Speechless

You know that feeling when a chunk of food gets stuck in your throat or when you swallow ice? When your tea is too hot. That throat infection you got as a kid when even juice hurt.

That’s how talking felt.

I didn’t speak for a while when I was a child. It wasn’t that I couldn’t physically, I didn’t know the words anymore, the pain was too sharp, it made my breathing erratic, hurt my eyes.

I could only speak when it was just me and my mum together or very trusted friends. With anyone else, when I was anywhere near my abusers or someone who could become that, or someone who could never be allowed to know; my throat shut down, my words jumbled and tightened until nothing made sense, my chest hurt. So in most environments I stopped speaking.

I remember being shocked that my speech therapist didn’t own a television. I was around 7 or 8 and I couldn’t comprehend how someone could survive without tv. That was the very first question I asked her. She spent the next few months showing me the real life tv right outside the door, the park, the riverside, walks through trees and along quiet roads. In time my throat relaxed and the words fell into place.

Years later during a period of repeating terrors, repeated assaults, continuous abuse in my youth and through adulthood I remember other times when the terror took my voice.

When I tried to scream,

but nothing came out.

When I wanted to shout but my throat tightened so much I could barely breathe.

When the words I could utter were either jumbled, broken or dancing between sentences and meanings.

When the words needed to be planned well in advance, scripted to distract people from the truth I truly wanted to say.

Experiences of physical abuse and violence, of exploitation, grooming, sexual abuse and rape.

Experiences of needing to hide that life from others including loved ones to keep myself and them safe.

Experiences of juggling lives to keep the truth camouflaged, using the words I could say to paint the picture people wanted to see.

Speaking hurt for a long time.

What I fear from letting myself cry to this day is the noise. I can’t scream.

Some days the words still get jumbled.

But they are my words now and I can say them. Without that pain, with lessening shame.

They are my words, spoken through choice, through purpose and with hope.

My voice was stolen for decades in different ways. Bit by bit I’m taking it back.

Through writing, speaking, drawing. Through gardening and letting myself cook meals to enjoy again, through feeling free to message, to chat, to go unscripted.

Through removing the performance and breathing in authenticity, my voice is coming back.

Through realising why I couldn’t talk or scream or cry, why I couldn’t explain anymore I have released the grip, the hold.

Through recognising who’s voices were feeding my thoughts I am taking back the control they stole.

Through reconnecting with myself and being gentle with the “numb” I am finding the words.

There is a way through the silence.

Behind The Façade

Behind the façade.

The words Boarding School conjure up different meanings depending on our exposure and experience.

For me it presents memories of abuse, mixed with thoughts of friends and fun. Adventures and pain, laughter and fear.

From high school to boarding school, home to dorm, mum to strangers, alone to never alone; a shift in environment and in the way I’d view the world.

People say children in boarding schools are privileged. That they are part of a separate group, elite, removed. I have heard the expectations of luxury and the jokes about what goes on after lights out.

What I have not heard so much about is the vulnerability of the children in these schools, in terms of a lack of trauma informed care, access for services, and environment-aware safeguarding.

What I have not heard is how many children from these schools are in the statistics for abuse and exploitation, as children or later as adults.

What I have not heard is survivors' voices being implemented into the design of school buildings and systems.

What I have not heard is how many of those wealthy circles protecting the schools are also in other circles protecting perpetrators, as they also know that no social worker is knocking on their door.

I would spend full terms in a building with other boarding children, day school children, boarding staff, day staff, teachers, cooks, and janitors, ministers, and governors, along with unknown visitors to the school; all without any family near by.

Weeks and months fully accessible to adults my family did not know.

I would hope that in the majority of cases this is not an issue, but in reality, a boarding school is the perfect opportunity for grooming and abuse. 24/7 access to children with no family to intervene.

I have read articles on the need for designated safeguarding officers, improved procedures and reporting, easier access for social care professionals in many environments yet boarding schools are rarely mentioned.

All children are vulnerable.

All children from assumed privileged backgrounds are vulnerable

All children from every economic class are vulnerable

Because they are children.

When a child is in the care of a school for their entire day and night for weeks and months at a time, extending to years; they are in the care of strangers. Their days are controlled by adults who may not always have good intentions. In an environment held separately by society.

Strangers provide their every activity, and those childrenmight not be returning home until the end of term or longer.

I know that children from the wealthiest families went through horrific experiences in these elite schools. I know that even at that age the children knew that no social worker was coming to save them, how could they when they don’t know we exist. No social work or police officers were going to knock on that school door or call their family. They were invisible.

There are gaps in the safeguards, the survivor led insights, the trauma awareness for these children.

There are assumptions made about why children are in these environments and a resulting determination of vulnerability.

Cheese and wine parties attended by local and unknown VIPs, chapel concerts attended by ministers and business people, sports days attended by their sponsors and anonymous staff do not equate to safety no matter the funding or image.

Corridors of beds with sleeping children fully accessible to adults does not equate to safety no matter the price.

