Seeing the Person, Not the Problem

It’s been a tough week.

A week of study and learning.

My own MSc reading.

Supporting others with theirs.

Noticing how theory is learned… & then how it translates into real lives.

Later in the week, I read case studies, medical & session notes from across clinical professions — GPs, counsellors, psychiatrists, psychotherapists, students, to consultants.

I felt sadness.

Not because theory was absent — it wasn’t.

Carl Rogers was cited.

The person-centred approach was named.

The language of practice was present.

But something essential was often missing.

When all that is seen is behaviour & “presenting problems”, the human beneath can remain unseen & unheard.

Across different disciplines, I noticed patterns — adaptations being labelled, survival responses being pathologised, & meaning being assigned without fully understanding the lived experience beneath the behaviour.

I read how ambition in someone living in very difficult circumstances was described as delusional — even grandiose.

And I wondered… when did hope become pathology?

From a lived-experience & trauma-informed perspective, I see something different.

I see survival.

I see adaptation.

I see nervous systems shaped by what has happened, not who someone is.

As trauma research continues to show — including the work of Bessel van der Kolk — behaviour often reflects stored experience, not personal defect.

And I return, again and again, to Rogers’ core conditions:

• Congruence

• Unconditional Positive Regard

• Empathic Understanding

These are not simply concepts to reference.

They are ways of being with another human.

If we truly hold unconditional positive regard, we do not reduce a person to their current circumstances.

If we practice empathic understanding, we ask:

What has happened to you?

Not:

What is wrong with you?

Neuroplasticity tells us change is possible.

Trauma recovery research tells us safety, hope, & relational presence support healing.

Hope is not delusion — it is often the first sign that someone still believes life could be different.

It’s been a tough week for humanity.

And especially for victims & survivors of abuse.

Because when a survivor dares to imagine a different future & that hope is reframed as pathology, we risk repeating the silencing they have already lived through.

We can do better.

In our teaching.

In our supervision.

In our practice.

We must teach students & practitioners not only to recognise problems — but to see people.

To look beneath behaviour.

To understand adaptation.

To honour hope.

To remember that sometimes what appears “grandiose” is simply a human being who has survived — and still dares to dream.

The human must always come before the label.

Always.

Supporting Nervous System Regulation During Trauma Work:

Learning to care for the helper as well as the person being helped

Working with trauma survivors is deeply meaningful, but it can also touch the helper’s nervous system in powerful ways. Regulation is not something we arrive with fully formed — it is a practice we learn over time, often through experience, reflection, and self-understanding.

In my early days of this work, I remember coming home after listening to a survivor’s story of abuse and feeling utterly depleted. There was a heavy dread in my body and head that I could not shift. My mind kept returning to the injustice and the horror of what they had endured. I found myself imagining what if that had been me. The weight of it made me physically and emotionally unwell. I cried over the following days and even questioned whether I was the right person for this work.

As tends to be the case for me, I learned the hard way. I became curious about why I had been impacted so deeply. What had happened to them was undeniably horrific — but it was not my trauma, so why did I feel so broken by it?

This question led me to research the nervous system, vicarious trauma, and emotional regulation. Dan Siegel covers it in his Interpersonal Neurobiology (IPNB) course, which I highly recommend for anyone working with trauma survivors. Over time, I developed ways to protect my nervous system without disconnecting from the human suffering in front of me — and without losing the empathy and care that matter so much in this work.

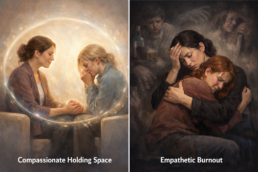

One of the most important shifts I made was choosing compassion over emotional absorption.

Empathy allows us to feel with another person — but when unregulated, it can place us in their shoes. The body can begin to respond as though the experience is happening to us. Over time, this can lead to emotional exhaustion, heaviness, and burnout.

Compassion is different.

Compassion allows us to remain present with another human being in their pain without becoming engulfed by it. We witness, we care, we support — but we remain anchored in ourselves. Compassion says: I see your suffering, and I am here with you, rather than I am inside your suffering. This subtle shift protects the nervous system while preserving genuine human connection.

Through practice, I also learned that when we listen to trauma, our attention can narrow and the body can move into a quiet survival response — tightening, bracing, holding. If we do not notice and gently regulate, we can begin to carry what we hear. Broadening awareness, orienting to the present, and reconnecting with the body help restore balance and remind the nervous system that we are safe, here, now.

Regulation is not about becoming unaffected. It is about developing the capacity to stay steady, present, and compassionate — without being pulled into the depth of another’s trauma.

If you are beginning this work and find yourself feeling heavy, tired, or emotionally stirred, please know: this does not mean you are unsuited to the work. It means you are human. With time, awareness, and gentle practice, you can learn to care for your nervous system as you care for others.

Compassion with regulation sustains the helper.

And sustained helpers can continue to walk alongside those who need them most.

Why Regulation Matters

When we listen to trauma stories, our attention can narrow and the nervous system may move into a subtle survival state (tightening, vigilance, emotional contraction). Over time, this can contribute to vicarious trauma or emotional depletion.

Broadening awareness helps the nervous system recognise present-moment safety, allowing the body to soften and return to balance. This supports:

Emotional steadiness

Clear thinking and presence

Compassion without absorption

Reduced accumulation of stress

Protection against vicarious trauma

These exercises are not about “switching off” empathy. They help us stay connected without becoming overwhelmed.

Simple Regulation Practices

You may wish to use these between sessions, after difficult work, or whenever you notice tension building.

1. Broadening Awareness (Open Focus)

Gently widen your attention beyond one point of focus.

Notice your body sitting

Become aware of the space around you

Notice sounds in the room or distance

Allow your gaze and attention to soften

Remind yourself: “I am here, and this moment is safe.”

This helps release nervous system contraction and restore ease.

2. The Wheel of Awareness (Dr. Dan Siegel)

This guided practice gently moves attention through:

The senses

The body

The mind

Awareness itself

It supports integration, grounding, and returning to the observing self rather than becoming absorbed in emotional material.

Link to Guided Meditation Video

3. “In Space” Awareness Morning Meditation (Dr. Joe Dispenza / Open Focus style)

Instead of concentrating on sensations, allow awareness to include space and openness.

Notice sensations in the body

Then notice the space around the body

Let attention expand rather than focus narrowly

Allow thoughts and sensations to exist without holding them tightly

This often reduces emotional load and restores calm.

Link to Guided Meditation Video

4. Orienting Back to Self (Quick Reset)

After emotionally intense work:

Feel your feet on the ground

Notice your breath

Feel the weight of your body in the chair

Look around the room slowly

Remind yourself: “I am here, now.”

This helps the nervous system separate yourself from the material you have heard.

Gentle Reminder

Regulation is not about doing it perfectly.

It is about noticing, returning, and caring for your nervous system as you care for others.

Compassion with regulation protects both the helper and the person being supported.

Take good care of yourselves

Debs x

Is It Possible There Can Be Two Selves?

I was recently asked a question that landed quietly but powerfully:

“Is it possible there can be two selves?”

My answer came without hesitation:

“Absolutely.”

What follows is not theory offered from a distance, but reflection shaped through lived experience, me search, we search, research — alongside trauma-informed understanding and spiritual insight. This is not something I have only studied; it is something my own nervous system lived through, and did what it needed to do to protect life when life was under threat.

Because depending on where you stand — psychology, spirituality, trauma, neuroscience, lived experience — the idea of “two selves” is not strange at all. In fact, it is deeply human.

