Shame Disguised as Motivation

Let’s Talk About Shame Disguised as Motivation

Something’s been showing up repeatedly in my feed — and it needs to be addressed.

Images of disabled people being used as inspirational tools to shame others:

“If I can work with no hands, so can you.”

“If you can scroll on social media, you can work.”

Let’s be clear — this is not empowerment. This is shame-based bullying. And it is deeply harmful.

This narrative pushes a dangerous message:

That your struggle is invalid because someone else has it “worse.” That you should stop claiming disability support. That you’re lazy.

It’s not just unkind — it’s wilfully ignorant.

It assumes that all disabilities are visible.

That trauma doesn’t exist.

That chronic illness, anxiety, neurological differences, or exhaustion aren’t real.

That everyone who can physically touch a screen is mentally and emotionally well enough to function in a workplace.

This is not person-centred thinking.

No two people are the same.

No two stories are the same.

Recovery looks different for everyone. Some people may never recover. That doesn’t make their life less valuable or their needs less real.

If someone has overcome incredible odds and is now able to work — that’s a story worth honouring. For them. But using their story to shame others is not inspiring. It’s violent.

What people need is:

• Compassion

• Care

• Support

• Time

• And the right to be believed.

So if you’re tempted to share one of those posts, stop and ask:

“Is this helping — or is this hurting?”

To those who are struggling quietly, feeling unseen, invalidated or shamed by these messages — I see you. You don’t need to prove your pain to anyone.

You matter.

Your experience is real.

And you are not alone.

Perhaps one of the hardest parts to witness is this:

Why do people make comparisons with others who are suffering — to judge what they cannot possibly understand?

Because judgment feels safer than empathy.

Empathy requires courage. It asks us to sit beside someone in their pain without fixing it, ranking it, or pushing it away. That’s confronting — especially for those still running from their own wounds.

Suffering holds up a mirror.

And for many, that mirror is unbearable.

To see someone struggling — especially when that struggle is raw, messy, invisible, or ongoing — reflects back all the fears we try to keep hidden:

What if I break down? What if I need help and no one comes? What if I’m not strong enough?

So instead, some people turn away. Or worse, turn on those who are already hurting.

To say, “You should be coping better.”

To imply, “It’s your fault.”

To believe, “That will never be me.”

But here’s the truth:

No one escapes life untouched. And when we stop judging and start listening, we begin to heal — together.

And while we’re here — it’s worth asking: Who is sharing these posts, and why now?

Because I don’t believe in coincidence.

These “inspirational” shame posts often surface during political debates about disability benefits, just as media headlines begin to push narratives about “scroungers” or “fraudsters.” They don’t appear in isolation — they rise alongside policy shifts and public messaging designed to divide, distract, and dehumanise.

We must ask:

Who benefits from this narrative?

Certainly not those who are struggling.

It’s not motivation — it’s manipulation. And we need to see it for what it is.

“The test of our humanity is not how we treat the strong, but how we stand with the wounded.”

The Other Side of the Desk: The Dehumanising Reality of the Benefits System

When people think about "the benefits system," there’s often a polarised narrative. Some imagine it as a safety net abused by people who don’t want to work, who live off the state in comfort. Others, like me, know the truth firsthand — and it’s not just a different reality, it’s a soul-destroying one.

Accessing benefits in the UK isn’t just about filling out forms. It’s about leaving your dignity at the door. It’s about standing in a system that echoes your worst inner fears — that you are worthless, a burden, and somehow to blame for needing help.

Shame thrives here.

So does silence.

Because talking about the true cost of being in the system — emotionally, psychologically, and even physically — opens you up to more judgement. The very act of seeking support is treated as evidence of your failure, rather than your strength.

Many people believe that claiming benefits is easy, that people do it to ‘have an easy life’. But the truth is, being on benefits loudly announces to the world — and to yourself — that you've somehow ‘failed’ at life. And that message isn't subtle. It's delivered daily through the structure of the system, the tone of letters, the degrading interviews, and the suspicion that seems baked into every interaction.

The System Dehumanises

It’s not set up to support healing or recovery. It's designed to test, measure, and invalidate. The support people are told to seek — after illness, trauma, abuse, or loss — comes at a cost: invasive assessments, impossible expectations, and repeated humiliations. And the message is clear: you must prove your suffering is real, again and again.

The impact on a person’s nervous system when they are reliant on the benefits system cannot be overstated. Living with the constant threat of your income being reduced or removed — often on the whim of successive governments — places the body in a prolonged state of stress. The sympathetic nervous system is activated, keeping individuals stuck in survival mode, flooded with cortisol and adrenaline. Over time, this chronic dysregulation leads to exhaustion, burnout, and serious health consequences. It erodes a person’s sense of safety and belonging, disconnecting them from hope, self-worth, and even from their own body. What’s often dismissed as ‘laziness’ or ‘lack of motivation’ is in reality a nervous system collapse — a trauma response from years of systemic threat and invalidation.

What’s worse is the belief that if someone is struggling — emotionally or financially — they shouldn’t be allowed to enjoy life. There’s an unspoken rule that if you're not contributing to the economy, you should be invisible, silent, and sad. God forbid you're seen smiling at a café or sharing a happy photo online — it becomes evidence that you're not struggling "enough."

Disconnection as a Survival Strategy

Many people in the system have learned to disconnect from themselves just to get through the day. And yes, in some cases, there are people who’ve given up, who turn to substances or sleep away the hours — but what’s never asked is why?

