When we talk about trauma, we often speak of fight or flight—but rarely of the quietest survival state of all: freeze or collapse.

Yet it’s this state—the dorsal vagal response—that I know most intimately.

After the attempt on my life, when I lost consciousness through strangulation, my body did something remarkable: it protected me the only way it could.

It shut down.

I now understand that moment—and the long, ghost-like months that followed—as dorsal collapse, a state where the nervous system withdraws energy to survive what feels utterly inescapable.

The Three States of the Nervous System

Polyvagal Theory, developed by Dr Stephen Porges, helps us understand how the body organises itself around safety and danger through three main pathways of the autonomic nervous system, each linked to the vagus nerve—the body’s longest cranial nerve connecting brain to body.

- Ventral Vagal — Safety and Connection

When the ventral vagal system is active, we feel open, present, and connected. Our voice softens, our digestion works, and we can think clearly. This is the state where social engagement and healing happen. - Sympathetic — Mobilisation

When we perceive threat, the sympathetic system energises us to fight or flee. Our heart rate increases, adrenaline flows, and we move into survival action. - Dorsal Vagal — Immobilisation and Collapse

When neither fight nor flight can help, the body shifts into the oldest survival strategy—shutdown. Breathing slows, energy drops, awareness fades. It’s the body’s last effort to preserve life by numbing pain and conserving resources.

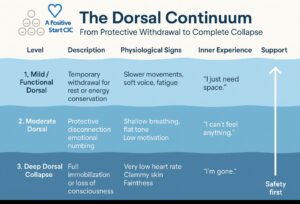

There Are Levels to Dorsal Collapse

Not all shutdown looks the same. Think of dorsal as a continuum—like sinking below the water’s surface. The depth we reach depends on history, context, resilience, co-regulation, and whether the body senses escape or safety.

1 | Mild / Functional Dorsal — Protective Withdrawal

- In real life: going quiet in a meeting, zoning out, needing to lie down after stress, skipping social plans from sheer flatness.

- Common triggers: overstimulation, subtle exclusion, relational disappointment, post-burnout “crash.”

- Body feel: heavy limbs, soft/low voice, shallow breath, “I just can’t right now.”

- Support: warmth, hydration, orienting (notice colours, shapes), light rhythmic movement, permission to rest without shame.

2 | Moderate Dorsal — Numbing and Disconnection

- In real life: emotional blankness after pain (“I know I should be upset but I feel nothing”), losing time, glass-wall feeling.

- Common triggers: chronic invalidation, powerlessness, coercive dynamics, medical procedures.

- Body feel: hypoarousal (cooling, slowed heart rate), dissociation, fog, “Nothing matters.”

- Support: sensation-based grounding (texture, warmth), co-regulation, gentle voice engagement, micro-movement breaks.

3 | Deep Dorsal Collapse — Complete Shutdown

- In real life: freezing mute, curling up, fainting/collapse, out-of-body detachment.

- Common triggers: life-threatening violence, choking/strangulation, witnessing severe trauma.

- Body feel: steep drop in heart rate and blood pressure, clammy skin, irregular breath, possible loss of consciousness.

- Support: safety first—quiet, warmth, steady presence. Mobilise only once the body feels safe enough to rise.

The deeper the collapse, the more energy and safety the body needs to rise again. Healing isn’t forced; it’s coaxed.

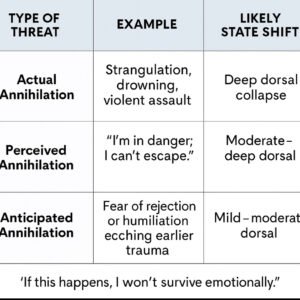

Actual vs Perceived Annihilation

Our nervous systems run on neuroception—a pre-conscious scanning for safety or threat. It doesn’t wait for evidence. That’s why a perceived annihilation (“I can’t breathe”) can evoke the same shutdown sequence as an actual threat to life.

During a panic attack, oxygen is available but the body’s felt sense says “I’m suffocating.”

Hyperventilation lowers carbon dioxide, causing dizziness and tight chest sensations; the brain reads this as life-threatening and may swing from sympathetic overdrive into dorsal shutdown (faint, numb, collapse).

From Dorsal to Sympathetic: Moving Away from the Edge

When someone is in deep dorsal, the first step isn’t positivity or logic—it’s mobilisation.

Tiny increments of movement or breath invite the body back toward agency: standing, orienting, swaying, humming, walking, or sighing. Once energy returns, ventral safety—connection, calm, trust—becomes reachable again.

Recognising “Nearly Crisis”

Even a mild dorsal state can drift into depression and suicidal ideation. Early recognition saves lives.

Watch for:

- Sudden flatness after stress or conflict

- Withdrawal from supportive routines

- Slowed movement, soft monotone voice

- “I feel far away / not really here”

- Cold or clammy skin, shallow breathing

When you see this: lower demands, increase safety.

Soften tone, shorten expectations, offer warmth, grounding, and co-regulation before talking solutions.

What Recent Neuroscience Is Showing

- Vagal flexibility: Low heart-rate variability (HRV)—less flexible vagal tone—is consistently linked with depression, trauma load, and suicidality risk.

- Brain networks: Chronic threat alters connectivity between the amygdala (fear), insula (body awareness), and prefrontal cortex (control), shaping how quickly we tip into defence and how slowly we return.

- Breath and CO₂: Controlled slow breathing and humming raise CO₂ slightly, calming panic and restoring vagal balance.

- Emerging interventions: Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation, rhythmic movement, music, and vocal exercises show early promise for regulation.

- State before story: Regulation precedes reasoning; once we help the body move between states safely, perspective and problem-solving follow.

What We Don’t Yet Know

- Causality: Research hasn’t yet proven that deliberately shifting dorsal → sympathetic directly reduces suicidal ideation, though clinical experience suggests benefit.

- Measurement limits: HRV is a window, not the whole landscape, of vagal activity.

- Human variation: People blend states—numb yet anxious, still yet tense. History, culture, neurodiversity, and medication alter the picture.

- Anatomy debates: Some Polyvagal details remain contested, yet its framework continues to help us understand lived experience.

- Dosing mobilisation: The “how much, how fast” question still needs empirical study.

Integrating Lived Experience and Research

What I’ve shared brings together lived experience and current neuroscience—reflections formed through both personal recovery and professional practice.

These insights are not medical directives, but an evolving theory-in-practice: an attempt to bridge what the science tells us about the nervous system with what the body teaches through survival and healing.

Polyvagal understanding, when grounded in compassion, becomes relational rather than theoretical—a way of noticing, naming, and nurturing safety in ourselves and others.

Closing Reflection: From Despair to Connection

Understanding the nervous system through a Polyvagal lens helps us spot “nearly crisis” sooner, before despair deepens into collapse. When we recognise the early drift into dorsal, we can respond with gentleness—less demand, more safety, warmth, rhythm, and presence.

Sometimes the bravest thing a body ever did was shut down.

Our work is to honour that wisdom—and gently guide it back to safety.

If You or Someone You Know Is Struggling (UK)

If risk feels immediate, call 999 or go to A&E.

For urgent support: Samaritans 116 123 (free, 24 / 7) or text SHOUT 85258.

You are not alone. There is a way back.

Disclaimer

This article and its visuals reflect my lived experience, professional reflections, and personal interpretation of current trauma and neuroscience research.

They are intended to encourage understanding and dialogue—not to provide medical or scientific advice.

Each person’s nervous system is unique, and anyone experiencing distress or suicidal thoughts should seek appropriate professional and emergency support.

Infographic: The Dorsal Continuum — From Protective Withdrawal to Complete Collapse © A Positive Start CIC created using Ai.