The Simple View: The Thinker and the Observer

At the most basic level, many of us recognise this:

There is the voice in our head that worries, plans, criticises, imagines.

And there is the part of us that notices that voice.

As Eckhart Tolle writes in A New Earth:

“What a liberation to realize that the ‘voice in my head’ is not who I am. Who am I then? The one who sees that.”

— Eckhart Tolle

Eckhart Tolle describes this beautifully in A New Earth. He speaks of the difference between:

- The chattering ego-mind

- And the observer, the part that watches the thoughts without becoming them

The moment you notice “I’m stuck in a loop of anxious thinking”, you are no longer just the thinker — you are also the one who sees the thinking.

As Tolle also teaches:

“The moment you realize you are not present, you are present. Whenever you are able to observe your mind, you are no longer trapped in it.”

— Eckhart Tolle

That alone already suggests more than one self at play:

- The one who experiences

- And the one who observes

Internal Family Systems: The Inner Child, the Protector, and the Self

From an Internal Family Systems (IFS) perspective, developed by Dr. Richard Schwartz, the idea of “two selves” expands into something even richer. IFS does not see us as one fixed identity, but as a system of parts, all organised around survival, protection, and the longing for safety.

In this model:

- The inner child is often understood as an exile — a part that once felt terrified, helpless, unseen, or unsafe and now carries that original fear, pain, or shame.

- The protectors are the parts that stepped in to manage threat, danger, and overwhelming emotion when that child part had no other way to survive.

- And beneath it all is the core Self — the calm, compassionate, grounded presence that Dr. Schwartz describes as the natural leader of the internal system when enough safety is present.

Schwartz’s work is grounded in decades of clinical practice and shows that these parts are not signs of pathology, but signs of adaptation and intelligence. Exiles are not frozen because something is wrong with a person — they are held because the nervous system once learned that full awareness of their pain was too much to carry alone. Protectors are not problems to eliminate — they are guardians that formed with one purpose: to keep the system alive.

When someone says,

“Part of me is scared, and part of me knows I’m safe now,”

they are describing this internal system in action — the exile and the Self, with protectors often standing quietly in between.

The parts that step in to manage life, danger, and emotion are known as protectors. Some protect by staying hyper-alert, controlling, pleasing, rescuing, or fighting. Others protect by pulling awareness away — through numbness, withdrawal, dissociation, or watching from a distance.

From this perspective, the part of me that went inside and looked out at the world can be understood as a protector creating distance to shield the exile from further harm. And the inner voice that later summoned me back into full presence when it was time to protect my children was also a protector — not a different self, but the same survival intelligence responding to a changing level of threat.

None of these parts are bad.

None are broken.

Each formed in service of survival.

Trauma, Splitting, and the Two Selves of Survival

From a trauma-informed lens, the experience of “two selves” often begins in childhood.

When a child faces:

- Overwhelming fear

- Violence

- Emotional abandonment

- Or situations they cannot escape

the nervous system must adapt.

If fight and flight are not possible, the system may:

- Freeze

- Or dissociate

This is where splitting of awareness can occur:

- The inner child remains frozen in terror

- A watching self steps back to survive

- A protector takes over to keep life functioning

This is not breakdown.

This is adaptation under unbearable conditions.

Watching the World From a Safe Place Inside My Mind

For me, this wasn’t a theory. It was lived reality.

In the days that followed the violent attack, I was withdrawn and not functioning properly. I was inside myself, but behind something — observing others from a distance yet unable to engage. It felt as though I was inside the screen of a television set, looking out at the world, rather than standing in it.

I was numb.

And I was content to stay there — because it felt safe. It felt like an actual place inside my mind where nothing could reach me. Life was happening out there, and I was protected in here.

From a trauma lens, this is shock and dissociation.

From a human lens, it felt like sanctuary.

Then something else happened.

Another part of me raised its voice.

It told me it was time to return.

It reminded me that I had children.

That I had responsibilities.

That I needed to wake up again — not just for myself, but to protect them and to protect myself from the consequences of other people’s decisions.

I wrote about this in my book When I’m Gone.

People sometimes imagine this state as temporary madness.

I see it as brilliant ancient wisdom.

My parents, doing what they believed was right, took me to the GP. The doctor spoke about me to my parents — not to me. He recognised that I was legally an adult, but also that I was not fully present. He named shock. His professional opinion was Prozac.

And then that same inner voice — the one that rose not only in my mind but echoed through my whole body — protested.

It warned me not to take anything.

It summoned me to wake up.

To get up.

To stay alert.

It told me, very clearly:

“You will not survive if you are not awake and aware.”

And it was right.

Only days later, my attacker broke into my home with a lump hammer.

If I hadn’t been fully functioning — if I had still been sealed behind that inner screen — I may not be here today. That is my belief.

This inner voice is not new to me.

It is the same voice that:

- Kept me going when I was running the 400 metres at school

- Guided me through a crowd of young people who were teasing me

- Reasoned and steadied me during interviews and moments of pressure

It is my internal ally — the part of me that has been with me for as long as I can remember. The part that keeps my inner critic in check. The part that knows when to hide — and when to rise.

From a trauma perspective, this is the protector activating.

From a nervous system perspective, this is survival mobilisation.

From a spiritual perspective, this is inner guidance.

From my lived experience, it is all of these at once.

The Nervous System Was Not Broken — It Was Brilliant

In trauma-informed language:

- My ventral vagal system (safety and connection) was offline

- My system shifted between:

- Sympathetic survival (hypervigilance)

- Dorsal vagal shutdown (numbness, dissociation)

- The inner child was overwhelmed

- The observer and protector stepped in

This is not something going wrong.

This is the body saying:

“I will keep you alive, even if I have to split awareness to do it.”

The Spiritual Perspective: The Witness That Never Left

Across spiritual traditions, the witness consciousness appears again and again

As Eckhart Tolle reminds us:

“The mind is a superb instrument if used rightly. Used wrongly, however, it becomes very destructive.”

— Eckhart Tolle

- The soul watching the human experience

- The higher Self guiding the frightened parts

- The inner presence that remains intact even when the outer world collapses

Even when we:

- Speak to ourselves in our head

- Pray for guidance

- Ask internally for strength

we are already in dialogue between selves — often between a frightened inner child and something wiser, steadier, and more loving.

A Metaphysical View: Consciousness Beyond the Body

From a metaphysical perspective, the idea of “two selves” is not unusual at all. In fact, many metaphysical traditions suggest that consciousness itself is not confined to the physical body or brain, but uses the body as a vehicle for experience.

In this view, there is:

- The human self — shaped by memory, emotion, trauma, learning, and survival

- And the conscious awareness that witnesses that human experience

This awareness is not created by fear or trauma — it pre-exists it.

From this lens, when I describe being:

- Inside the screen, looking out at the world

- Watching life happen from a protected internal place

That can be understood not only as a nervous-system response, but as consciousness withdrawing its full immersion from physical experience when the experience becomes overwhelming.

Not as escape — but as preservation.

Metaphysics does not see this as “disorder.”

It sees it as conscious intelligence responding to threat.

From trauma science, the observer can be understood as:

- A protector

- A dissociative response

- A survival adaptation

From metaphysics, the observer is also:

- The seat of awareness

- The witness to experience

- The part of us that is not broken by what happens

This helps explain something many people notice intuitively:

Even when the body is frozen…

Even when the child is terrified…

Even when the protector is exhausted…

There is still something inside that knows.

Knows danger.

Knows timing.

Knows when to hide.

And knows when to rise.