Often, it’s years of trauma and systemic failures that brought them to that place. People don't just give up — they’ve been worn down. Many have been abused, neglected, and repeatedly failed by the very institutions meant to protect them. And instead of support, they’re met with suspicion.

Judgement Masquerading as Help

Professionals working within the system — assessors, case workers, decision-makers — are often themselves disconnected and dysregulated. Not always, but often. Empathy isn’t valued. Efficiency is. Compassion is replaced with a checklist. And the people who sit across the desk from you — making decisions about your life — have been trained to question your credibility, not your pain.

Why It Matters

This isn’t just about being kind for kindness' sake. Science shows that compassion heals. Trauma-informed, person-centred support enables people to recover faster, become more resilient, and move forward. If the system were built on understanding and care, fewer people would get stuck in it.

But that’s not the goal. Because when someone starts to get better — when there’s even a flicker of hope or recovery — the support is pulled away. They’re expected to return to full capacity immediately, cover impossible costs of living, and function as though the past never happened. Unsurprisingly, many end up right back where they started, only more depleted.

It Doesn’t Have to Be This Way

Just like our education system is beginning to question outdated, punitive policies, the benefits system needs radical change. We need to build structures that see people as human — not numbers, not claims, not problems to solve or weeds to pull.

We need to reframe success — not as how quickly someone can ‘get off benefits,’ but how fully they can rebuild their lives with dignity and hope. Until then, we’ll keep trapping people in cycles of shame and survival.

Let’s start talking about this openly.

Let’s challenge the narratives that blame individuals for the failure of systems.

And let’s remember: every single person in need of support is a human being — no less worthy, no less valuable, no less deserving of compassion than anyone else.

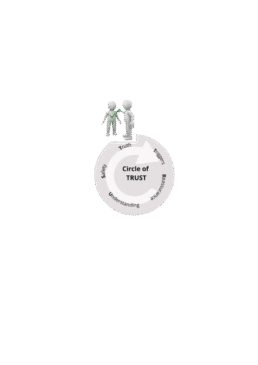

TRUST & RAPPORT

At A Positive Start CIC, we believe that healing doesn’t begin with theory. It begins with safety. And safety begins with TRUST—a trauma-informed framework rooted in lived experience, nervous system science, and human compassion.

For those living with complex trauma, especially from early childhood, being in a constant survival state often becomes the default. Many of our responses—what we label as fight, flight, freeze, or fawn—are not choices. They are reflexes. And most of them happen outside of our awareness.

The TRUST framework was born from this understanding. It’s how we work, how we train, and how we create the conditions for regulation, recovery, and growth—for both practitioners and clients.

T – Trigger Recognition

For individuals who have spent most (or all) of their lives in survival mode, triggers are rarely obvious. Often, they are subtle, implicit, and automatic. Someone may find themselves suddenly overwhelmed, shut down, or in conflict—without a clear reason why.

At A Positive Start, we recognise that when someone is triggered, they are no longer anchored in their body. They’re dysregulated. And because they’ve never had the experience of their needs being named, validated, or met, they may not know what they need, or how to meet those needs.

This state of being unanchored often drives people to seek comfort externally—through food, alcohol, cigarettes, medication, or other temporary soothers. These offer short-term relief, but not safety. As Dr. Wayne Dyer famously put it, it’s like losing your keys in the house and looking for them outside. You won’t find what you need in the wrong places.

To truly regulate, we need co-regulation—which leads us to the next step.

R – Reassurance

When someone is dysregulated, they need another person’s nervous system to help them settle. This is how we learn to regulate—through co-regulation first, then self-regulation later. It’s not a flaw. It’s how humans are wired.

Reassurance is a powerful tool. Words like “You’re safe here,” or “I’m with you,” can soothe the chaos in someone’s system. Conversely, language like “Pull yourself together” or “You’re just attention-seeking” deepens dysregulation and reinforces shame.

And this is key: what may appear as attention-seeking is, in fact, connection-seeking. From a survival state, the nervous system is searching for safety. Reassurance is the answer. It restores co-regulation, it anchors, and it calms.

U – Understanding

True trauma-informed practice requires understanding—not only of what trauma is, but what it feels like. When we understand the nervous system states—fight, flight, freeze, fawn—we can respond with compassion instead of judgement, curiosity instead of control.

Sadly, many institutions (including schools) still default to punitive measures. But punishment retraumatises those with complex trauma. It reinforces the very beliefs trauma planted: “I’m bad,” “I don’t matter,” “There’s something wrong with me.”

Instead, we need to see the unmet need beneath the behaviour. Understanding creates connection. Connection creates calm.

S – Safety

Safety is not just about the environment. It’s about how the environment feels. This is called Neuroception—our unconscious scanning of safety and threat. If someone senses incongruence, judgement, or inauthenticity, their body will not relax.

Safety is built through consistent compassion, reliable presence, and an atmosphere that feels emotionally safe. When someone feels seen, heard, and not judged—they can start to trust.

T – Truth

Without truth, there can be no trust. And without trust, no safety. And without safety, no healing.

Truth here means congruence. Genuineness. Transparency. It means that the practitioner shows up authentically—not perfectly, but present. Because healing requires a relationship that feels real.

At A Positive Start, all our practitioners and therapists are first taught how to recognise when they are dysregulated. They learn how to regulate themselves before supporting others. This is essential, because TRUST only works when the person leading is regulated.