Paid for education, uniforms, tuck boxes and name tags on clothes do not ensure protection.

I hope one day that the children in those schools are viewed as being as vulnerable as all children and are afforded the same level of protection with a built-in recognition of the importance of environment and the need for trauma awareness in all training, especially boarding staff. I hope the children and the systems surrounding them are made visible to all who aim to protect.

An Uncomfortable Truth

Women are capable and active in the sexual exploitation of children and adults, online, directly and within rings of abuse and grooming.

The recent coverage of Ghislaine Maxwell’s prison interview and more noticeably the responses to her words, highlights that people are often uncomfortable with this reality and will find reasons that they would notsearch for if it were a male in question.

The majority of reported and prosecuted perpetrators are male. This does not show the unreported and undisclosed incidents or involvement.

Child on child abuse reports are increasing. Male children being targeted by both sexes of adults is becoming increasingly discussed. Adults being groomed attracts comments of blame and justification, but the conversations are gradually happening.

As I untangled the web and rings of grooming and exploitation that surrounded me as a child and an adult, the existence of female perpetrators became clear and integral to the workings of the abuse.

Women are involved, directly, in the process of grooming and exploitation.

Women of various ages and backgrounds, or different financial status and community standing.

They are often the recruiters of victims, the identifiers of targets.

They are often the taxi service to transport children and adults to their abusers.

They are the mask of normality and safety for many perpetrators whilst being directly involved or enabling the abuse.

They are the teachers and care staff in boarding schools and care environments.

They are the secretaries and professionals with access to information on the targeted victims.

They are the bar staff, café staff, support workers, educators in every community.

They are the helpful neighbours and friendly locals.

They are the mothers and sisters of family and friends with the easiest of access.

They are the gentle suppliers of gifts and extra support for the victims, hiding their knowledge of the truth behind a loan of money or a ride home.

They are the babysitters, the local unofficial child minder.

They are presented as the safe contact online.

Denying this reality is dangerous.

Listening to our instincts about the women in our children’s lives is vital.

Getting curious about the actions of women who have unexplained access to your child, your friends, your family is vital.

Acknowledging the existence of female groomers and exploiters is necessary to protect victims and survivors.

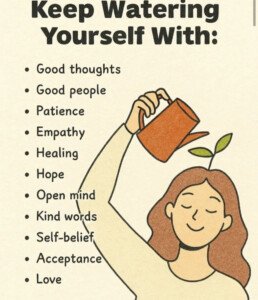

Hope

Encountering hope. Once, then, and now.

Over my lifetime hope has meant different things. The dreams and wishes I had as a child are returning, replacing, and reframing the wishes of many years.

I recently had a conversation about how to lead people to a place where hope feels both possible and safe. This led me to later look back at the aspirations I had and how they were shaped by both my environments and my connection to the world around me, also moulded by my disconnection from myself and from a safe space to dream.

Once

As a little child I hoped the world be like my story books, like the magical worlds I read about or that mum would tell me about at story time. Full of mystery and magic. I hoped for warmth, for giggles, for my favourite meals and sweets, for trips to my favourite places. Little wishes along with big hopes, mostly coming true. I felt safe with my mum and her family. I felt safe on dog walks by the river, days out by the beach, in our home.

Then

As a young child my hopes changed when safety was lost. The innocent dreams and wishes turned to dust as I saw the monsters come to life. My only wish was for it to stop. For the pain and confusion to go away, for them to go away. I could only look ahead in terms of days or a week, counting the sleeps until I would be back home and safe. Possibilities shrank and doors to escape were lost or locked. There were still glimpses of hope, family holidays far away from the threats, happy Christmases in hotels, time spent with safe people and loved pets. School reports congratulating my work, confirmations of my polite manners and gentleness. Mini adventures with friends in the village, down by the river or in our rooms playing the latest pop music.

As my childhood ended and adulthood crept in, my hopes shrank again, my trust of hope became more fragile. Throughout my teens until around 40 years of age, hope was a word I rarely heard and when I did it scared me. Disconnection from myself and from positive possibilities had set in during my childhood but my teenage and adult experiences compounded it. I had jobs, homes, relationships and family but I was also trapped in a world of exploitation, as a child and adult. Juggling lives erased hope bit by bit as there was no way of building safe or solid foundations. Hopeful situations became the threat as I tried to navigate my way through a web of deception, the events that could have built hope I viewed as bewildering and dangerous though thereal danger was all around me. My hopes were limited to that day, getting through, surviving the next 24 hours. Manoeuvring in a way that kept me hidden. Hoping no one would see me, hoping no one could see the reality behind the masks and roles I wore so well. Food, shelter, temporary visits to safety and comfort, paying the rent, props and supplies to keep me hidden. I’d once dreamt of being a journalist, or a writer. I’d once hoped for a quiet home where mum and family would have laughter and lightness, I’d once hoped for friendship without a cost. Abuse and exploitation, my survival instincts and responses, my need for connection, their need for control had turned hope into an impossible illusion.