This is exactly the voice I described — the one that summoned me back when it was time to protect my children and myself. Trauma-informed language calls that a protector. Metaphysical language calls it inner intelligence or conscious awareness. I hold room for both.

Metaphysics helps bridge a question many people quietly carry:

“If part of me was so terrified…

And part of me was watching…

And part of me was guiding…

Then who am I really?”

From a metaphysical lens, the answer can be:

You are the awareness that has held all of it.

- The inner child experienced

- The protector mobilised

- The observer watched

- But consciousness remained intact throughout

This does not diminish the reality of trauma.

It reframes identity so a person is not defined solely by what happened to them.

I don’t see trauma science and metaphysics as opposing forces. I see them as two languages describing the same protective intelligence.

- Neuroscience says: The nervous system adapts to survive.

- Metaphysics says: Consciousness withdraws to preserve itself.

Both are describing the same act of protection, from different angles.

One speaks in biology.

The other speaks in awareness.

Neither says the person is broken.

This matters because when people only receive a medical or diagnostic explanation, they may walk away believing:

- Their mind failed them

- Their system malfunctioned

- Their dissociation was a defect

Metaphysics adds another truth:

Something within you was wise enough to protect your life when life was under threat.

That matters.

It restores dignity.

It restores meaning.

It restores agency.

Why I Do Not See This as Disorder

Here is where I hold a clear personal truth:

We have taken natural human survival responses and labelled them as:

- Maladaptive

- Faulty

- Disordered

But what if:

- The terrified inner child disappeared in order to survive?

- The observer stepped back to prevent collapse?

- The protector mobilised to keep life going?

To frame these responses as inherently “wrong” is, in my view, deeply harmful to humans.

The nervous system did not betray us.

It saved us.

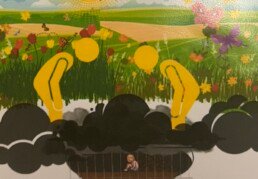

Integration: When the Adult Self Goes Back for the Child

Healing is not about erasing the observer or silencing the protector.

Healing is about building enough safety in the present so the adult Self can gently return to the child who once had to hide.

Over time, with:

- Regulation

- Compassion

- Choice

- Relationship

the inner child no longer has to live behind the screen.

The protector no longer has to live on red alert.

And the observer no longer has to stand watch alone.

A Gentle, Hopeful Truth

Yes — there can be two selves.

There can be many.

And none of them are wrong.

There is:

- The terrified child

- The protector

- The observer

- And the Self that can now hold them all

They were never signs of brokenness.

They were signs of a system that refused to let life end.

And when safety returns, something beautiful happens:

The child no longer has to freeze.

The observer no longer has to hide.

The protector can finally rest.

And the self — slowly, gently — begins to feel whole again.

When “Discipline” Becomes Harm: Understanding Cruelty Disguised as Parenting

When “Discipline” Becomes Harm: Understanding Cruelty Disguised as Parenting

There is a kind of harm in childhood that many people never talk about.

It doesn’t leave bruises.

It doesn’t always involve shouting.

Often, it was normalised.

And one of the main reasons people stay silent is simple:

Many don’t want to hurt the ones they love.

They protect others from the truth, even when those truths shaped their entire childhood.

This blog is not about exposing individuals or assigning blame.

It’s about naming the patterns that were common in certain generations — patterns many adults now look back on and quietly carry alone.

By talking about the behaviours rather than the people, we create space for understanding, accountability, and breaking generational cycles.

This is a conversation about what happened, not who did it or what contributed to the why - because countless families shared these dynamics behind closed doors.

The Hidden Forms of Cruelty Many Children Experienced

The “Seen and Not Heard” Era

A whole generation was raised with the belief that children were:

- to be quiet

- to stay out of the way

- to do as they were told

- to absorb adult tension

- to perform chores, not emotions

- to expect little, ask for nothing, and need even less

Love was inconsistent.

Warmth depended on mood.

And emotional expression was often treated as defiance.

Behind closed doors, many children became:

- emotional shock absorbers

- scapegoats

- housemaids

- the regulators of adult distress

Meanwhile, the same adults often presented as kind, helpful, charming, or community-minded in public.

This dual identity — tender outside, volatile or dismissive inside — left many children confused, unseen, and unheard.

Behaviours That Often Went Unrecognised as Harm

Saying “yes,” then denying it and humiliating the child

A child is told they can visit a friend, only for the adult to later insist they “never said that.”

The child is labelled a liar in front of others, left embarrassed and confused.

This is gaslighting, even if unintentional.

Setting children up to fail

Some adults created “tests” that were designed to expose, not teach:

- marking drinks to check if a child had sipped

- adding food colouring to sweets

- leaving temptation out deliberately

When the child behaved like a child, they were punished or shamed.

These tactics teach secrecy and shame — not honesty.

Spiritual or moral intimidation

Statements like:

- “God is watching.”

- “You’ll go to hell.”

- “The angels are disappointed in you.”

These may sound harmless to adults, but to a child, they are terrifying.

Children take every word literally.

Belittling, mocking, or ignoring the child

Children internalise words such as:

- stupid

- ugly

- lazy

- liar

- unwanted

Sometimes no words were spoken at all — they were ignored, which can be equally damaging.

Discrediting People the Child Loves & Weaponising Comparisons

Another subtle but deeply damaging behaviour is when adults discredit, insult, or undermine the people a child loves or looks up to.

This often sounds like:

- “You’re just like your dad.”

- “You’re turning into your mother.”

- “You’re exactly like that side of the family.”

…and then the adult immediately badmouths or criticises the person they’ve compared the child to.

To the child, this is more than just an insult. It becomes:

- an attack on their identity

- a rejection of half of who they are

- a warning not to love or resemble someone important to them

- emotional triangulation

- psychological splitting: “good side” vs “bad side”

Children absorb the message:

- “Part of me is unacceptable.”

- “Loving this person is wrong.”

- “I have inherited something flawed.”

- “I will be treated differently depending on who I’m compared to.”

This dynamic also forces the child to carry emotional loyalty conflicts they never asked for.

And when adults insult someone a child loves — especially a parent, grandparent, or sibling — the child feels:

- torn

- confused

- defensive

- guilty

- responsible for mediating tension

This is not discipline, and it is not parenting.

It is emotional manipulation disguised as comparison.

Adults Finding a Child’s Fear or Distress “Funny”

Another common but rarely acknowledged behaviour is adults enjoying a child’s distress — finding their fear, shock, or upset reaction humorous or “cute.”

This often looked like:

- teasing a child until they cried

- pretending something frightening was happening

- taking pleasure in the child’s startled facial expression

- laughing at a child’s trembling lip, fear, or confusion

- provoking an emotional reaction purely for amusement

At first, adults framed it as:

- “funny”

- “harmless”

- “cute”

- “just a joke”

But when the child became too distressed or overwhelmed, the adult often switched to irritation or blame, labelling the child as:

- “mardy”

- “over-sensitive”

- “dramatic”

- “spoilt”

- “in need of a lesson”

This pattern teaches the child:

- my emotions are entertainment

- my fear is amusing to others

- my hurt doesn’t matter until it inconveniences someone

- I am responsible for managing adults’ reactions to the pain they caused

The truth is simple:

It is not funny to enjoy a child’s fear.

It is not cute to provoke distress.

It is cruelty framed as humour.

And many adults still fail to recognise it for what it was — emotional harm disguised as “play.”

We see these same dynamics in workplaces today — the nervous-system triggers, the power imbalances, the “jokes,” the minimising, the discomfort used as entertainment. It’s bullying by any other name.