From TRUST to RAPPORT: The Next Step in Healing

Once we can offer TRUST, we can begin to cultivate RAPPORT—not just with others, but within ourselves. At A Positive Start, we say:

Healing begins with self-care. And self-care starts within.

Here’s how we guide people through RAPPORT:

R – Recognition

We start by recognising what’s happening in our nervous system. Are we calm, overwhelmed, shutting down? Can we name the state we’re in? Recognition is the foundation of self-awareness.

A – Awareness

This goes deeper—becoming aware of our patterns, our triggers, our protective parts, and the stories we’ve carried. Awareness builds the bridge between experience and understanding.

P – Process

We can’t bypass the feelings—we must move through them. In this stage, we begin to feel, name, and process what’s been held in the body for too long.

P – Practice

Healing is not a one-off insight. It’s a daily practice. Breathwork, grounding, journaling, mindful movement, compassionate self-talk—all become part of our regulation toolkit.

O – Observe

We begin to notice changes in our responses, our thoughts, and our nervous system. We become the compassionate observer of our inner world, rather than the judge.

R – Reflect

We take time to reflect on what’s working, what we’ve learned, and how far we’ve come. Reflection solidifies growth.

T – Transformation

This is where the shift happens. Not that the past disappears—but our relationship with ourselves changes. We become less reactive, more regulated, more anchored in truth and safety.

Living the Practice

At A Positive Start CIC, we don’t just teach these frameworks. We live by them. TRUST and RAPPORT are woven into everything we do—our training, our workshops, our client care, and our team support.

Because people heal in safe spaces.

And safe spaces are built by people who are committed to self-awareness, congruence, and compassion.

If you’re a practitioner, educator, or someone supporting others:

Let this be your invitation to embody #TRUST.

To offer #RAPPORT.

To become the regulated, compassionate presence that makes healing possible.

Applied TRUST & RAPPORT Workshop

Learn how to create emotional safety - for others and for yourself

Written by Deborah J Crozier | Founder of A Positive Start CIC

Person-Centred Counsellor & Trauma-Informed Practitioner

Why People-Pleasing isn’t Always Politeness

Most people don't wake up deciding to abandon themselves. They learn to do it over time-because it was safer to appease than to upset, easier to please than to risk rejection.

This is called the fawn response. And it's not about kindness. It's about survival.

The fawn response is a trauma-informed term for a survival adaptation where a person automatically appeases, pleases, or accommodates others to stay emotionally or physically safe.

Coined and popularised by therapist Pete Walker in the context of Complex PTSR

(C-PTSR), fawning is not just 'being nice'-it's a deeply ingrained strategy often rooted in childhood relational trauma.

Children are hard wired to attach. When connection is conditional, inconsistent, or threatening, they adapt. If love came with strings attached, if calm depended on keeping someone else happy, or if emotional needs were met with criticism or withdrawal, the child may have learned: "I'll be OK if I make you OK."

That becomes the internal rulebook:

- Don't rock the boat.

- Don't ask for too much.

- Don't be a burden.

- Don't be angry, sad, or real.

- Just be easy, helpful, invisible- even if it costs you.

Fawning can look like:

- Chronic people-pleasing and over-apologising

- Difficulty saying no or setting boundaries

- Feeling guilty for having needs

- Hyper-attunement to others' emotions

- Suppressing your truth to avoid conflict

- Feeling 'liked' but not truly known

- Rescuing or fixing others, often at your own expense

Fawning isn't a personality trait - it's a learned defence mechanism. There’s a difference between politeness and fawning.

Politeness is rooted in choice and mutual respect, whereas fawning is rooted in fear and appeasement.

Politeness maintains self and others - Fawning abandons self to preserve connection.

Politeness allows boundaries - Fawning suppresses them to stay safe.

Fawning is often a blended nervous system state-a mixture of: -

Sympathetic arousal (urgency, hyper-vigilance) and Dorsal vagal shutdown (self-abandonment, loss of voice) with an attempt to engage the social engagement system (smiling, soothing others, appeasing).

It's a brilliant adaptation to early environments where being your full self wasn't safe.

Healing doesn't mean becoming selfish-it means becoming sovereign.

Here's how we begin:

1. Somatic Awareness: Notice when your body feels tight, small, breathless, or fake.

Ask: What do I really feel?

2. Safe Boundaries: Practice saying no in low-stakes environments.

Try: 'Let me get back to you.'

3. Inner Child Reassurance: Fawning often

comes from the child self.

Gently say: 'You don't have to shrink to be safe.'

4. Voice Work: Speak up, hum, or sing. It activates the ventral vagus nerve and supports regulation.

5. Relational Repatterning:

Seek relationships where your 'no' is honoured and your presence is valued.

In conclusion,

The fawn response is not a flaw-it's a wound. A strategy. A child's best attempt at love and safety.

Now, as adults, we get to update the story: 'I am allowed to take up space. I don't need to abandon myself to be loved.' And that's not selfish. That's sacred.

Abandonment: More Than Being Left Behind

There are some wounds we carry that don’t leave visible scars.

Abandonment is one of them.

It’s not always marked by a door slamming shut or someone walking away.

Sometimes, it’s the quiet absence in a room full of people.

The unanswered cry.

The parent who was there in body, but unreachable in spirit.

The moment you realised you had feelings no one could hold.

Abandonment isn’t just about who left.

