

- In the centre is congruence — the grounded ability to remain connected to oneself and others at the same time.

We all move along this scale.

No one is fixed to one end.

This is not about diagnosing, labelling, or blaming.

It is about recognising:

- what our protective patterns are,

- what they are protecting us from,

- and how they impact the relationships around us.

Self-awareness is the goal.

Not perfection. Not performance.

Just the gentle capacity to notice ourselves.

Why Blame Makes Things Worse

When educators, parents, or professionals respond to incel thinking with:

- Shaming

- Ridiculing

- Moralising

- Outrage

we recreate the same relational injury that led to the identity in the first place.

If the wound is shame, and we respond with shame, the wound deepens.

If the defence is “I am unsafe with others,” and we respond with hostility, we prove the defence right.

Blame recreates the very dynamics that caused the wound.

To teach congruence, we must model it.

What Helps Instead?

Young people heal through:

- Attuned relationship, not correction

- Curiosity, not confrontation

- Emotional language, not embarrassment

- Grounded adult regulation, not adult frustration

- Belonging, not behavioural compliance

We must be the calm nervous system they can borrow from until they learn to regulate their own.

This is the heart of trauma-informed safeguarding.

A Final Reflection

The word education comes from the Latin educare and educere —

meaning to draw out from within, not to impose from the outside.

Our role is not to fix, shame, frighten, or force young people into maturity.

Our role is to help them meet themselves — with dignity, safety, truth, and compassion.

Because when a young person feels seen, valued, and accepted, they no longer need armour to be in the world.