When a Child’s Distress Becomes Entertainment

Another overlooked form of emotional harm is when adults treat a child’s distress as entertainment.

This can look like:

- continuing to tickle a child long after they say “stop,”

until they cry, panic, or even lose bladder control - laughing when the child becomes overwhelmed or frightened

- mocking a child for showing emotion during a TV show, film, or advert

(“You’re getting upset over that?” “Oh, look who’s crying again!”)

Adults often insist it is:

- harmless fun

- just play

- funny

- cute

- “kids being dramatic”

But for the child:

- their “stop” is ignored

- their body boundaries are violated

- their emotions are dismissed

- their fear or overwhelm becomes a joke

- their vulnerability becomes a performance

The message the child absorbs is:

- “My limits don’t matter.”

- “My distress is amusing.”

- “I will be mocked for my emotions.”

- “People laugh at me when I’m overwhelmed.”

Tickling is especially confusing, because the body laughs even when the mind is in panic — and many adults use that as permission to continue.

Mocking emotional reactions to TV or stories teaches a child that emotion is shameful and empathy is something to hide.

This is not sensitivity — it is a child being emotionally exposed instead of emotionally protected.

Public humiliation & body/sexual “jokes”

Many children experienced humiliation in front of peers — sometimes involving sexualised or body-shaming “jokes” about their developing bodies. These incidents left deep embarrassment and confusion.

When an adult comments on a child’s changing body, weight, puberty, or clothing in a mocking or sexual way, it violates their sense of safety and dignity.

The child learns:

- “My body is something to be mocked.”

- “Adults can use my embarrassment for entertainment.”

- “My changes are not safe from scrutiny.”

This wound often lasts decades, affecting confidence, boundaries, and body image.

Shaking or physically overwhelming the child

Shaking may not leave bruises, but it creates profound fear. A child learns they are physically unsafe in the presence of adult anger or loss of control.

Their nervous system records the experience as threat, not discipline.

Withholding freedom after false promises

“Do your chores and then you can go out.”

But once the work is done, the adult denies ever making the agreement.

This teaches the child that fairness doesn’t exist and adults can’t be trusted.

Children are often blamed for things that had nothing to do with them:

- “I’m late because she wouldn’t get ready.”

- “He stressed me out this morning.”

This scapegoating teaches the child they are responsible for adult moods, mistakes, and choices — something no child should carry.

Publicly labelling the child

Children were sometimes described as liars, thieves, or troublemakers — often based on situations engineered against them or misunderstandings never repaired.

These labels become lifelong identities.

Blaming the child for adult arguments or unhappiness

Statements like:

- “We never argued until you came along.”

- “You’re the reason we’re unhappy.”

- “If you behaved better, everything would be fine.”

These messages teach a child to internalise adult conflict as their fault.

It shapes deep patterns of guilt, people-pleasing, and chronic responsibility.

Withholding essentials

Denying sanitary products, toiletries, or other basic needs is not discipline.

It’s a deep violation of safety and dignity.

Denying illness or pain

Many adults from previous generations dismissed illness as:

- attention-seeking

- exaggeration

- “making a fuss”

Some children were left vomiting, dehydrated, or in severe pain before anyone intervened.

This teaches:

- “My needs are inconvenient.”

- “My pain is not believable.”

- “Asking for help is risky.”

These lessons follow people into adulthood.

Threatening to Send the Child Away

Many children grew up genuinely believing they were about to be abandoned. Some adults escalated threats by packing a child’s belongings, putting them in the car, and driving to an unfamiliar location.

Phrases like:

- “We’re taking you to the naughty children’s home.”

- “They’ll look after you now because we can’t.”

…were not “lessons” or “jokes.” They were moments of absolute terror.

Children remember:

- the bags

- the drive

- the building

- the pleading

- the panic in their bodies

Even after returning home, the child remains flooded with fear and confusion.

This teaches:

- “My place in this family is conditional.”

- “Love can be withdrawn at any moment.”

- “If I behave wrong, I will be taken away.”

These threats burrow deep into the nervous system and can shape fear of rejection, people-pleasing, and abandonment for decades.

Using Monsters or “Boogie Man” Threats

Some adults didn’t simply mention the boogie man — they created him.

This often included:

- making noises at night

- hiding under the bed

- scratching at doors

- whispering threats

- creating fear-based rituals

To a child, this isn’t imagination.

It is real.

The child’s nervous system responds as though danger is present.

This teaches:

- “The world is unsafe.”

- “Fear is unpredictable.”

- “Adults will amplify my terror instead of soothing it.”

Instead of learning comfort and protection, the child learns hypervigilance and dread.

The Impact on a Child’s Nervous System

When the adults responsible for safety behave unpredictably or dismissively, the child’s body adapts for survival:

Fight

Anger, frustration, challenging behaviour.

Flight

Withdrawing, hiding, avoiding conflict.

Freeze

Shutting down, dissociating, going numb.

Fawn

People-pleasing, over-apologising, trying to be “good enough.”

These are not personality traits — they are survival strategies.

Children raised this way often grow into adults who:

- struggle to trust themselves

- doubt their intuition

- fear conflict

- override their own needs

- apologise for existing

- avoid asking for help

- don’t know what safety feels like

The body remembers what the environment taught.

How This Passed Through the Generations

Adults who were raised with “seen and not heard” expectations often took one of three paths:

1. Repeating the pattern

Not out of cruelty,

but because they believed:

- “That’s just how you parent.”

- “It didn’t do me any harm.”

- “This is normal.”

The cycle continued unconsciously.

2. Becoming transactional

Some tried to avoid repeating the emotional harshness, but didn’t know how to offer safety or connection.

So they offered:

- gifts

- food

- treats

- trips

Love became expressed through possessions.

Children became outwardly cheerful while hiding deeper unmet needs.

3. Breaking the cycle completely

These are the cycle-breakers — the ones who felt the impact and made a deliberate decision:

“It ends with me.”

They:

- healed

- sought understanding

- learned emotional regulation

- practised compassion

- created safety

- broke patterns

- raised children differently

- supported others to heal

These are the people changing the world quietly but profoundly.

The Children Who Saw It Clearly

Some Children Knew It Was Wrong — Even Then

Not every child in these environments recognised the behaviour as harmful.

But some did.

Some children — even at four, five, six years old — saw the truth with startling clarity.

These children grew up with a sense of internal knowing that something was deeply wrong, even when every adult insisted:

- “It’s just a joke.”

- “Don’t be so sensitive.”

- “You’re imagining it.”

- “All children get treated this way.”

So why did some of us see it instantly?

Because our nervous systems were already attuned to danger and injustice.

We were operating from a heightened state of awareness — a kind of early neuroception that sensed:

- emotional shifts

- power imbalances

- fear in others

- unfairness

- contradiction

- dishonesty masquerading as humour

- the difference between care and control

Some children develop this sensitivity because:

1. They were natural empaths

Highly attuned children feel the emotional temperature in a room instinctively.

Their bodies register distress — even when words say otherwise.

2. They had to protect others (often siblings)

When a younger sibling was frightened, crying, or confused, some children stepped into the protector role.

Their sense of justice became sharpened by necessity.

3. They were already in survival mode

Children who lived in unpredictable homes developed hyperawareness as a form of safety:

- watching adult expressions

- reading micro-shifts in tone

- anticipating danger

- detecting inconsistency

- preparing for emotional storms

This wasn’t “sensitivity.”

It was survival intelligence.

4. They saw beyond performative kindness

Some adults were gentle in public but harsh in private.