It’s about who didn’t show up emotionally, who didn’t see you, who didn’t protect you.

And over time, that wound doesn’t just sit in the past—it weaves itself into the present, shaping how we love, how we cope, how we see ourselves.

If you’ve ever felt like you were “too much” or “not enough”…

If you’ve worked hard to earn love or acceptance…

If you’ve found yourself chasing connection or fleeing it before it can break again…

You are not alone.

This blog is a compassionate space to explore:

- What abandonment really is

- Why it’s so impactful

- How it can shape the nervous system and sense of self

- And most importantly—how it can be healed

You were never meant to carry this weight alone.

Let’s begin gently.

Abandonment isn’t always dramatic. Sometimes it’s quiet. Subtle. Repeating.

It’s a door that never opens again. A parent who was there, but never really with you. A friend who ghosts. A loved one who stays, but disconnects.

For many people, abandonment is not a one-time event—it’s a felt experience that becomes part of their inner landscape. Understanding it is the first step toward healing.

Abandonment is the experience of perceived or real disconnection from someone we depended on—emotionally, physically, or psychologically. It can happen in many ways:

- A parent leaves the family.

- A caregiver is emotionally unavailable or inconsistent.

- A loved one dies, and the child is left to manage grief alone.

- A friend or partner withdraws without explanation.

- A child is left to care for their own emotional needs, consistently.

Often, it’s not about someone walking out the door—it’s about someone not walking in emotionally.

A parent who feeds, clothes, and houses a child—but never asks how they’re feeling.

A partner who’s physically present, but unresponsive or indifferent to your pain.

A professional who labels you without listening, and in doing so, leaves you unseen.

These are all forms of abandonment—relational, emotional, and spiritual.

Abandonment wounds strike at the heart of our biology.

1. Attachment Theory

From birth, humans are wired for connection. According to Bowlby and Ainsworth, secure attachment builds when a caregiver is consistently available, attuned, and responsive.

When those needs aren’t met, children adapt. They may become avoidant, anxious, or disorganised in their attachment styles—carrying these patterns into adulthood.

2. The Nervous System

Abandonment activates the sympathetic nervous system (fight/flight) or dorsal vagal (freeze/shutdown) responses:

- Fight: Confrontation, control, anger, defensiveness

- Flight: Escape, avoidance, busyness, perfectionism,

- Freeze: Shut down emotionally, dissociate, numb.

- Fawn: Appeasement, people-pleasing, self-abandonment

Over time, this shapes neuroception—the brain’s unconscious scanning for danger. A person with abandonment trauma may perceive rejection even in safe relationships, not because they are irrational, but because their body has been trained to expect disconnection.

3. Cortisol & Brain Development

Children raised with chronic emotional neglect often have higher baseline cortisol levels, affecting brain areas like:

- Amygdala: Fear and emotional reactivity

- Hippocampus: Memory consolidation

- Prefrontal Cortex: Emotional regulation and reasoning

This means abandonment can literally shape the brain—but also that healing can reshape it too (thanks to Neuroplasticity).

People with unresolved abandonment trauma may experience:

- Chronic fear of rejection or not being “good enough”

- Anxiety when someone pulls away or is silent

- Difficulty trusting others’ intentions

- People-pleasing, over-giving, or rescuing

- Sabotaging relationships before they end

- Deep shame or belief that they are “too much” or “not enough”

Because abandonment is often preverbal or accumulative, it’s stored somatically. The body becomes the holder of the wound:

- A tightening in the chest when someone withdraws

- A sinking feeling in the stomach when ignored

- A sudden urge to run, argue, or shut down

- Feelings of worthlessness that don’t match your logic

This is why healing must go beyond talking—into the body, into regulation, into safe relational experiences that slowly rewrite the story.

How We Begin to Heal?

- Name the wound. Recognise where abandonment shows up in your life now—and where it began.

- Regulate the nervous system. Practices like EFT, breathwork, orienting, or somatic self-touch can soothe the internal alarm.

- Build safe connection. Choose relationships (therapeutic or personal) where your presence is welcomed and your absence is noticed.

- Reparent the abandoned parts. Speak to the child within you as the parent you needed. Offer presence, not perfection.

- Update the story. You were never too much. You were never unlovable. You were responding to the ache of being left without a map.

Abandonment is not a flaw in you. It’s a fracture in the foundation of safety—and fractures can heal.

The younger you that was left behind still waits—not for the person who left, but for you.

To see her. To hold her. To whisper:

“You are safe now. You are never alone again. I’m staying.”

See the Human

Thirty years ago, I was a statistic. A survivor of domestic violence. A mother judged as too damaged to recover. A woman professionals expected would fail—and whose children were predicted to follow suit.

They were wrong.

Today, my children are thriving adults: graduates, home-owners, parents, partners, professionals. Societies measure of success. Good people, safe, healthy with secure lives. Empathic, compassionate regulated humans mindful of the impact they have on others and the world around them - their nervous systems mostly in a Ventral state - my measure of success. Yet, according to the system, we should still be 'in it.' But we’re not—and haven’t been for decades.

Why? Because we had space to heal. We had truth, openness, and a determination to rewrite our story. But we also had to fight for that. And too many still do.

I speak out to break the stereotypes. To challenge the mask. To dismantle the outdated, shame-based sayings like “don’t air your dirty laundry in public” or “don’t overshare.” These phrases were never about protection—they were about silence. About control. About keeping the truth hidden to protect reputations, not people.