Now

As I heal, bit by bit, hope is becoming a friend again. Small goals met, little wishes turning into reality, each time letting hope feel a bit safer.

Connection and trust opened the door to hope for me, let me see another possibility of being.

My hopes now are a mixture of big and small; all feel warm to me now instead of cold and unreachable.

From daily tasks losing their sense of pressure, to creativity taking root after a long, long time. From friendship being sensed and experienced as a trade off, a transaction, to the presence of authentic friends feeling happy and safe. Joyful.

Hope was something I had lost, given away, had stolen from me, like a treasure in those stories I read as a child. Trust and compassion gave me the treasure map as well as the belief that it was always mine to find. Truth and love for myself as well as others has given me the faith that this time I can hold hope, for ever.

This a space of being that many cannot reach, through no fault of their own. Hope is vital for us all, for every survivor. It’s a gift that we sometimes take for granted but one more valuable than I can explain. A gift we cannot simply give ourselves out of nowhere without a foundation, together protectors and safeguarding, survivors and advocates can build that foundation.

Comfortable visibility

This year has been a year of firsts for me. New experiences and challenges, new realisations. The most striking one just now is that it can be safe to be seen.

I have spent most of my life staying in the shadows and carefully monitoring my voice, checking that no one saw me and being cautious with my words. Living within a world of abuse and exploitation whilst juggling normality taught me, and others, how to stay invisible in order to stay safe.

It’s an expensive and dangerous trade off. It’s only now that I have the freedom and foundations to be seen that I realise what I lost.

Showing up, showing face, using my name instead of a nickname, putting myself out there is something I could never have done without genuinely person centred and trauma informed support. It’s something I could never have imagined myself doing until I found trust and hope, in others, in the wider world and in myself.

It still feels risky, my body still holds the voices and fears that were piled high over years. But day by day it’s become more comfortable. Each time I speak, write, remember in a safe way the danger moves further away, becomes quieter.

I don’t have to hide anymore. My silence helped me to survive in some ways, but it was never suggested in order to protect me. It was designed to shield the perpetrators and my fears were manipulated to convince me that silence and invisibility meant security.

I am finding my voice after a long time of fearing it. I’m learning methods to ease the pain and shame, to settle the nerves and be at ease connecting with others at the same time as connecting with myself.

I physically escaped that web, that world a decade ago. Now I’m escaping its ruins and remnants by allowing myself to be seen and heard in the hope that others are seen earlier. My key now is my voice, words and knowledge I hid for far too long.

There is a way through the maze of silence, a sustainable route based on truth, trust and hope. A path that opens up to and through purpose and safety.

Why Storytelling?

We talk to be heard.

We talk to convey and connect, to direct, resolve and understand. We talk through our stories, our experiences and insights. A shared human gift. Self expression with the aim of creating connection. To pass on opinions and ideas, to offer snippets of life in the hope of aiding another.

As a young child I was encouraged to read story books, to listen to fairy tales and children's classics. My mum and I would spend hours making up stories as we walked the dogs by the river. Creating adventures from our imagination, not realising at that age that my heroes came from within.

As I grew up, television took over. Watching other people's lives, finding reflections of my own. Songs told tales, soap operas said what we couldn't.

In adulthood the spaces to hear stories, to tell my own shrank. There are gaps in communities where stories are missed, unseen and unheard. Assumptions are made about our stories, expectations layered over our words. Labels attached, judgements made. These unheard stories are the glue that binds. They have the power to humanise and empathise. The power to shine a light on shared truths and to combat division.

When people feel silenced or overlooked they put their stories away, lock them up. When people feel their voices are unimportant or irrelevant they learn to stay quiet. Missing out on the truths around them and the potential of others understanding.

Connection through telling our stories benefits more than the narrator. The listener gains skills, shares purpose, holds space. The teller gains presence, a voice, compassion and recognition. This energy, the skills developed and the shared humanity inevitably spreads to the wider community, friends, colleagues, family, neighbours. The world opens up especially for those who could not access it before.

I recently told my story to a small audience, at the age of 51. For the first time I stood up and spoke my truth, my experience to friends and strangers. This taught me a lot and opened doors I didn't expect.

I held space for myself and my listeners and they held space for me. I fought and overcame anxiety, the nerves. I learned how to pace, how to connect through words and truth. I learned to trust myself and to trust others with my stories. I felt part of something bigger, something honest and open. I felt hope. Hope for shared humanity, shared experiences, echoes of each others' stories.

Have a voice is fundamental for self freedom and development. Uniting voices is essential in forming strong communities through shared truths and perspectives.

I picture a space where the previously voiceless can talk, safely and authentically. A comfortable environment, senses recognised and supported. Fellow storytellers sharing time and holding space. Connections formed with themselves and the community around them.

All types of stories about lives, hopes, the local area, news and views. Happy tales, sad ones, heartfelt and light fun. Relating to each other through stories and expression. Talking, writing, creating, art and prose, listening.

Empowering individuals and the community.