Children who noticed this discrepancy quickly learned:

- “Something is off.”

- “People aren’t always who they pretend to be.”

- “What adults say doesn’t match how they act.”

That mismatch is deeply informative to a perceptive child.

5. They had intact moral clarity

Some children simply knew — without being taught — that cruelty was wrong.

Their internal compass was strong, and no amount of denial could dull it.

This heightened awareness shaped who we became

The children who saw the truth often grew into:

- protectors

- cycle-breakers

- advocates

- helpers

- counsellors

- truth-tellers

- deeply compassionate adults

- people who feel injustice viscerally

- people who sense dysregulation in others instantly

Because the nervous system remembers.

Seeing cruelty early doesn’t damage the moral compass — it refines it.

These children grew up with a kind of clarity that many people reach only after decades of healing.

They didn’t just survive the environment.

They understood it.

Even when no one else could.

Even when adults denied it.

Even when speaking the truth got them punished, dismissed, or called “too sensitive.”

But that clarity — that early awareness — is exactly why so many of them move into protective professions, in teaching, emotional support and safeguarding. It is exactly why I teach Social & Emotional Learning (SEL) — it’s not an add-on, it’s an essential life skill for a healthier nervous system, a healthier life, and ultimately a healthier world.

A Common Question People Ask

“If adults passed on these behaviours because they didn’t know any better… then how did I, as a child, know something was wrong when I wasn’t taught anything different?”

This is a powerful and important question.

Some children develop heightened moral clarity and internal truth-recognition precisely because of what they witness.

Their nervous systems become so attuned to fear, contradiction, and injustice that they instinctively sense when something is fundamentally wrong.

They didn’t learn it from adults.

They learned it through:

- observing

- feeling

- surviving

- tuning into emotional reality rather than words

It is not something taught.

It is something felt, deeply and unmistakably.

This intuitive clarity is a sign of a child whose empathy, intelligence, and moral grounding were already strong — despite the environment.

Those Children Are the Real Trauma-Informed Revolution

Real trauma-informed practice didn’t begin in training rooms or policy documents.

It began decades ago in the bodies and hearts of children who recognised harm before anyone explained it.

The ones who saw the truth early — are the real trauma-informed revolution.

Because they:

- lived the impact firsthand

- broke the cycle instinctively

- became protectors and truth-tellers

- developed deep emotional intelligence

- learned to read dysregulation without words

- understand safety because we lived without it

- bring embodied wisdom, not tick-box knowledge

- lead with compassion, not compliance

Trauma-informed isn’t a certificate.

It’s a way of being born from surviving — and transforming — what wasn’t okay.

They didn’t just endure the past.

They turned it into purpose.

Empathy Without Boundaries Is Not Compassion — It’s Self-Abandonment

Empathy is often celebrated, but rarely understood.

What most people don’t realise is this:

Empathy without boundaries is destructive.

Children who grew up scanning rooms, soothing adults, and absorbing distress often grow into deeply empathetic adults — but without the skills or safety to protect themselves.

Unhealed people who learned to manipulate, guilt, or emotionally pull on others will use that empathy against you.

They will drain your:

- energy

- time

- sense of worth

- emotional bandwidth

- self-belief

Not because empathy is wrong — but because they have no boundaries, and therefore you don’t either.

This isn’t harshness.

It isn’t selfishness.

It isn’t “going cold.”

It is self-care, self-worth, and dignity.

Healthy empathy has boundaries.

It feels for others without abandoning self.

It supports connection without sacrificing safety.

Learning this is transformation — the moment empathy stops being a survival strategy and becomes a healthy, grounded, life-enhancing strength.

SEL Isn’t Just a Solution — It’s a Response to Generational Conditions

We talk about teaching Social & Emotional Learning (SEL) to parents, children, workplaces, and services — and it is essential.

SEL builds emotional regulation, empathy, boundaries, and safety in ways that transform lives.

But to truly understand why SEL is needed, we have to step back and ask:

Where did these harmful patterns begin?

What created them in the first place?

We can’t talk about protecting children without also being honest about the conditions that shaped the adults who raised us.

The emotional harm many children experienced didn’t appear in a vacuum.

It was shaped by forces far bigger than the family home:

- War

Generations returned home carrying trauma, dissociation, and shut-down feelings — emotional numbness mistaken for strength. - Poverty

Chronic stress, uncertainty, and survival-mode parenting that leaves no room for emotional softness. - Injustice and inequality

Communities living under pressure develop coping mechanisms, not emotional skills. - Systemic abuse

Institutions that shamed, silenced, punished, and repressed children and parents alike. - Cultural norms

“Children should be seen and not heard.”

“Crying is weakness.”

“Don’t answer back.”

“Respect is obedience.”

These conditions created:

- stressed adults

- dysregulated nervous systems

- emotional shutdown

- generational trauma

- harsh survival strategies

- homes built on fear instead of safety

- the belief that harshness = good parenting

And this is important:

To place the responsibility solely on parents is just more of the same thinking — another loop of the same cycle, another form of victim-blaming disguised as accountability.

Parents can only give what they were given.

Communities can only echo the conditions they were shaped by.

This is why SEL matters so deeply:

SEL didn’t emerge to “fix” people —

it emerged because generations were never given the conditions to emotionally grow.

SEL teaches the life skills many adults never received because their parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents were surviving systems, pressures, wars, expectations, and cultural norms that never allowed emotional safety to flourish.

Understanding this doesn’t excuse harm — but it gives us the compassion and context needed to break the cycle at its roots.

Not Everyone Is Ready to See This Through a Compassionate Lens — and That’s Okay

It’s important to acknowledge that not everyone who lived through these patterns is ready to view them compassionately.

And that is completely okay.

Healing is not linear.

It’s not tidy.

And it isn’t the same for everyone.

Some people are still in the stage where:

- the memories feel raw

- anger is necessary

- the wounds are too deep

- the nervous system is still protecting them

- compassion feels like minimising what happened

- understanding feels like betrayal

- even reading about these dynamics brings up emotion

For many, compassion is the final chapter of healing, not the first.

No one should ever be rushed there.

Every emotional stage — anger, grief, distance, disbelief, clarity — is valid and part of the process.

The goal is not to force forgiveness or understanding.

The goal is to offer space, safety, and recognition so people can heal at their own pace.

When people feel safe enough, compassion often arises naturally — not towards the harm, but towards the human complexity behind it.

Why Adults Behaved This Way (A Compassionate Lens)

Many adults who used harmful behaviours:

- were overwhelmed and unsupported

- repeated what they experienced

- struggled with shame or emotional immaturity

- mistook control for safety

- were never taught empathy

- panicked internally and acted externally

- appeared kind publicly but were exhausted privately

- genuinely didn’t understand the impact

This doesn’t excuse harm.

But it helps explain it — and understanding is how cycles finally end.

Healing Is Real and Happening

Here is the hope:

We are the first generation able to talk openly about this.

We can see the patterns.

We can name them.

We can understand them through the lens of the nervous system.

And most importantly —

we can choose differently.

People are healing.

Parents are learning.

Children are safer.

Communities are becoming more trauma-informed.

Cycles are being broken every day.

Awareness with compassion is powerful.

Truth spoken gently is transformative.

And healing is a journey that many are walking — for themselves, for their families, and for the next generation.

We don’t change the future by blaming the past.

We change it by understanding, growing, and doing better.

And so many people are

What Does a Healthy Childhood Look Like?

After talking about so much of what went wrong for so many of us, it matters deeply to finish by naming what right looks like.

Not perfection.

Not faultless parents.