Speaking out is not oversharing. It’s reclaiming. It’s refusing to carry shame that never belonged to us in the first place. It’s saying: I lived through this. I survived this. And I will not be quiet about it.

Because silence serves the abuser. Truth sets us—and others—free.

What’s Missing in Domestic Violence Support?

As a trauma-informed practitioner, I work with people who’ve experienced what I did. And I see a repeating pattern: the system sees the behaviour, not the human. A mother who stays is labelled weak or incompetent. A father who shuts down is deemed neglectful. Children are removed from homes not because they are unsafe, but because their parent is traumatised.

But trauma doesn’t make someone unfit to love. It doesn’t erase their bond with their child.

We must begin asking:

- What’s happening *within* the individual?

- What’s going on in their nervous system?

- What survival strategies helped them stay alive, even if from the outside it looks like passivity?

- What part of their story has been choice—and what part has been outwith their control?

And most importantly—who would ‘choose’ violence?

Abusers manipulate. They fool victims. And they often fool the very systems and those employed to serve in them, designed to protect those victims.

That’s not weakness. That’s psychological warfare.

When victims stay, it’s not because they’re blind—it’s because they’ve been systematically broken down, gaslit, isolated, and emotionally hijacked. And still, many get out. Still, they rise. And that deserves recognition, not criticism.

The Quiet Dysregulation of Professionals

Here's a difficult truth: I know social workers, support workers who are dysregulated, silently suffering behind closed doors. Burned out. Pressured. Grieving. Exhausted. And I understand why—they are working in a system that doesn’t make space for their wellbeing either.

But here's the danger: two dysregulated adults—one professional, one victim—do not create safety. They create chaos. Fear. Mistrust.

So we must ask:

How do professionals manage their own nervous systems?

How do they know whether their decision is being made from regulation or reactivity?

We can’t afford to ignore this. The cost is too high—for families, for children, and for the professionals themselves.

What the System Predicted for Us… and the Truth

According to the projections made by professionals back then, my children and I should still be in the system. By their standards, our trajectory was bleak. We were expected to fail.

But here's the reality:

- My children are now fit, healthy, successful adults.

- They’ve graduated university, hold secure jobs (one runs their own business), and live in safe, stable homes.

- They are in healthy relationships, free from addiction, criminal activity, or the trauma cycles we were expected to repeat.

- They are kind, thoughtful individuals who contribute positively to society.

I am incredibly proud of them.

We didn’t stay in the system. We moved away from the abusive person—almost three years later than we could have, because the courts forced continued contact with the abuser. But when that ended, I focused entirely on their wellbeing. We talked openly. I took responsibility for my own healing and safety. And we rose.

The Prevention Paradox

It’s interesting to me that when I first applied for funding to support prevention, I was told, “We don’t fund prevention.”

Let that sink in.

We don’t fund preventing trauma.

We wait until people are in crisis, broken, or in danger—and then we pour money into emergency responses.

It’s also interesting how, when you create a prevention-based action plan—like A Positive Start—you’re told that you can’t prove it worked.

You’re told that the positive outcome might have happened anyway, so you can’t claim credit for the transformation you supported.

And yet, no one ever questions whether a child removed from their parent might have been fine if we’d offered the right support instead.

No one challenges whether punitive responses are effective—only prevention.

Isn’t it a shame those same theories of “we can’t prove what didn’t happen” aren’t applied at the other end?

Prevention gets interrogated. Punishment gets assumed effective.

We need to flip that logic—before more families are harmed.

It was the same story when we recently applied for funding for our SPACES Project—Separated Parent And Child Emotional Support.

We were turned down.

Why? Because one of the panel members also sat on the Children’s Panel and felt it “wasn’t appropriate” to support parents whose children had been removed.

Let that sink in.

As far as they were concerned, if your child was removed, then it was for good reason. Case closed.

Essentially:

“We’re right. You deserved it. Now suffer in silence.”

How egotistical is that?

Where is the humanity?

Where is the understanding that trauma can cause behaviours that don’t define a person’s capacity for love, growth, or redemption?

If we truly believe in safeguarding children, then we must also believe in supporting parents—especially those willing to do the work, face the truth, and rebuild.

Otherwise, we’re just perpetuating pain and calling it justice.

They weren’t able to see that they might be wrong.

Or—even if they were right—that suffering still occurs.

And that suffering, left unsupported, only perpetuates the very issues we claim to want to solve.

When a parent loses a child—whatever the reason—they don’t stop being human. They don’t stop needing understanding, healing, or help.

To deny them support isn’t protective—it’s punitive.

And punishment, without compassion, never leads to change. It just adds another layer of trauma.

If we truly care about protecting children, we need to care just as much about healing the people they came from.

The Cost of Getting It Wrong

Let’s talk about the cost of all this—emotionally and financially.

The emotional toll on families wrongly judged, children separated without cause, and parents labelled rather than supported is immeasurable.

But there are financial consequences too: repeated police involvement, court proceedings, supervised contact arrangements, welfare officers, social worker interventions, housing teams, and more. My family was rehoused out of area for our safety—an enormous cost in itself, rather than removing one abusive person, they relocated the victims and then shared our new address openly in court in front of the perpetrator, rendering the move entirely pointless.

Why it Happens Again

To be clear, my children were never going to be removed from my care. I had already left the situation before services became involved. It may have been a different story if I hadn’t taken a different route.

If, like many survivors of domestic violence I had returned to that abusive partner or found myself in another abusive relationship, it wouldn’t have been because I didn’t want better. It would have been because of how trauma works.

Research shows that when we’ve lived in survival mode, we often mistake familiarity for safety—not because it’s safe, but because our nervous system has been wired to expect the unpredictable.

When you don’t truly know what safety feels like in the body, you’re not necessarily drawn to peace—you’re drawn to what you know.

And often, without conscious awareness, the body tries to complete an arousal cycle that was never resolved.

This can lead survivors to unknowingly repeat patterns—not out of weakness, but out of the nervous system’s attempt to finish what it started.

This isn’t failure. It’s a biological survival response in need of understanding—not judgement.

A trauma-informed approach rooted in lived experience isn’t just more compassionate—it’s far more cost-effective. It could save millions in public funds, while helping families heal instead of break.

Lived Experience, Labels, and Curiosity

They told me I was 'farthest from the labour market.' That I might never fully recover. That my children were 'at risk.'

None of it came true.

What they didn’t see was that I was also deeply capable. Reflective. Committed to healing. Determined to break the trauma cycle. I took my recovery into my own hands—and what emerged became ‘A Positive Start - initially, it was our plan for a positive start - that eventually became a community interest company committed to trauma-informed education and relational safety.

I chose curiosity over labels. I got curious about what my body was holding, what my story was saying, and what healing might look like if I gave myself permission to feel instead of fear.

Reflections on Judgement and Power

“People in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones.”

That’s what comes to mind when I think back to some of the professionals who sat in judgment over me.

Those who assumed they understood me based on paperwork, not presence.

Those who overlooked my strength, but also failed to grasp the danger I was facing—until it was too late.

One of them worked in a “secure” supervised visitation facility.

The place where my child was abducted—right out from under their watch.

They underestimated my abuser.

They didn’t listen.

They dismissed the severity of the threat, because it didn’t fit their framework.

But even more so—they underestimated me.

They imagined I was “less than” because I was in a traumatising situation.

They were wrong.

I wasn’t weak. I wasn’t incapable.

I was oppressed. I was traumatised. And still, I was doing everything I could to protect my children.

Being traumatised is not the same as being unsafe.

Being abused is not the same as being unfit.

And surviving violence does not make you less—it often means you’ve had to become more than anyone should ever have to be.

A Sobering Reminder

Everything I’ve described—the judgement, the labelling, the assessments, the forced rehoming, the emotional scrutiny—

was reserved for me. The victim.

I was the one under the microscope. I was the one expected to prove my worthiness as a parent, a human, a survivor.

And the perpetrator?

He walked away.

Unaffected. Untouched by the same systems that dissected me.

Free to continue the performance, the manipulation, the abuse—often enabled by the very structures meant to protect.

This is the injustice so many survivors face.

We are left to clean up the mess, carry the blame, and rebuild from the ruins—while those who caused the harm are rarely held to account in the same way.

What Needs to Change

We need to stop treating trauma as a problem to be managed, and start treating it as a story to be understood.

Let’s build:

- A new trauma-informed training initiative for social workers and safeguarding teams.

- Honest conversations about dysregulation in professionals.

- Assessments that prioritise attachment, emotional context, and support, not just risk.

And let’s bring lived experience into the conversation—not as an afterthought, but as a guide.

Final Thought

If we want to change lives, we have to change how we see them.

Start with compassion. Start with connection. Start by seeing the human behind the behaviour.

Thirty years ago, I didn’t need judgment. I needed understanding, compassion, and empathy.

I needed someone to recognise what it took to survive.

To acknowledge that I had got myself and my children to safety.

To respect that I was still standing—still living—even when someone had tried to end me.

I didn’t need judgement.

I needed to be seen.

That’s why I do this work now. Because understanding can change a life—and sometimes, that life goes on to help thousands more.

#TraumaInformed #DomesticViolence #SocialWork #LivedExperience #APositiveStart #Safeguarding #CompassionateCare #Reform

IMG_9168

Real Safety - The Foundation of Healing

“Feeling safe is the treatment, creating safety is the work.” – Dr. Stephen Porges

We often hear the word safety in trauma-informed spaces. But what does it really mean to feel safe? And how do we know when it’s present—not just talked about or implied, but truly felt in our bodies, our relationships, and our nervous systems?

Safety is more than a protocol or a professional tone. It’s more than a laminated policy or a clinical smile. Real safety is embodied. It’s felt.

What Safety Is -

Safety is kind.

Safety is compassionate.

Safety is understanding, not performative.

Safety sees you, hears you, and honours what’s happening for you, not just to you.

It’s not something done to a person—it’s something shared with them.

Real safety is person-centred and trauma-informed. It offers power with, not power over. There is no ego in true safety. No hierarchy. No pretending. It’s authentic. It’s relational.

What Safety Is Not

Safety is not critical.

Safety is not harsh.

It does not shame, label, or undermine.

It does not view people as ‘disordered’ or broken.

It doesn’t see behaviour as a problem, but as communication.

Safety never seeks to dominate. It doesn’t come with a mask of professionalism that hides the truth. It doesn’t speak without listening, or diagnose without first understanding.

Embodied Safety & Neuroception

The nervous system is always asking: Am I safe?

This process happens beneath conscious thought. It’s called neuroception—the body’s way of detecting safety or danger without needing permission from the thinking brain. And it’s shaped by experience, trauma, culture, and relational patterns.

You might say all the right things, but if your nervous system is signalling fear, threat, or superiority—people will feel it. That’s why embodied safety matters more than spoken safety.

Embodied safety is felt in presence. In pace. In tone. In facial expression. In regulation.

Anchoring - How We Hold the Space

An anchor provides stability in a storm. In trauma recovery, we become anchors by being grounded ourselves. That’s why co-regulation is the first step—because two dysregulated people equal more dysregulation.

As practitioners, parents, or peer supporters, we must first ask:

Am I regulated? How do I know?

If we’re anxious, rushed, or emotionally reactive, it will be felt. No matter how well we hide it.

There is no safety in dysregulation. No matter the training, titles, or tools we carry.

Trauma Informed TRUST Our Framework for Safety

Healing requires TRuST:

- Trigger Recognition – Understanding what activates distress

- Reassurance – Calming the nervous system with presence and care

- Understanding – Listening with curiosity, not assumption

- Safety – Being reliably kind, consistent, and grounded

- Truth – Because without truth, there is no trust—and without trust, there is no safety

Truth doesn’t mean brutal honesty. It means kind truth, delivered with compassion and timing. It means not hiding behind language or roles. People need to know what’s real, not just what’s rehearsed.

The Person-Centred CUE

To guide this work, we return to the person-centred core conditions: CUE

- Congruence – Be genuine. Speak your truth with kindness. No masks.

- Unconditional Positive Regard – See the person, not the problem. Let them feel felt.

- Empathetic Understanding – Step into their world. Feel with, not for.

These are not just therapeutic ideals. They are safety signals.

For Practitioners - A Gentle Challenge

Before you ask someone to trust you, ask yourself:

- Am I regulated enough to offer safety?

- Can I sit with another’s pain without needing to fix or label it?

- Is my truth gentle and clean, not laced with judgment or superiority?

Safety isn’t created by accident. It’s cultivated by intention. And it begins within.

Real Safety Is a Felt Sense

Not a checklist. Not a branding. Not a buzzword.

Let’s stop mimicking safety and start embodying it. The nervous system can tell the difference. So can the heart.

For All the Wrong Reasons: Why Lived Experience Matters in Family Court

People don’t enter relationships with someone they know to be violent. That assumption – “Well, you chose him” – is ludicrous and cruel. It’s victim-blaming disguised as wisdom.

The truth is, perpetrators of violence and abuse don’t reveal their true selves at the start. What you meet is charm, attentiveness, someone who seems perfect – someone who makes you feel seen. By the time the mask slips, you’re already entangled. People talk about “red flags,” but often these aren’t visible early on – love, after all, is blind.

What we really need to talk about are the white flags: the subtle signs in ourselves – low self-worth, shaky boundaries, buried trauma – that leave us vulnerable to being targeted in the first place. Self-awareness and self-compassion are the true protectors. I didn’t know that then. I was 20, shy, naïve, gentle and unequipped for the storm that followed.

Three months in, he became violent. Not shouting, not slamming doors – extreme violence. The kind that leaves you in permanent survival mode. I lived that way for years – constantly scanning, adapting, walking on eggshells. Then one day, he tried to end my life.

I left. I left my home. I left my body.

That’s the only way I can describe it. I fell into what I now understand to be a dorsal vagal state – a trauma response where the nervous system shuts down. I wasn’t safe, so my body made me disappear. Numb, disconnected, leaking tears without sound or sensation – like my body was crying, but I wasn’t even there to feel it. I was living in a round, grey cell beneath the pavement cracks I’d always stared at when walking. No exits. No hope. No comprehension of joy.

That’s where I was the day I stood in Court One, supported by victim services, as he was found guilty and bound to keep the peace for 12 months. I was awarded £300 in compensation for the years of terror. He refused to pay. The courts told me it wasn’t worth pursuing. The message was loud and clear: my suffering had a price – and even that wasn’t worth collecting.

That afternoon – yes, the same day – I was summoned to Family Court. There, I was told I had to hand my children over at 4pm to the very man who had tried to kill me.

If you’re a parent, try to imagine that.

Try to imagine being forced to place your child in a cage with a wild animal – and being made to watch. That is what the family court system did to me. For two years, I endured a legal chess game designed to protect his “rights” as a father – not my children’s right to safety.

He was never interested in the children. This was about control, punishment, power. And the system let him play.

Eventually, his mask slipped in public. He physically assaulted the court welfare officer – the first professional to dare challenge him. He also took off with my youngest child, using fear like a weapon.

I had seen it coming. I felt it in the energy. I had lived with it for so long I could tell when his mood shifted – when the storm was about to break. I warned them. I tried to explain. I was dismissed, minimised, and ignored.

It took that – the assault of a professional – for the system to finally act. At the next hearing, I was praised, validated: “a kind and loving mother doing everything in her power to protect her children.” He was branded a violent man unfit for contact. Not even a letter. At last, the outcome we had needed all along.

But it came for all the wrong reasons.

Why did it take institutional harm to prove what lived experience had been screaming all along?

This is why lived experience matters. Because no theory, no policy, no textbook can replace the insight of someone who has lived through what you’re trying to understand. The family court system cannot afford to be deaf to those who have walked its halls in fear. Those who have watched their children be handed back to danger. Those who know that safety isn’t something you can always see on paper – but you can feel it in your bones.

I survived. But not because of the system. I survived in spite of it.

And I will keep speaking – not because it’s easy, but because it’s necessary. For all the women (and men) who are being failed today, and for all the children who need someone to see what’s really happening – before it’s too late.

The Dorsal Space: Where Suffering Lives – And Where We Can Begin Again

I’m not a neuroscientist. I don’t claim to have all the answers. But I know the dorsal space. I’ve lived there. I walk with others through it. And I believe it’s where the deepest suffering lives—quiet, hidden, and often misunderstood.

The Physiology of Giving Up

Can Dorsal States Lead to Violence?

Many schools are not yet equipped to support dysregulated children, especially those living in dorsal states. Behaviour is often viewed through a disciplinary lens, and connection-seeking is mislabelled as attention-seeking. It’s hard to understand the world from a dorsal perspective if you’ve lived your whole life in the safety of ventral. But for some children, ventral connection isn’t familiar—it feels foreign or even unsafe. Their behaviours aren’t manipulative; they’re adaptive. Without this understanding, children in shutdown are often misunderstood, punished, or ignored—deepening their isolation and reinforcing the belief that they do not matter.

The Power of Being Seen

Safety isn’t a concept. It’s a felt experience.

Final Thoughts

Through Different Eyes: How Our Nervous System Shapes Our Reality

What seems like an overreaction might be a nervous system doing its best to protect!

Same Room, Different Worlds

Two people.

One moment.

Entirely different experiences.

Have you ever been confused by how differently someone reacts to the same situation you just lived through?

One person shrugs it off. Another breaks down. You’re left wondering — how can it feel so different?

The answer isn’t in the moment itself, but in the lens we’re looking through — and that lens is shaped by the state of our nervous system.

The Nervous System as a Lens

The autonomic nervous system doesn’t just regulate heart rate or digestion — it shapes our entire perception of reality.

When we’re in a ventral vagal state (safe, connected, regulated), the world feels manageable. We can connect with others, think clearly, and respond rather than react.

But if we’re in a sympathetic state (fight/flight) or a dorsal vagal state (shutdown, collapse), everything is coloured by threat. A neutral face can feel hostile. A quiet pause can feel like rejection. Our body’s state becomes our story.

We don’t see things as they are — we see things as we are.

Survival Childhoods Without Obvious Trauma

Not all trauma is loud.

Sometimes it’s the silence that hurts.

You might have grown up in a home where your parents worked tirelessly to give you a better life — but were rarely emotionally available. Maybe you were loved, but not felt. Fed, but not seen.

These are survival environments, not neglectful in the traditional sense, but not consistently safe for emotional growth either.

- Homes where emotions were brushed off or shamed.

- Parents under chronic stress, doing their best but never fully present.

- Socioeconomic pressure where survival came before connection.

This shapes a child’s nervous system — not just their behaviour.

How Children Make Meaning

Children are brilliant at making sense of the world.

But when their caregivers are distracted, overworked, or emotionally unavailable, children don’t blame the adults — they blame themselves.

- “I’m too much.”

- “They’d stay if I were better.”

- “It’s safer to stay quiet.”

- “I can’t trust people to be there.”

These aren’t just thoughts — they become embodied beliefs, felt in the nervous system. And they colour every future interaction.

Same Situation, Different States

Let’s imagine a simple scenario:

Your boss gives you some constructive feedback.

If you’re in a ventral vagal state (safe and regulated), you might think:

“Okay, I can work on that. This is helpful.”

If you’re in a sympathetic state (anxious, hyper-alert):

“Oh no, I’ve messed up. What do they really think of me? Am I in trouble?”

If you’re in a dorsal vagal state (shut down, numb):

“What’s the point? I’m just not good enough. I should give up.”

Same words. Same moment. But three entirely different internal worlds.

We’re Not All Starting From the Same Place!

This is why judgment and comparison are so unhelpful.

One person may seem “resilient” while another is overwhelmed — not because one is stronger, but because their nervous systems are playing by different rules based on past experiences.

Some of us had the luxury of regulated caregivers.

Some of us grew up managing our own distress alone.

Regulation is not just a skill — it’s often a privilege we weren’t taught.

We’ve come to associate trauma with extremes: abuse, violence, disaster. But trauma is often more nuanced.

It’s the chronic absence of emotional safety.

It’s being told you’re lucky to have a roof over your head while your feelings go unseen.

It’s learning to hide your needs to avoid burdening already exhausted parents.

These subtleties shape our nervous system responses long before we can understand them — and they carry into adulthood in ways that can feel confusing and difficult to explain.

The Power of Awareness

When we begin to see our reactions through the lens of the nervous system, everything softens.

We can stop asking, “What’s wrong with me?”

And start asking, “What happened to my sense of safety?”

Questions to explore:

- What state am I in right now — safe, anxious, shut down?

- What is my body trying to protect me from?

- Is my response about this moment, or something deeper?

Compassion grows from understanding.

Healing begins with awareness.

In Closing - A Call for Compassion!

We are all walking around with invisible stories written by our nervous systems.

Next time someone reacts differently than you — or you feel frustrated with your own sensitivity — pause. Remember: we’re not all seeing the world through the same lens.

Be curious. Be kind. And above all, be gentle — especially with yourself.

Want to Explore More?

If this resonated with you, you might enjoy my free trauma-informed programs, nervous system workshops, and reflective tools for healing and connection.

Visit A Positive Start CIC

You’re not broken — your body just adapted to a world that wasn’t always safe.

And now, you get to relearn what safety feels.