Just healthy, safe, emotionally attuned care — the kind every child deserves.

A healthy childhood includes:

1. Safety — emotional and physical

A child feels:

- protected

- comforted

- soothed when afraid

- held when hurt

- safe to express any emotion

Safety is the foundation of thriving.

2. Consistency

Children grow strong when adults:

- keep promises

- follow through

- remain predictable

- repair when they get it wrong

Consistency creates trust, and trust creates connection.

3. Boundaries that teach, not punish

Healthy boundaries guide a child, not frighten them.

They sound like:

- “Let’s take a breath.”

- “I won’t let you hurt yourself.”

- “Come sit with me until you feel calmer.”

Boundaries shape security—not fear.

4. Emotional presence

A child needs adults who:

- listen

- validate feelings

- stay calm enough to help

- model emotional regulation

- apologise when needed

Presence teaches children they matter.

5. Freedom to express without shame

Healthy childhoods include:

- laughter

- curiosity

- silliness

- sadness

- big feelings

- questions

- exploration

No child should be mocked or belittled for being human.

6. Encouragement, not comparison

Healthy adults say:

- “I’m proud of you.”

- “Look how hard you tried.”

- “You’re learning.”

- “You’re important.”

The focus is on growth, not perfection.

7. Repair, reconnection, and truth

Every parent gets it wrong sometimes.

Healthy childhoods include:

- apologies

- reconnection

- honesty

- making things right

Repair teaches children that love doesn’t vanish.

8. Space to be a child

A healthy childhood makes room for:

- play

- imagination

- mistakes

- rest

- discovery

- joy

Children should never carry the emotional load of adults.

Healthy childhoods create adults who feel:

- grounded

- secure

- confident

- connected

- worthy

- able to love and be loved

- able to trust and be trusted

This is the vision we move toward when we talk about what went wrong.

Not blame.

Not guilt.

Not shame.

Clarity. Understanding. Healing.

And the commitment to give the next generation what so many of us needed

We are not seeking perfection — life will always bring challenges, obstacles, and moments where we get it wrong.

What we are seeking is kindness, balance, and belonging.

A sense of safety, so the world feels warm and compassionate, not cold and cruel.

And it is important to say this clearly:

It is not weak, soft, naïve, “snowflake,” or pathetic to be kind, gentle, or caring.

Only a dysregulated, defensive nervous system views compassion through that distorted lens.

Regulated adults see kindness for what it truly is:

strength, wisdom, maturity, and emotional leadership.

If we want the world to be a safer place for our children, we must be the ones who model it — in our homes, our communities, and our daily interactions.

Children learn what safety feels like by witnessing it, not by being told about it.

‘The world does not shape our focus. Our focus shapes the world.’ Dr. Joe Dispenza

And when our focus is safety, empathy, truth, and connection, the world transforms — one regulated nervous system at a time.

Your Body Is Wise: And How We Frame Our Responses Shapes Everything

There’s a line that has been echoing in me ever since I read it:

“Your body knows what to do. Your body is wise.” — Yuki Askew - a comment on one of my posts.

It spoke to a truth I have lived, witnessed, and now teach every day.

The Body Speaks Before the Mind Does

There were moments in my life when the dynamics in an environment shifted and, before I had words or conscious awareness, my body knew.

Every cell pulled me to run.

Not a thought.

Not a choice.

A full-body survival instinct.

Some call that a “disorder.”

I call it miraculous early intervention — my body sensing danger long before my mind could register it. That instinct has saved my life more than once. It can feel almost otherworldly, an ancient intelligence rising up to protect me.

And I see this same wisdom constantly in the clients I support.

When I offer grounding techniques, tapping sequences, or simply placing a hand on the heart, I often hear:

“Oh… I already do that naturally.”

“I didn’t realise why that helps me.”

People choose certain music or particular hertz frequencies without knowing the science behind it. They simply say:

“It soothes me.”

Their bodies chose what their minds didn’t yet understand.

Because the body is always trying to regulate, restore balance, and return to safety — often long before we have the language for it.

Where the Real Pain Begins: The Framing

The problem is not the body.

The problem is how people interpret what the body does.

In my own experience, that instinct to run — a profoundly intelligent protective response — was framed as pathology.

And when a survival instinct is labelled as something “wrong,” the person stops trusting themselves.

They shrink.

They hide.

They feel ashamed of the very thing that kept them alive.

It wasn’t the reaction that created the prolonged suffering.

It was the framing of the reaction.

And I see this in so many others:

- A protective instinct becomes “avoidant.”

- A freeze response becomes “lazy.”

- A shutdown becomes “uncooperative.”

- A fear response becomes “dramatic.”

Misunderstanding becomes the second wound — sometimes deeper than the first.

The Impact of Language: What Does “Disorder” Mean When You Already Fear You’re Failing?

This is where language matters more than we realise.

Think about the word “disorder.”

What does that mean to a human being who already fears they’re not coping?

Who already wonders if they’re failing at life?

Who already feels different, overwhelmed, or out of place?

A word like “disorder” can confirm someone’s deepest fear:

“There is something wrong with me.”

But what if the response isn’t disordered at all?

What if it is the exact order the body needed in that moment to survive?

When language frames a survival response as pathology, people internalise shame.

When language frames it as protection, people reclaim self-trust.

The meaning we assign determines the story we live.

Why We Cling to Labels

There’s another truth we rarely talk about:

People often accept labels quickly because they finally provide a reason for what they’ve been fighting alone.

A diagnosis can feel like relief when you’ve spent years being misunderstood — especially when the alternative has been judgment or dismissal.

But imagine if the initial framing had been compassionate and accurate.

Imagine if we already recognised these reactions as the body’s attempt to protect, communicate, and survive.

We wouldn’t need a label to “justify” behaviour.

There would be nothing to justify.

We would already understand.

Ancient Wisdom Modern Science Is Only Just Catching Up With

Long before neuroscience, cultures across the world understood the intelligence of the body:

- Indigenous traditions used rhythm, song, movement, and drumming to create safety and connection.

- African healing systems used call-and-response and communal rhythm to regulate the nervous system.

- Ayurveda emphasised breath, prana, and the inseparable link between body and emotion.

- Traditional Chinese Medicine treated emotions, breath, and organ health as one system.

- Japanese forest bathing (Shinrin-yoku) is now shown to reduce cortisol and activate the parasympathetic nervous system.

Today, polyvagal theory, somatic trauma work, and neuroscience are validating what ancient wisdom always knew:

The body finds a way.

The body remembers.

The body protects.

The body leads.

Imagine If We Framed It Differently

What if our response to someone’s overwhelm wasn’t judgement but curiosity?

What if we said:

“Your body is signalling something important.”

“This reaction has a history.”

“Your nervous system is protecting you.”

“What did your body know before your mind caught up?”

Everything changes:

People stop hiding.

Self-trust begins to return.

Shame loses its grip.

And healing becomes possible — not through force, but through understanding.

When We Change the Framing, We Change the Outcome

My own journey would have looked very different if my earliest instincts had been seen as protection, not pathology.

And that’s why this work matters so deeply to me.

When we honour the wisdom of the body and choose language that reflects truth rather than judgement, we create conditions where healing becomes not only possible — but inevitable.

The body is not the problem.

The body is the guide.

And when we change the framing, we truly do change the outcome.

Positive outcomes begin with - A Positive Start

The Limits of Your Life Are the Limits You Choose” — But It’s Not the Whole Story

I saw a post today that read:

“The limits of your life are the limits you choose.”

At first glance it feels inspiring, almost liberating — as if choice alone shapes destiny.

But it also got me reflecting on something important:

Nothing is relevant until it becomes relevant.

Nothing truly lands until you can apply it to yourself.

Before I say anything more about quotes and self-help books, I want to share something personal.

A friend of mine died in 2023.

We initially met when she approached me for therapy for unresolved trauma.

She was kind, thoughtful, curious, and exhausted — the kind of exhaustion that comes from a lifetime of searching for answers without ever truly finding them.

She told how she had been on every mental health course, workshop, and seminar she could access.

She had tried every kind of medication.

She had read every self-help book ever recommended to her.

She kept trying, kept learning, kept hoping.

The day we met, she had just been diagnosed with stage 4 cancer.

Her wish was to finally make sense of her life, and she was determined to understand - and so, for the next twelve months together we stepped into the world of trauma — gently, compassionately, honestly.

And in that final year of her life, she learned more than she had learned in the previous fifty-nine years combined.

She learned the truth about trauma.

Not the surface-level understanding that so many books offer,

but the deep, embodied reality of how trauma shapes the nervous system, the identity, the sense of self, and the capacity to feel alive.

She learned what it meant to finally be seen.

To make sense of her inner world.

To recognise that nothing was “wrong” with her — her body was responding exactly as it had needed to survive.

When she died, she left me her entire library of over 300 self-help books.

And I often reflect on what those books meant to her.

Not because they failed, but because they were written for a mind she didn’t yet have access to — a mind that only emerges when the nervous system feels safe enough to take in new information.

That experience changed how I think about self-help.

It deepened my understanding that we don’t lack information — we lack regulation.

We don’t lack resources — we lack internal safety to apply what we learn.

She taught me that the search for healing often lives in the pages of books, but the actual healing begins inside the body.

The Search for Answers Outside Ourselves

So many people spend a fortune on the latest self-help book or training program.

We read the first chapter.

We complete the first two modules.

Then we buy another one, hoping this will finally be the answer.

Dr Wayne Dyer used to say this is like losing your keys in the house but going outside to look for them.

You’ll never find them — but you keep searching outside anyway, convinced the solution must be “out there.”

And isn’t that how so many of us live?

Especially when we’ve grown up in environments where our internal world wasn’t nurtured, recognised, or supported.

We keep looking for external fixes because internally, we don’t yet know where — or even who — we are.

A Quote That Changed My Trajectory

I remember many years ago sitting in a solicitor’s waiting room.

On the wall was a simple framed quote by Henry Ford:

“If you think you can, or you think you can’t, you’re probably right.”

I must have read it a dozen times before my appointment.

I’d never heard it before.

And it blew my mind.

Not because it was intellectually profound, but because no such idea had ever entered my world.

I turned the meaning over and over in my mind.

It was a complete contrast to the hopelessness I lived with — a life where nothing felt possible and the evidence of that impossibility showed up everywhere. Just has it had for my friend, Alison.

Suddenly this sentence suggested the opposite.

“If that’s what you think, you’re probably right.”

It confused me a little…

but on some deeper level, it connected.

Something in me recognised that thought alone might not change my life — but it could open a door.

When Dorsal Vagal Shutdown Defines Your Reality

It’s difficult to explain the dorsal vagal space to someone who has never experienced it.

How can you describe a world where everything feels limited?

Hopeless?

Where control is non-existent?

It’s like living in another dimension.

You can see with your physical eyes that joy, love and peace exist.

You can watch other people laughing, connecting, building lives.

But there is no comprehension of it… and absolutely no felt sense of it.

It belongs to them, not you.

It’s for other people in other lives.

When you’re in dorsal, your mind doesn’t say, “I’m limited because of my nervous system.”

It says, “I can’t. I never could. And I probably never will.”

Which is why motivational quotes — even the good ones — often feel like they’re written for someone else.

When Dorsal Vagal Shutdown Becomes Your World

Trying to describe the dorsal space to someone who hasn’t endured it is like trying to explain darkness to someone who has only ever known light - where do you begin?

People often describe nervous system states as emotional “modes,” but this one is far more than that.

Dorsal isn’t just a state — it’s a destination.

A world.

A landscape with its own rules, colours, textures, and gravity.

It is:

- dark

- dirty

- dank

- heavy

- hopeless

- frightening

- lonely

- disconnected

- isolating and distant

It is an internal world that becomes an external world.

Your entire existence — inside and outside — gets filtered through the same lens.

When you are in dorsal, you don’t simply feel limited.

Your environment becomes an expression of your internal collapse.

Your home might become disorganised, untidy, or even squalid.

Not because you don’t care — but because your life force is switched off.

Your space often mirrors your nervous system.

Your world becomes a visual map of your inner disconnection.

But the opposite can also be true — and it’s just as misunderstood.

Not everyone living in dorsal looks like they’re collapsing.

Some people have:

- money

- cars

- luxury

- a beautiful home

- impeccable grooming

- a curated lifestyle

- a polished persona

From the outside, it looks like success.

On the inside, it is chaos.

This is the height of persona — the desperate attempt to construct a perfect external world because the internal world feels unmanageable, unsafe, or in pieces.

For these individuals, the shutdown, numbness, and disconnection doesn’t show up in their environment.

It shows up in:

- their relationships

- their isolation

- their inability to feel joy

- their chronic over-functioning

- their exhaustion

- their sense of emptiness

- their collapse behind closed doors

Both experiences are expressions of the same internal landscape — the world of dorsal.

One is visible.

One is invisible.

Both are equally real.

Why this distinction matters

Professionals who have never lived in that landscape often misinterpret what they see.

If the outer world is chaotic, they judge the “mess.”

If the outer world is polished, they miss the suffering entirely.

But both are coping strategies.

Both are nervous system adaptations.

Both are attempts to survive a world that feels overwhelming or unreachable.

To understand the dorsal space is to see beyond the physical environment — whether that environment looks like collapse or looks like perfection — and into the inner world that shapes it.

It’s not laziness, dysfunction, or self-neglect.

And it’s not shallowness, vanity, or overachievement.

It’s survival.

A survival strategy expressed either through external disorder or external perfection.

And both deserve compassion, not judgment.

When Professionals Judge the Symptoms, Not the Landscape

This is where something vital gets missed — especially by professionals who have never lived in that terrain.

When someone shows up in a dorsal state, their environment often shows it too.

Not because they’re choosing it, but because their survival response has taken over.

Yet too often the external signs — the mess, the disorganisation, the shut-down — become the target of judgment.

Words like:

- “unmotivated”

- “chaotic”

- “neglectful”

- “unfit”

- “dysfunctional”

When your internal world is collapsing and professionals judge the outer expression of that collapse, it feels deeply unjust.

It feels like victim-blaming, because it is.

To understand the dorsal space is to see beyond the physical environment into the inner landscape — the one most people never see.

Dorsal creates a whole world, not just a feeling.

And when professionals misunderstand that, people already buried in collapse become buried further under shame.

Why “Choice” Isn’t the Whole Story

This is why the phrase “the limits of your life are the limits you choose” can feel both true and untrue at the same time.

It’s true in the sense that our beliefs shape our behaviour.

But it’s incomplete — and even unfair — without understanding how trauma alters the nervous system.

Your ability to “choose differently” is shaped by:

- your environment

- your internal state

- your past experiences

- your neuroception

- and your core beliefs formed in survival

Choice cannot override a dysregulated nervous system.

Thought cannot override immobilisation.

A positive affirmation cannot cancel out years of survival-based wiring.

Mindset is not the starting point — it’s the result.

This is why so many people read self-help books and feel nothing changes.

It’s not because they’re lazy or unmotivated.

It’s because they’re trying to use top-down tools to solve bottom-up conditions.

Bottom-Up Before Top-Down

We cannot think ourselves into healing.

We feel our way there.

From the bottom up.

The answers are not in the next book, the next program, or the next external teacher.

They’re inside us.

But they are buried under layers of survival strategies, protective patterns, and nervous system responses that developed for very good reasons.

When the body feels safe,

the mind becomes available.

When the nervous system is regulated,

possibility suddenly appears where hopelessness once lived.

When we are connected internally,

external wisdom finally makes sense.

This is why things only become relevant when we’re ready to receive them.

Not because the ideas weren’t valuable before…

but because we didn’t yet have access to them.

The Real Meaning Behind the Limits We “Choose”

So when I hear the phrase again — “the limits of your life are the limits you choose” — I interpret it through a trauma-informed lens.

Yes, our beliefs shape our direction.

Yes, internal narratives matter.

Yes, mindset plays a role.

But that mindset is shaped by:

- our history

- our nervous system

- our experiences

- and our capacity in the present moment

For someone in a regulated, supported state, choice feels empowering.

For someone in dorsal, it feels impossible — or worse, shaming.

And that distinction matters.

Because healing isn’t about forcing new thoughts.

It’s about creating the physiological conditions where new thoughts become available.

The Keys Were Never Outside

Dr Wayne Dyer’s metaphor stays with me.

We keep looking for our keys outside, even though we lost them inside.

Everything we’re searching for — safety, clarity, confidence, connection — is internal work.

Not the easy kind.

Not the overnight kind.

But the honest, compassionate, body-based kind.

And when the body shifts, the mind shifts.

That’s when the quotes land.

That’s when ideas resonate.

That’s when relevance appears.

That’s when possibility feels real.

Because the truth is this:

The limits of your life are not the limits you choose.

They’re the limits you’ve learned.

And learned limits can be rewired.

Not through self-help alone.

Not through positive thinking alone.

But through nervous system regulation, relational safety, truth, connection, and compassionate self-understanding.

In the end, the limits you “choose” are simply the limits you finally become free enough to see beyond.

And that freedom begins from the inside out

Alison’s Legacy Lives On

Today, in honour of her journey and her generosity, Alison’s reference library is available for our clients, students, and practitioners to borrow from. It stands as a reminder that while the answers ultimately live within us, sometimes a single sentence, a single book, or a single moment of connection can become the light that guides us home. Her library continues to support others on their path, and her legacy lives on in every person who finds comfort, insight, or curiosity within its pages.

How Trauma Held in the Body Shapes Our Thoughts, Behaviours, and Vulnerabilities

Trauma isn’t just something that happened to us — it’s something that lives in us.

It lives in our bodies, in the patterns we learned to survive, and in the emotions we pushed down because they were too much to hold at the time.

When old wounds stay unhealed, they don’t disappear.

They simply go underground — shaping our thoughts, behaviours, and relationships in ways we often don’t recognise.

Trauma in the Body → Reactions in the Present

When the body senses something as threatening or unsafe, it doesn’t check whether the danger is happening now or in the past.

It simply reacts.

This is why so many people:

- mask

- fawn (people-please)

- shrink themselves

- try to appear “normal”

- work hard to belong

- pretend they don’t care

Underneath these behaviours are hurts that need attention, not shame.

Emotions are messages. They say:

“Something inside needs care and awareness.”

How Trauma Disconnects Us From Ourselves

Trauma doesn’t just leave memories — it reshapes the way we experience ourselves.

When we grow up or live through situations where our needs were ignored, dismissed, or punished, the body learns:

“My feelings are too much. My needs don’t matter. My truth is unsafe.”

To survive, we disconnect:

- from our bodies

- from our instincts

- from our emotions

- from our boundaries

- from our sense of worth

- from the internal signals that guide us

This disconnection isn’t dysfunction — it’s protection.

The Body Remembers What the Mind Tries to Forget

We can appear calm, capable, and “fine” to others while internally living in constant vigilance.

Survival mode has one priority:

Get through it. Don’t feel it. Stay safe.

Over time, we become strangers to our own inner world.

What Disconnection Looks Like

Instead of understanding our emotions, we override them.

Instead of recognising our needs, we minimise them.

Instead of trusting our instincts, we silence them.

Instead of listening to discomfort, we push through it.

Instead of setting boundaries, we collapse them.

Instead of being who we are, we perform who we think others want us to be.

This is why trauma responses are often invisible on the outside and painfully loud on the inside.

Signals We Stop Hearing

Trauma disconnects us from the signals meant to keep us safe:

- the tightening in the chest when something feels off

- the gut instinct that says “this isn’t right”

- the discomfort when a boundary is crossed

- the exhaustion signalling overwhelm

- the sadness showing where we hurt

- the anxiety showing where we’re afraid

We numb, dismiss, or override these signals.

But numbed signals don’t disappear — they simply guide us from the shadows, shaping our reactions without our awareness.

The Cost of Disconnection

When we are disconnected from ourselves:

- we don’t see our own vulnerabilities

- we miss our own red flags

- we override our needs

- we question our intuition

- we repeat the same painful dynamics

- we read everyone else’s emotions but ignore our own

- we mistake survival patterns for personality

- we become easier to manipulate, pressure, or overwhelm

This is why understanding your own “white flags” is vital — not as blame, but as protection.

The Mirror Effect

When we’re disconnected from our own wounds, we often misjudge others.

We dislike in other people the traits we’d rather not admit in ourselves.

Not because we are judgemental, but because our nervous system tries to protect us from anything that might expose our pain.

The truth is:

There is no one more vulnerable than the person who believes they have no vulnerabilities at all.

The STAND Three-Flag System

In our STAND program, we use three types of signals to help people recognise safety, risk, and vulnerability — both externally and internally.

🟢

Green Flags

Signs that someone is safe, grounded, and trustworthy.

🔴

Red Flags

Behaviours signalling caution — early signs of manipulation, control, or harm.

⚪

White Flags

Your own vulnerabilities — the emotional areas where you are most easily influenced, pressured, or harmed.

White flags are not weaknesses.

They are parts of you asking for compassion, understanding, and protection.

A Real Example: When White Flags Are Exploited

A friend of mine unknowingly entered a relationship with a narcissist.

He cheated, emotionally abused her, and slowly eroded her sense of self.

When she finally left, he said:

“You were easy to target because you were desperate to be loved.”

It sounded cruel, but beneath it was a terrible truth.

She was desperate to be loved.

Not because she was weak, but because years of loneliness and trauma had made her crave connection so deeply that she tolerated the intolerable.

And he saw it — immediately.

Like many narcissists, he mirrored her unmet needs perfectly, pretending to be her ideal partner.

He wasn’t reflecting who he was.

He was reflecting her white flags.

This is how white flags work:

- They show us where we are emotionally exposed.

- They help us understand what makes us vulnerable.

- They help us prevent harm and break patterns.

This is not victim blaming.

This is self-awareness and self-protection.

Reconnection Is Healing

Healing is not about perfection.

It’s about coming home to yourself.

It’s:

- hearing the body’s whispers again

- naming emotions instead of numbing them

- recognising early warning signs

- honouring your needs without apology

- trusting your intuition

- choosing relationships that feel safe

Reconnection brings clarity.

Clarity brings choice.

And choice brings freedom.

And Healing Matters Deeply for Our Children

Our trauma never stays contained.

It spills.

It spills into: