Social Emotional Literacy: The Essential Life Skill That Shapes Our Future

Social Emotional Literacy (SEL) is not “soft.”

It’s not optional.

It’s not a luxury for some.

SEL is the foundation of human connection, healthy relationships, emotional stability, community wellbeing and societal transformation.

It is the essential life skill — shaping how we understand ourselves, how we relate to others, and how we participate in the world.

Why SEL Matters Across Every Part of Society

Early Learning

Children grow when they feel emotionally safe.

SEL helps them develop trust, curiosity, empathy and the secure foundation that supports lifelong resilience.

Education

Schools with SEL woven into their culture experience fewer behavioural crises, calmer classrooms, compassionate communication, and stronger academic outcomes.

A regulated nervous system learns more easily.

Workplaces

SEL reduces burnout, conflict, absenteeism and stress-related illness.

It strengthens collaboration, boundaries, and psychological safety — the real drivers of innovation and productivity.

Communities

SEL builds connection, compassion, understanding and social trust.

It turns fragmented environments into places of belonging and care.

SEL Saves Lives — and Resources

When people can understand and regulate their emotions, we see fewer mental health crises, fewer exclusions, fewer high-cost interventions, and healthier families and communities.

Prevention is always more cost-effective — and infinitely more humane — than reaction.

The Importance of Secure Attachment, Authenticity and Belonging

At the heart of SEL lies something profoundly human:

our need for secure attachment, authenticity, and belonging.

These aren’t emotional extras.

They are biological necessities.

Secure Attachment

Built through attunement, presence, repair, and emotional safety.

It forms the basis of:

- trust

- self-worth

- resilience

- emotional regulation

- and healthy relationships

Where this safety wasn’t available early in life, adults often struggle to regulate emotions, hold boundaries, or feel safe with others.

Authenticity

Trauma teaches people to hide.

SEL teaches people to return to their truth.

Authenticity is the foundation of mental health, healthy boundaries, and self-respect.

Belonging

We are hardwired to belong.

Belonging isn’t created by pressure or performance — it grows where people feel seen, valued and safe.

When secure attachment, authenticity, and belonging are present, individuals and communities thrive.

Why Unmet Early Needs Echo Through Adult Lives

Dan Siegel’s Interpersonal Neurobiology (IPNB) explains that we are born wired to receive a certain quality of care:

- emotional presence

- soothing

- co-regulation

- attunement

- safety

- connection

When this isn’t consistently available — for any reason — the need does not disappear.

The body continues to long for what it didn’t receive.

Many adults describe this as:

- a deep emptiness

- an inner void

- a hollow ache

- an unnameable longing

- difficulty soothing themselves

In the absence of learned self-regulation, many try to fill the void through food, substances, relationships, achievements or possessions — not out of weakness, but because the nervous system is seeking the care it was wired for.

Co-Regulation Before Self-Regulation

Infants don’t self-regulate.

They borrow the regulation of the adults around them.

Without enough co-regulation in childhood, self-regulation in adulthood becomes incredibly difficult.

SEL gives adults the emotional education they never received — the skills needed to finally meet their own needs safely, compassionately and effectively.

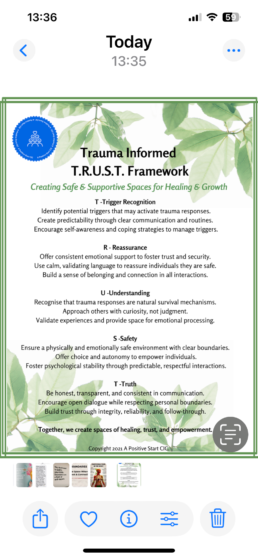

Our Trauma-Informed TRUST Framework

Trigger Recognition• Reassurance • Understanding • Safety • Truth

TRUST creates relational safety for those who never experienced emotional safety growing up.

It recreates the conditions required for secure attachment:

- attunement

- pacing

- presence

- compassion

- co-regulation

- and truth

For many, TRUST becomes their first experience of safe, grounded, dependable connection.

The 7Rs Pathway to Purpose

The 7Rs Pathway to Purpose is more than a framework — it is the journey of recovery itself.

It reflects the natural, human process of healing from trauma, rebuilding trust in ourselves, and reclaiming purpose and identity.

Each step mirrors what happens in a regulated, trauma-informed healing journey:

- Recognise – noticing your internal world with honesty

- Reconnect – returning to your body, breath, and truth

- Regulate – creating safety in your nervous system

- Reframe – transforming old narratives into understanding

- Reimagine – expanding what feels possible

- Rebuild – taking grounded steps toward change

- Rise – stepping into your full potential, authenticity, and purpose

This is the arc of recovery — the movement from survival to healing, and from healing to growth.

It aligns with the way the brain and nervous system naturally repair, rewire, and reorganise when supported by safety, compassion, and connection.

SEL Is Strength, Not Weakness

Labels like “snowflake,” “too soft,” or “children should be seen and not heard” belong to a disconnected era.

SEL is not weakness.

It is:

- courage

- emotional intelligence

- integrity

- relational wisdom

- safety

- healing

- and leadership

Trauma is about disconnection.

SEL is about connection — to self, to others, to purpose, and to the communities we build together.

SEL is awakening — the return to our deepest human truths.

SEL is evolution — the natural progression toward compassion, emotional safety, and collective wellbeing.

This is what Dan Siegel calls MWe —

me + we - the integrated world we co-create when we feel safe, connected and whole.

A Positive Start CIC: Community at the Heart

A Positive Start CIC is a Community Interest Company — we exist solely for the benefit of our community.

Our logo — five smiling figures gathered beneath a blue heart — represents what we stand for:

- community togetherness

- co-regulation

- compassion

- emotional safety

- and the shared humanity at the core of SEL

Everything we create — from the TRUST Framework to the River Room Songbook — is designed to strengthen connection, belonging and emotional wellbeing.

This Is Not Political — It’s Human

Social Emotional Literacy is not a political issue.

It is not “left” or “right.”

It is not ideology or culture wars or who is “too soft.”

SEL actually lives in the middle —

in balance, in integration, in the calm centre where groundedness meets compassion.

It is:

- emotional balance

- nervous system balance

- relational balance

- the balance between thinking and feeling

- the balance between self and other

- the balance between boundaries and empathy

SEL is not about division.

It is about integration.

It is not political — it is biological.

It is not about sides — it is about centre.

It is not about ideology — it is about human wellbeing.

SEL strengthens families.

SEL strengthens workplaces.

SEL strengthens communities.

SEL strengthens society.

SEL is the middle ground where humanity reconnects.

SEL is about health, safety, connection, and wellbeing.

It is about:

- how our nervous systems function

- how trauma shapes behaviour

- how humans learn to regulate

- how we create emotionally safe environments

- how children form secure attachment

- how adults heal from what they didn’t receive

- and how communities reduce harm, conflict, and crisis

It is relational.

It is human.

It is the thread that binds us together, beyond opinion, beyond division, beyond labels.

Free Trauma-Informed Resources

All available via the QR codes in the accompanying graphic:

- River Room Songbook for Children

- TRUST Framework (free PDF)

- TRUST Facilitator Worksheets

- STAND – Parents As Protectors Programme

Each resource supports emotional literacy, safety, connection and healing.

A Vision for the Future

Imagine a world where:

- every child learns SEL from birth

- every school cultivates emotional safety

- every workplace values compassion

- every community feels connected

- every adult knows how to regulate, repair and relate

- and healing is not the exception but the expectation

This is possible.

It begins with Social Emotional Literacy —

and with the courage to build a world where compassion, connection and belonging are the norm.

Free Resources

- River Room Songbook for Children

https://apositivestart.org.uk/the-river-room-songbook/ - TRUST Framework (Free PDF)

https://apositivestart.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Free-Resource-Trauma-Informed-TRUST-Frameworkpdf.pdf - TRUST Facilitator Worksheets (PDF)

https://apositivestart.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/TRUST-Facilitator-worksheets-pdf.pdf - STAND – Parents As Protectors

https://apositivestart.org.uk/stand-parents-as-protectors/

The Journey Before The Journey

If you’d asked me where A Positive Start began when I first started this work, I would’ve confidently said:

“It began because of the domestic violence.”

At the time, that felt true.

It felt obvious.

The dramatic moment. The crisis. The breaking point.

The event that almost ended my life.

But what I discovered as the journey unfolded — as I tracked my recovery with genuine curiosity, compassion, and a willingness to see beyond the obvious — was that the real beginning wasn’t the trauma I believed had “created” the problem.

That moment was only a symptom.

An eruption at the end of a long, invisible fault line.

The real story had begun decades earlier, buried in belief systems I didn’t know I held, shaped by nervous system responses I didn’t yet understand, and woven through patterns I thought were “just who I was.”

What I thought was the beginning was actually the middle.

And that realisation changed everything — including the birth of A Positive Start CIC.

Learning to Track the Journey Instead of the Events

When I first began to look back, I did what many trauma survivors do:

I focused on the “big” events.

The obvious pain.

The memories we circle around because they feel like the milestones that broke us.

But recovery has a way of peeling back layers we didn’t expect.

I began to notice themes.

Patterns.

Internal reactions that didn’t match my external reality.

Moments when I “collapsed” inside while appearing fully functional on the outside.

For the first time, I started to track my nervous system, not just my emotions or thoughts.

And what I uncovered was something I had lived with for so long that I didn’t even know it had a name.

Dorsal vagal collapse.

A dark, heavy, numb place.

Not dramatic.

Not chaotic.

Just a quiet, hollow emptiness.

A sense of peering into the abyss from the inside.

And here’s the truth I wrestled with:

I had lived in that state for most of my life without realising it.

I didn’t know what ventral vagal safety truly felt like.

I had moments of peace — but they were fleeting, usually happening when I was engrossed in an activity that pulled me above water just long enough to breathe before I sank back down again.

Ventral was not a home.

It was a holiday I didn’t know how to book twice.

From dorsal, ventral didn’t just feel far away — it felt unimaginable.

Something I watched other people experience like an observer through glass.

Something I deeply wanted but couldn’t comprehend for myself.

And that sentence — “I can’t imagine that for me” — became the turning point.

Because it wasn’t just me.

Recognising the Same Patterns in Others

When I worked with people the DWP labelled “the farthest from the labour market,” I recognised the same gaze I carried for so many years:

that sense of ventral being “for other people.”

They weren’t failing.

They weren’t unwilling.

They weren’t stuck because they lacked ambition.

What they lacked was a self-belief system that recognised possibility.

Their nervous systems had been shaped by experiences long before adulthood — experiences that conditioned them to expect shame, failure, disappointment, and rejection.

And here’s the thing trauma teaches you:

If you believe something deeply enough, the nervous system will make it feel like truth.

Even if it isn’t.

This is why you can desperately want a better life — but your actions still pull you back into familiar patterns.

Not because you’re broken.

Not because you’re incapable.

But because your mind is trying to protect you by keeping you in what feels predictable.

I saw myself in them.

They saw themselves in me.

And that’s when I realised:

The journey didn’t start at the trauma.

It started with the beliefs we learned about ourselves long before the trauma ever happened.

Belief Systems Are Formed Before We Have Words

For most of us, our story doesn’t start with the first major trauma.

It starts with the first moment our nervous system learned that the world wasn’t safe.

My earliest memory of trauma is from around two and a half years old.

I accidentally overdosed — helping myself to what I believed were sweeties, not knowing the danger.

My stomach was pumped.

I lived, physically.

But something else shifted that day.

I share this not for drama, but for clarity:

this is where neuroception began for me —my body’s subconscious scanning for danger, long before logic or reasoning had developed.

What stayed with me wasn’t the medical event.

It was the energy in the room.

The panic.

The anger.

The fear disguised as blame.

The sudden shift from innocence to “you could die,”

“you are silly,”

“you are stupid,”

“you can’t be trusted.”

Children don’t hear words — they absorb meaning.

And the meaning I absorbed was this:

I am the problem.

I cause distress.

I disappoint people.

My parents weren’t cruel. They were terrified.

They were ‘authoritarian’ - from the ‘children should be seen and not heard’ era, and dysregulated by their own experiences. I was their first born, I didn’t come with instructions - and they were terrified.

But their dysregulation became the foundation of my self-belief.

And once that foundation is laid, life builds upon it — until it becomes a house you don’t realise you’re living in.

The body keeps the score long before the mind keeps the memories.

As I continued tracing the threads further back, I began to realise that my body had been trying to warn me for years — long before I understood the language it was speaking.

At age nine, I had a tumour removed from my appendix.

At the time, this was treated purely as a medical event, but when I look back now through a trauma-informed lens, I can see it as another sign of a nervous system living in constant survival mode. My body had been running on adrenaline for so long that it was no longer functioning from a place of safety; it was reacting, protecting, bracing — even at an age when I should have been carefree.

Through my teens and into adulthood, the physical symptoms increased.

I experienced vasovagal syncope, fainting episodes that struck suddenly as though my vagus nerve simply overloaded and shut down. At the time, no one connected it to stress or dysregulation. But now I understand exactly what was happening:

My vagus nerve was signalling overwhelm.

My body was saying, “This is too much.”

Alongside this came migraines, IBS, digestive issues, and a deep sense that my body was fighting quiet battles I couldn’t interpret. These weren’t random medical problems — they were somatic messages, the body expressing what my conscious mind had never been allowed to feel or articulate.

And now, after the work I’ve done to reconnect and regulate, something remarkable has happened:

Those symptoms are gone.

No fainting.

No IBS.

No migraines.

Not because life suddenly became easy, but because I finally learned to listen to my body with understanding instead of fear. Once I found language for my experiences — dorsal collapse, hypervigilance, nervous system overload — the physical expressions of that stress no longer needed to shout for my attention.

My body had been keeping the story long before I did.

I just didn’t yet know how to read it.

As these symptoms appeared throughout my childhood and teenage years — the fainting, migraines, IBS, shutdowns, and overwhelm — they were real. They felt real. Anxiety and panic live in both the mind and the body, and when you don’t understand why they’re happening, you reach for the only support available:

You go to the system designed to help you.

But here is where so many of us become lost.

We seek professional advice, hoping for clarity or connection, but instead we are often given labels, diagnoses, and medication without anyone asking the most important question:

“What happened underneath this?”

No one explained the nervous system.

No one recognised trauma.

No one connected fainting episodes, stress physiology, or chronic shutdown with emotional overwhelm.

No one explored belief systems or developmental neuroception.

So the journey ends there — not because we heal, but because the system stops looking.

We become suspended in our own suffering, frozen in place, medicated rather than understood. And when your underlying belief is already “I am the problem,” it is painfully easy to accept the labels placed upon you.

And then the next chapter unfolds almost predictably:

You become too unwell to work.

You go on sickness benefits or unemployment.

You struggle with daily functioning.

You collapse further because the system does not soothe — it often shames.

Society reflects the same beliefs we already carry:

“Scrounger.”

“Lazy.”

“A drain.”

These words echo the beliefs that took root in childhood — the ones already living inside the body.

And dorsal collapse becomes the trapdoor.

It pulls you deeper:

into hopelessness,

into guilt,

into shutdown,

into the place where you feel you don’t belong anywhere — not in work, not in community, not even in your own skin.

The very systems meant to support us often reinforce the deepest shame we already hold.

Not because people are unworthy of support —

but because their suffering is misunderstood at the level of the nervous system, not the behaviour.

And without that understanding, people aren’t supported back into life —

they’re pushed further out of it.

Survival Mode Becomes a Personality When It Lasts Too Long

From an early age, my nervous system was shaped around:

- hypervigilance

- shame

- internal collapse

- overthinking

- self-blame

- low self-worth

- fawning

- acceptance of less

Not because I chose it — but because my survival system chose it for me.

By the time domestic violence entered my life, it didn’t create my lack of self-worth.

It reinforced what I already believed about myself.

That’s the painful truth many survivors eventually realise:

the trauma didn’t invent the beliefs — it confirmed them.

Even when we say we want better, we often behave in ways that contradict that desire — not out of weakness or lack of willpower, but because incongruence is a nervous system response, not a moral failing.

You cannot build a life that contradicts what your nervous system believes about your worth.

And this is why understanding the patterns matters.

Because once you see the patterns, you can finally change them.

And once you change them, the life you build begins to change too.

The Turning Point: Tracking My Own Recovery

The real breakthrough wasn’t an event — it was a shift in how I saw myself.

I stopped asking:

“Why did that happen?”

and began asking:

“What was I believing about myself at the time it happened?”

This single shift changed everything.

Because when you start tracking your internal state rather than the external events, you begin to see how your life has been shaped not by what happened to you, but by what you believed those events meant.

I realised I had spent decades:

- abandoning myself

- normalising collapse

- confusing familiarity with comfort

- confusing chaos with normality

- confusing survival with living

And once I understood that, the journey toward ventral — toward safety, connection, groundedness — finally became possible.

How This Led to the Birth of A Positive Start CIC

A Positive Start CIC wasn’t created at the moment of crisis.

It was created as I slowly pieced together my recovery and understood the real roots of trauma:

the beliefs beneath the surface,

the nervous system states that shape identity,

and the quiet patterns that dictate the lives of people labelled as “hard to reach.”

APS didn’t begin because of domestic violence.

It began because I finally understood the trajectory from:

- early childhood dysregulation

- to survival mode

- to low self-worth

- to unhealthy relationships

- to collapse

- to hopelessness

- to the feeling of being “too far gone”

And I knew — not intellectually, but viscerally —that others were living the exact same journey.

As I healed, I didn’t just want to help people “cope.”I wanted to help them understand.

Because healing doesn’t begin with motivation. It begins with meaning.

And people cannot change their lives until they understand the story beneath the story.

That became the heartbeat of APS.

Not surface change.

Not behaviour management.

Not “fixing people.”

But helping people reconnect with the part of themselves that trauma disconnected them from.

Connection.

Safety.

Regulation.

Awareness.

Understanding.

Self-compassion.

Belief.

Ventral.

This is at the heart of our collaborations — working with people who understand the importance of emotional literacy and emotional safety.

The Deeper Message: We Have to Go Back to Go Forward

People often misunderstand this.

Going back is not about reliving trauma.

It’s not about revisiting painful memories to punish ourselves with them.

It’s about understanding

how the journey unfolded

and why the nervous system shaped itself the way it did.

When you understand where your beliefs came from, you’re no longer controlled by them.

When you understand why you disconnect, you can learn to reconnect.

When you understand why safety feels dangerous, you can slowly rewire what “safe” means.

When you understand why you collapse, you can begin to rise.

Healing isn’t about changing your past.

It’s about changing the meaning your nervous system attached to it.

Because anything is only ever true because you believe it.

And what you believe about yourself is the foundation of everything you build.

Why This Matters for Community Mental Health

The people I support today aren’t broken, resistant, or “hard to reach.”

They’re carrying belief systems shaped in childhood, reinforced by trauma, and never challenged with compassion.

Many of them have lived their whole lives in dorsal collapse.

Many don’t recognise ventral as an option.

Many don’t believe hope is for them.

But I am living proof that:

- survival mode is not a personality

- collapse is not a destiny

- belief systems can be rewritten

- nervous systems can be retrained

- safety can be learned

- connection can be restored

- a life worth living can be rebuilt

This is the heart of A Positive Start CIC.

Not perfection.

Not quick fixes.

But a journey from dark to light — one belief at a time.

The Journey Continues

If I could go back and speak to the version of me who thought domestic violence was the beginning of the story, I would tell her:

“You began your healing long before you realised you needed it.

And the part of you that survived the earliest trauma is the same part that will lead you home.”

A Positive Start CIC was not born from pain.

It was born from understanding.

From tracking.

From curiosity.

From learning to see myself clearly for the first time.

And from the realisation that community mental health must honour the whole journey — not just the parts people can see.

The journey didn’t begin at crisis.

It began with belief.

And belief — rewired through compassion, connection, and safety — is where every new journey begins.

The TRUST Framework: Creating Truly Safe, Trauma-Informed Spaces

This framework is free to use in community, education, care and support settings.

Please credit Deborah J Crozier & A Positive Start CIC when sharing or delivering.

© 2021–2025 Deborah J Crozier, A Positive Start CIC. All Rights Reserved.

Many spaces say they are trauma-informed because they use gentle language, display wellbeing posters, or follow safeguarding procedures. But a trauma-informed environment is not created through policy or terminology.

It is created through presence.

Trauma-informed practice is felt — in the nervous system — before it is understood in the mind.

It is relational, embodied, and based in how we show up, not in what we say.

This is the foundation of the TRUST Framework, developed through lived experience, practice, relational repair, nervous system science, and person-centred values.

It is a way of being with people.

At A Positive Start CIC, we understand trauma-informed support as relational, embodied, and grounded in presence.

It cannot be rushed.

It cannot be forced.

It cannot be faked.

Safety is not stated.

It is felt.

This is why we use the TRUST Framework — a relational model for creating spaces where people feel grounded, emotionally safe, seen, and held.

The TRUST Framework

| Letter | Meaning |

| T -

Trigger Recognition |

Noticing signs of activation in ourselves or others. |

| R- Reassurance |

Offering steady, grounded co-regulation when emotions rise. |

| U- Understanding | Exploring with curiosity rather than judgement or analysis. |

| S -

Safety |

Creating a space where the nervous system can soften, pause, and breathe. |

| T-

Truth |

Congruence: our tone, words, pace, and presence align. |

We do not apply TRUST — we embody it.

Tick-Box Trauma-Informed vs Authentic Trauma-Informed

Many spaces now use the language of trauma-informed practice — but language is not enough.

Tick-Box Trauma-Informed Sounds Like:

- “We are trauma aware.”

- “This is a safe space.”

- “We understand.”

But the body feels:

- Pressure

- Performance

- Emotional hurry

- The sense that your feelings have a time limit

Words without presence do not create safety.

Authentic Trauma-Informed Practice Feels Like:

- Slowness

- Softening

- Permission to pause

- No pressure to speak

- A steady nervous system you can lean into

Most people can feel the difference immediately, even if they cannot explain why.

This is Neuroception — the nervous system constantly scanning:

“Am I safe here?”

“Is this person safe?”

“Can I soften?”

Safety is felt first.

Understanding comes later.

We are energy before language.

Safety and truth are experienced first in the body, not in the mind.

We may smile politely in response to someone’s words,

but the nervous system recognises when the emotional tone does not match the language.

We feel congruence.

And we feel when something is out of alignment.

The body is always telling the truth — long before the mind knows how to articulate it.

If we are unaware of our own nervous system state as practitioners, therapists, or facilitators, we may genuinely believe we are offering safety, empathy, and presence — while our tone, body language, or energy communicates something very different.

A dysregulated or defended nervous system can say all the right things yet still transmit unease.

When we are not connected to ourselves, others cannot feel fully safe connecting to us.

This is often why a person may appear calm, kind, or professional — yet something still doesn’t feel right.

It isn’t about fault or intention.

It’s about regulation, awareness, and congruence.

The nervous system reads authenticity faster than words.

This is why self-awareness and regulation are at the heart of trauma-informed practice —

because the body knows whether safety is genuine.

When Trauma Leaves Us Unanchored

For those who live with Post Traumatic Stress or complex trauma:

- The body may feel unsafe even when nothing is wrong.

- The world may feel unpredictable.

- The self may feel distant.

It can feel like:

being adrift at sea without a raft, without land, without a horizon.

In those moments, asking someone to “self-regulate” is not only unrealistic — it is unkind.

This is where Co-Regulation Matters

We lend our calm.

They borrow our safety.

The body remembers through us.

We do not regulate others by instruction.

We regulate others by presence.

This is why how we are inside ourselves matters more than anything we do externally.

Rebuilding Trust — Slowly, Gently, Over Time

Trauma interrupts trust:

- Trust in others

- Trust in the world

- Trust in oneself

Trust is not restored by being told it is safe.

It is restored by experiencing safety, again and again, in small, repeated, dependable ways.

There was once a guiding principle in youth rehabilitation that young people would learn emotional regulation, dignity, and citizenship through consistent contact with attuned, respectful adults modelling regulation and relational repair.

Where that principle was practiced with compassion and presence, young people gained something invaluable:

A nervous system shaped by gentle, stable co-regulation.

We learn safety inside safe relationship.

Honouring Worth — Our Own and Others’

Trauma often teaches a person:

- to apologise for existing

- to quiet their needs

- to believe they are “too much”

- to shrink themselves to take up less space

A trauma-informed space restores:

- dignity

- permission

- presence

- voice

Honouring worth means:

- Your feelings make sense.

- Your needs are valid.

- You do not have to earn belonging.

And equally:

We honour our own worth by being boundaried, steady, and human — not self-sacrificing.

No one has to disappear for another to be held.

Person-Centred Foundations: The CUE Principles

TRUST is rooted in Carl Rogers’ Person-Centred Approach, based on the three core relational conditions required for growth:

| Principle | Meaning | Why It Matters in Trauma-Informed Work |

| C -Congruence | Being real, honest, and present | The nervous system recognises authenticity before words |

| U-Unconditional Positive Regard | Valuing the persons inherent worth | Worth is often the deepest injury trauma leaves behind |

| E -Empathic Understanding | Understanding experience from inside the person’s world | Trauma is not healed through explanation, but through being felt with |

These are not skills — they are ways of being.

When CUE is present:

The breath deepens.

The body softens.

The self returns.

This is Safety.

This is Truth.

This is TRUST.

Remember;

Without truth - there can be not trust,

Without trust - there can be no emotional safety,

Without safety - healing doesn’t happen.

Free Resource: Trauma Informed TRUST Framework

Download at:

https://apositivestart.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Free-Resource-Trauma-Informed-TRUST-Frameworkpdf.pdf

Facilitator Preparation: Begin With Yourself

Before holding others, ask:

- Am I grounded?

- Do I have space inside myself today?

- Can I allow silence?

- Can I stay present if emotion rises?

If not — we pause.

Regulation comes before facilitation.

Free Resource: TRUST Facilitator Worksheets

Download at:

https://apositivestart.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/TRUST-Facilitator-worksheets-pdf.pdf

A Closing Word

Trauma-informed practice is not about knowing the right language.

It is about offering the right presence.

When we slow down, remain steady, and hold truth gently —

the nervous system finds safety

the self comes home

and healing becomes possible.

This is TRUST.

This is relational care.

This is trauma-informed practice at its core.

With warmth, steadiness, and compassion 🙏

Empathy Will Save Humanity

Why Feeling Deeply Is Not a Weakness, but Our Greatest Intelligence

“The death of human empathy is one of the earliest and most telling signs of a culture about to fall into barbarism.”

— Hannah Arendt

We are living through a time where empathy is being dismissed, numbed, and in places actively discouraged. Sensitivity is called weakness. Depth is labelled dramatic. And those who feel the suffering of others are often told to “toughen up.”

But empathy is not the problem.

The absence of empathy is.

Empathy is the ability to feel with another person — to sense their emotional reality as if touching it with your own hands.

It is connection.

It is conscience.

It is humanity.

When empathy dies, cruelty becomes normal.

And we are seeing this, increasingly, in our systems, institutions, politics, and culture.

But empathy has not disappeared.

It is held by those who refuse to go numb.

What Empathy Truly Is

Empathy is not simply emotional.

It is neurological, relational, somatic, and moral.

It lives in:

- the vagus nerve

- the social engagement system

- the body’s capacity to remain open in the presence of emotion

People who feel deeply are not “over-sensitive.”

They are accurately attuned.

Their nervous system is awake.

Their mirror neurons function.

Their humanity is intact.

This is not fragility.

This is intelligence of the highest kind.

Why Some People Feel Deeply and Others Don’t

Every human is born capable of empathy.

But the nervous system learns from experience.

When a child is responded to:

- with warmth

- attunement

- and emotional presence

Their system learns:

“It is safe to feel.”

But when a child is:

- ignored

- shamed for crying

- mocked for sensitivity

- raised around threat or emotional chaos

Their system learns:

“Feeling is dangerous. Shut it down.”

So some adults stay open.

Others disconnect to survive.

Indifference is not always cruelty —

but when indifference becomes culture, harm follows.

Highly Empathic People: The “Wounded Healers”

People who carry deep empathy are often those who, at some point, were hurt.

They:

- learned to attune to others to stay safe,

- developed sensitivity to emotional shifts,

- understood pain intimately.

And instead of becoming hardened —

they chose to remain open.

This is courage.

This is resilience.

This is leadership.

But those with high empathy are often the first to be dismissed, shamed, or ridiculed by those with low empathy — because empathetic people cannot be controlled.

They:

- question injustice

- speak up where others stay silent

- refuse to dehumanize others

Their conscience cannot be switched off.

And that threatens systems built on dominance, extraction, or power-over.

Why Empaths Need Boundaries

Empathy without boundaries becomes:

- burnout

- emotional overload

- self-sacrifice

Boundaries transform empathy from self-erasure into strength.

A boundary says:

“I can care for you without abandoning myself.”

This is where empathy becomes sustainable —

where compassion does not require collapse.

How Childhood Trauma Shapes Empathic Sensitivity

Many empaths became sensitive because, as children, they had to.

They learned to:

- sense danger in tone, silence, or shift of mood

- anticipate emotional weather

- soothe others to maintain peace

What was once survival later becomes:

- intuition

- emotional wisdom

- deep compassion

- the ability to sit with others in their pain

But the child who learned to feel everything must learn, in adulthood, not to carry everything.

This is where regulation enters.

For some of us, this sensitivity began very young. Not because we were encouraged to feel, but because our emotional world became intertwined with the emotional world of others before we had language for it.

When a child sees fear, panic, or distress in the adults around them — especially in response to their own pain — the child learns, “My feelings impact others. I must be careful. I must monitor. I must attend.” Empathy, then, becomes fused with responsibility. We don’t just feel others — we feel for them, and often instead of them.

This early enmeshment can shape a lifetime of emotional scanning, caretaking, and internalising the belief that our role is to manage the emotional climate for everyone else.

Healing is the slow, compassionate process of untangling this: reclaiming empathy as connection, not burden.

How to Stop Absorbing Others’ Emotions

Empaths do not need to feel less.

They need to feel differently.

- Noticing what belongs to you

- Releasing what is not yours

- Regulating the nervous system daily

- Staying connected without merging

This is the shift from:

carrying someone

to

accompanying them.

Empathy, Emotional Regulation & Children

Empathy is impossible without regulation.

A regulated nervous system can:

- stay open while feeling

- stay connected during stress

- respond with care rather than react with fear

Children who learn emotional regulation early grow into adults who:

- treat others with dignity

- maintain healthy relationships

- communicate clearly and kindly

- recover from stress more easily

- live longer, healthier lives

This is not soft parenting.

This is foundational human development.

Which is why emotional education must be accessible from early childhood.

The River Room Songbook

Emotional Regulation Through Music, Rhythm, Breath & Relationship

This understanding led us to create The River Room Songbook, in collaboration with:

- My Body Is My Body (MBIMB)

- and the wonderful Chrissy Sykes

The River Room Songbook is free for all, offering six original, trauma-informed children’s songs that support:

- naming emotions

- recognising sensations in the body

- calming the nervous system

- expressing feelings safely

- returning to connection after overwhelm

Each song includes:

- regulating movements

- breath patterns

- rhythmic actions

- playful, gentle co-regulation cues

Because music regulates the nervous system faster than words ever will.

To request more information about River Room Songbook & the course - please contact us - info@apositivestart.org.uk

The companion course teaches:

- the neuroscience behind regulation

- how music heals the nervous system

- how adults can co-regulate children in daily life

This is emotional literacy, delivered with joy.

Empathy as Cultural Resistance

We are living in a culture that profits from numbness:

- If people feel, they question.

- If they question, they disrupt.

- If they disrupt, systems must change.

Empaths interrupt harm by refusing to detach.

They:

- refuse to abandon conscience

- refuse to dehumanize others

- refuse to normalize cruelty

They are the counter current.

The quiet revolution.

The keepers of humanity.

In a culture that often rewards:

- disconnection over compassion,

- efficiency over presence,

- image over integrity.

Empathy refuses:

- cruelty,

- exploitation,

- and dehumanisation.

Empathy is not passive.

It is revolutionary.

A Personal Knowing: The Dream of Light and Dark

For many years — long before I had language for any of this — I used to have a recurring dream.

A nightmare, really.

It was always the same:

A vast battle between light and dark.

Not in a cartoon way, but in a way that felt cosmic, ancient, and deeply human.

A struggle for the soul of the world.

In the dream, the darkness almost consumed everything.

Right up to the last moment.

And I would find myself praying in my sleep, with every ounce of strength I had, for the light to hold.

And each time — just as it seemed all was lost —

the light prevailed.

Quietly.

Gently.

Undeniably.

I did not understand it then.

I only knew I woke reverberating with exhaustion and truth.

Looking back now, I see that my mind and body were processing something real — something I could sense but could not yet name:

The world has always been in a conflict between:

- empathy and numbness,

- connection and control,

- humanity and the absence of it.

What I dreamed as a young woman is what we are living now.

But the dream never ended in destruction.

It ended in remembrance.

The light didn’t “win” through force.

It simply refused to disappear.

That has always stayed with me.

It still does now.

The Ongoing Battle: Power Without Empathy vs Power Rooted in Humanity

There is a quiet, constant tension in the world between:

- those who lead through connection, and

- those who lead through control.

Empathy-Based Power (The Light)

People high in empathy:

- collaborate rather than compete

- uplift rather than dominate

- consider others and the collective impact

- act with conscience and responsibility

Their power is relational.

It does not require fear to be effective.

They believe:

“We rise together.”

Control-Based Power (The Dark)

People disconnected from empathy often:

- pursue gain at the cost of others

- require hierarchy to feel secure

- value dominance over connection

- avoid vulnerability because it feels unsafe

Their power requires:

- silence

- fear

- compliance

They believe:

“For me to win, someone else must lose.”

This dynamic is not about good people vs bad people.

It is about nervous system survival strategies.

Some people shut down empathy because, in childhood:

- feeling was punished

- emotions were overwhelming

- safety was conditional

So numbness became armour.

Control became protection.

But armour is not strength — it is unmet pain.

Why Empaths Are So Often Targeted

Empathy:

- exposes harm

- interrupts exploitation

- challenges power without conscience

So highly empathic people are often:

- shamed (“you’re too sensitive”)

- dismissed (“you’re overreacting”)

- mocked (“don’t be so emotional”)

- exhausted with responsibility (“can you just…?”)

Because:

A grounded empath cannot be manipulated.

And that is deeply threatening to systems built on fear and dominance.

The Light and the Dark Are Not Enemies

The “dark” is not evil — it is pain without witness.

The “light” is not perfection — it is presence without armour.

Empaths are not here to fight the dark.

They are here to transform it through relationship, regulation, and truth.

This is the cultural turning point we are living through now.

The Wounded Healers Will Lead Us Forward

Those who have known pain and chosen compassion are the ones who will shape the future.

They do not lead with power.

They lead with presence.

With truth.

With care.

Their empathy is not fragile —

it is forged.

Empathy will save humanity.

Not in theory —

in everyday lived practice.

One regulated nervous system at a time.

One child at a time.

One act of courage to stay open.

We begin here.

Why Mindfulness Can Be Triggering for Trauma Survivors

This is a personal theory supported by trauma research…

Mindfulness, meditation and stillness practices are widely recommended for emotional well-being, anxiety, stress and mental health. They are used in therapy rooms, schools, GP practices, yoga studios and community programmes. And for many people, these practices are genuinely supportive.

However, it has been my experience—both personally and in my work with clients who have Post-Traumatic Stress and Complex Post-Traumatic Stress—that mindfulness is not always safe to introduce. In some cases, it can be deeply triggering and even retraumatising.

This has led me to a theory, which I offer gently and with curiosity:

For people who have experienced trauma, the act of being still, silent, and inwardly focused can resemble the physiology of the freeze response that occurred during the trauma itself.

And if the environment of the original trauma involved silence, immobility, helplessness, dissociation, or being unable to speak or move (which is extremely common), then mindfulness may unintentionally pull a person back into the bodily memory of terror.

During a traumatic event, especially one the nervous system could not escape:

- The breath becomes shallow or holds.

- The muscles become still.

- Awareness narrows inward.

- Speech disconnects.

- The body freezes while waiting for danger to pass.

These are the same conditions often encouraged in mindfulness:

- “Sit still”

- “Notice your inner world”

- “Be quiet and present”

- “Let go of thought”

- “Don’t move”

So instead of peace, the survivor’s nervous system may experience:

- Flashbacks

- Panic

- Emotional flooding

- Dissociation

- A sense of being trapped inside their own body

Not because they are “doing mindfulness wrong.”

But because their nervous system is doing what it learned to do to stay alive.

There Is Evidence to Support This!

Although this is my lived observation and practice-based theory, it is also aligned with established trauma science:

- Polyvagal Theory (Stephen Porges) explains that the body returns to states it associates with survival when certain conditions are recreated.

- The Body Keeps the Score (Bessel van der Kolk) demonstrates how trauma is stored somatically, not cognitively.

- Trauma-Sensitive Mindfulness (David Treleaven) documents how meditation can retraumatise survivors if used before safety is established.

- Ruth Lanius, MD has shown in neuroimaging studies that stillness and internal focus can activate traumatic memory networks.

So while mindfulness can be extremely beneficial after regulation skills are developed, introducing it too early can be harmful.

Over time, I have learned that I can often understand the level of unresolved trauma in a client by noticing:

How long they are able to sit still, quietly, with themselves—without anxiety, panic, dissociation, or emotional overwhelm.

This is not a test.

It is not a judgment.

It is simply information.

Stillness tolerance is a nervous system indicator.

Clients who have lived in prolonged survival states are often:

- Restless

- Activated

- Unable to tolerate silence

- Uncomfortable turning inward

- In motion even when seated (foot tapping, shifting, avoiding eye contact)

This is not resistance.

This is their body protecting them.

Because for them, stillness once meant danger.

I noticed this very clearly when I used to meet clients at a local Priory.

We would begin in the coffee shop — a comfortable, neutral space where quiet conversation could happen naturally. There was movement, background noise, warmth, and the simple safety of being around others without being exposed.

But when I gently invited clients to walk through the Priory afterwards, a pattern emerged.

Almost every time, within a few minutes of stepping into the vast quiet stillness of the Priory, I would see the same responses:

- a leg beginning to shake rapidly

- fingers, nails or skin — biting or picking without awareness

- twirling or pulling at hair

- breathing becoming shallow, held, or heavy

- eyes scanning corners, shadows, exits

- tears rising suddenly

- or an urgent need to leave the building

Their bodies were not responding to the Priory itself.

Their bodies were responding to what the stillness represented.

In many traumatic experiences, survival involves:

- holding breath

- holding still

- going quiet

- freezing and waiting

So when the nervous system encounters stillness, silence, or spacious quiet, it can interpret it as:

“This feels like then.”

“We are not safe.”

This is not avoidance, lack of motivation, or “not being ready.”

It is cortisol and adrenaline flooding the system — the body protecting itself the way it once had to.

So we learned to walk instead.

Movement helped regulate what silence activated.

Safety came through rhythm, pacing, and presence — not stillness.

What looked like “fidgeting” was actually:

The body remembering.

The body protecting.

The body surviving.

And it made complete sense.

There are times when stillness isn’t just uncomfortable — it’s unbearable. For some of us, the nervous system needs movement in order to settle at all.

I learned this in my own healing. I used to cycle through town at a speed that, looking back, could probably have earned me a medal or two if I’d cared to train for it. But I wasn’t cycling for fitness or achievement — I was cycling to survive. The movement burned through the adrenaline, cortisol, and fear that my body had never been able to release. I didn’t know it at the time, but I was instinctively doing exactly what my nervous system needed.

So when I began to notice the same patterns in clients — the restlessness, the panic, the inability to sit still in silence — I started offering bikes. Not as exercise, but as regulation. Cycling in nature gives the body somewhere to put the energy that stillness activates. The rhythm of pedalling, breath, air, ground, landscape — it allows the survival energy to move through instead of stay trapped.

We still offer bikes to clients who want them — and it continues to have remarkable success.

Because for many, healing begins with movement, not stillness.

When we stay truly present with someone — actively paying attention, remaining curious, and holding space rather than becoming afraid of their emotional expression and closing them down — the nervous system receives a very different message. It says:

“You are allowed to exist here. Your feelings make sense. You are not too much.”

It is not the technique that heals, but the quality of presence in the moment of activation.

So When Does Mindfulness Become Safe?

After:

- Education about trauma and the nervous system

- Building emotional literacy

- Creating relational safety

- Practicing grounding with movement, sound, pacing, and breath

- Developing the ability to return to safety after activation

Then — mindfulness becomes something different:

Not re-entry into fear,

but a return to self.

Not freeze,

but presence.

If This Resonates With You

Please know:

➤ You are not failing.

➤ You are not broken.

➤ You are not “bad at mindfulness.”

➤ Your body is protecting you the best way it knows how.

There is nothing wrong with you.

There is something right with your system — it learned how to survive.

Mindfulness may still become a helpful resource for you.

But not by forcing stillness.

Only after safety is reclaimed.

And safety is built, not instructed.

The following works have contributed to the evidence, understanding, and clinical grounding that support this perspective:

Bessel van der Kolk (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma.

Viking.

— Demonstrates that trauma is stored somatically and can be retriggered when internal states resemble past threat.

Stephen W. Porges (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation.

Norton.

— Explains how the nervous system automatically shifts into survival states based on perceived threat, including freeze.

David A. Treleaven (2018). Trauma-Sensitive Mindfulness: Practices for Safe and Transformative Healing.

Norton.

— Provides evidence that traditional mindfulness can retraumatise survivors if introduced before regulation capacity is established.

Ruth A. Lanius, Eric Vermetten & Clare Pain (Eds.) (2010). The Impact of Early Life Trauma on Health and Disease: The Hidden Epidemic.

Cambridge University Press.

— Neuroimaging evidence showing how stillness and inward attention can activate traumatic memory networks.

Peter A. Levine (1997/2015). Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma.

North Atlantic Books.

— Details how freeze and immobilization are survival-based states stored in the body, not psychological weakness.

Pat Ogden & Janina Fisher (2015). Sensorimotor Psychotherapy: Interventions for Trauma and Attachment.

Norton.

— Explains why internal awareness practices must be paced slowly for trauma survivors, to avoid somatic overwhelm.

Benjamin Fry (2018). The Invisible Lion.

Harper Thorsons.

— Metaphor of the invisible lion to describe ongoing nervous system threat perception when no danger is physically present.

Janina Fisher (2021). Transforming the Living Legacy of Trauma: A Workbook for Survivors and Therapists.

PESI Publishing.

— Shows how trauma-based shame becomes an internal identity, reinforcing survival responses.

Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the Body: A Sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy.

Norton.

— Demonstrates how internal focus can trigger stored somatic memories if not supported by grounding and attunement.

Lanius, R., Frewen, P., Vermetten, E., & Yehuda, R. (2010). Fear Conditioning and Early Life Trauma.

Oxford University Press.

— Explores how the nervous system learns to associate internal states with threat.

Additional Research on Difficult or Adverse Responses to Mindfulness

Willoughby Britton et al. (2019). Can Mindfulness Be Too Much of a Good Thing?

Brown University / Cheetah House Research.

— Examines dissociation, panic, and trauma resurfacing during meditation.

Lindahl, J.R., Fisher, N.E., Cooper, D.J. et al. (2017).

The Varieties of Contemplative Experience: A Mixed-Methods Study of Meditation-Related Challenges.

PLoS One, 12(5).

— Documents that meditation can activate traumatic memory and emotional overwhelm.

The Nervous System Isn’t Asking Your Permission

It is almost impossible to fully convey the impact of nervous system activation to someone who has never experienced it. What may look, from the outside, like being “over-sensitive,” “attention-seeking,” or “childish” is, on the inside, a state of terror.

The person is not reacting to the present moment as others see it — they are reacting to something their nervous system has recognised from the past as dangerous.

The threat may be invisible to others, but it is completely real to the person experiencing it.

Benjamin Fry describes this powerfully in The Invisible Lion:

When someone has been through trauma, it is as if there is a lion in the room that nobody else can see.

The nervous system remembers.

It reacts as though the threat is happening again — even when the rational mind knows it isn’t.

This is where the internal conflict begins:

- The thinking brain says “I should be fine.”

- The survival brain says “I am not safe.”

Outside, everything appears calm.

Inside, the system is in alarm.

This disconnection can be deeply confusing and disorientating.

Because no one else is running, shouting, freezing, shaking, or crying, the person often turns the fear inward:

“What’s wrong with me?”

instead of the far more accurate:

“What happened to me?”

Where Shame Enters

For many with complex trauma, this internalisation began long before adulthood.

If you grew up hearing — spoken or unspoken — that:

- Your emotions were “too much”

- Your needs were “inconvenient”

- Your reactions were “dramatic”

- Your pain was “exaggerated”

then it becomes easy, even automatic, to believe:

“The problem is me.”

Not the circumstances.

Not the environment.

Not the trauma.

Just me.

The body remembers fear.

The mind remembers shame.

And when the nervous system becomes activated later in life, the shame does not calm the system —

it intensifies it.

Shame adds another layer of threat inside the body.

Shame says:

- “You’re weak.”

- “You’re failing.”

- “You should be past this.”

- “Everyone else manages.”

And so the trauma cycle continues:

- A trigger activates survival mode.

- The body reacts.

- Shame interprets the reaction as proof of being “broken.”

- The reaction worsens.

- The person blames themselves.

This is not pathology.

This is adaptation.

The nervous system learned to protect life in an environment that did not feel safe.

The behaviour is not the problem.

The environment that shaped it was.

So, What Is Trauma?

Trauma is an overwhelming experience that the nervous system could not resolve or process at the time.

What Is Post-Traumatic Stress?

It is that overwhelming past experience being re-activated by similar dynamics in the present.

The survival system is doing exactly what it was designed to do — protect life — but now out of context.

This means:

- The fear is real to the body.

- The brain is in survival mode.

- Reasoning, communication, and emotional regulation are hijacked.

- The person is not choosing their reaction — they are being carried by it.

From the outside, it may look irrational.

We even have shaming labels for it:

- “Throwing a tantrum”

- “Spitting the dummy”

- “Acting like a child”

But from the inside, it feels like:

- A siren has gone off in the body.

- The mind is flooded with alarm.

- The person is trying to survive something no one else can see.

Healing does not mean the fear was never real.

It means the nervous system finally found safety.

The Real Question Is Not:

“Why are they behaving like that?”

The Real Question Is:

“What danger does their nervous system believe is present?”

And then:

Can we meet that moment with compassion instead of judgment?

When You See a “Big Reaction” — Pause

The next time you witness what looks like:

- “Attention-seeking”

- “Overreacting”

- “Being dramatic”

- “Oversensitive”

Pause.

Ask:

“What am I really witnessing here?”

Could this be survival mode out of context?

Chances are, it is.

And the real solution is not discipline, dismissal, or correction.

The real solution is safety.

T R U S T

A trauma-informed relational framework:

T — Trigger Recognition

See what is happening beneath the behaviour.

It’s not attention-seeking — it’s attention-needing.

R — Reassurance

Calm presence regulates more than any instruction ever will.

U — Understanding

What looks irrational on the outside often feels life-or-death on the inside.

S — Safety

Safety is communicated through relationship, tone, proximity, breath, warmth, pacing.

T — Truth

“You’re not in danger now. I’m here with you. You are safe.”

This is how we stop reacting to the behaviour and start responding to the nervous system.

This is how we replace shame with understanding.

This is how we create connection where there was once fear.

This is how healing begins.

Ask about of Free Trauma Informed TRUST training and resources - advocating for a Trauma informed society

What Looked Like Nothing, Felt Like Everything

A reflection on trauma responses people don’t see

Years ago, I had just started a new job — I’d only been there about a week. One day, I went off to a meeting elsewhere in the building. When I came back, the office I usually worked in was completely closed. The lights were off, the door was locked, and no one was there.

I hadn’t expected that.

No one had mentioned anything to me.

It turned out that everyone had gone to work in a different office for the afternoon. For them, this was normal — something that happened occasionally. But I was new. I didn’t know this was something that could happen. And no one realised I didn’t know.

From the outside, it was a small, ordinary oversight.

But inside my body, something much bigger began.

My stomach tightened. My chest grew warm. My mind started racing, trying to make sense of what I was seeing. There was no threat in the room — there wasn’t even anyone in the room — yet my nervous system reacted as though I was suddenly unsafe.

This was a trauma response.

Not to the situation itself, but to what similar situations had meant in my past:

“You’ve been left out.”

“You don’t belong.”

“They didn’t think to include you because you’re not wanted.”

None of those thoughts were based in the present moment —

but they were loud, familiar, and believable.

Because our bodies remember what our minds have long tried to move past.

And in the past, I would have acted from that place.

I would have left the building.

Or shut down.

Or convinced myself I’d made a mistake in ever thinking I belonged there.

I might even have resigned — just to avoid the pain of feeling unwanted.

And from the outside, it would have looked like I was being:

- overly sensitive,

- dramatic,

- childish,

- or attention-seeking.

Because that’s all you can see if you only see the behaviour.

But inside, it was survival.

This is the part many people never realise:

| What Others Saw | What I Was Experiencing Internally |

| A new colleague working quietly | A nervous system in full activation |

| A harmless oversight | A perceived threat to belonging and safety |

| Nothing happening at all | A resurfacing of old wounds and memories |

We were in the same environment, but we were living completely different realities.

How can two people be in the same moment but living two completely different realities — and neither one is wrong?

That question changed everything.

Because this time, something was different.

I noticed the response as it happened.

I was able to say to myself:

“This feels like rejection, but that doesn’t mean it is rejection.”

The feelings were real.

The fear was real.

The physical response was real.

But the story attached to them was old.

So instead of running, hiding, or shutting down,

I stayed with myself.

I breathed.

I walked slowly.

I let the sensations rise and fall, without making them into a conclusion.

Later, when I rejoined the others, I saw the truth:

There was no tension.

No avoidance.

No shift in tone.

No hidden meaning.

No one was thinking about me at all — and not in a painful way, but in an ordinary way.

They genuinely hadn’t realised.

There was no exclusion.

No judgement.

No rejection.

It was simply a moment I interpreted through the lens of my past.

And in that moment, I saw something essential:

People cannot respond to what they cannot see.

They didn’t know what my nervous system was holding.

And I didn’t need to blame them.

Because the healing didn’t come from others behaving differently.

The healing came from me recognising the story as it emerged — and choosing not to follow it.

Why This Matters

This is why trauma-informed understanding is so important.

Not to analyse each other.

Not to tiptoe around one another.

But to remember:

Behaviour is not the whole story.

A person who goes quiet may not be shutting people out —

they may be holding themselves together.

A person who steps away may not be being rude —

they may be trying not to collapse.

A person who “seems fine” may be fighting an entire internal storm that no one can see.

When we understand this,

we stop asking:

“Why are they acting like that?”

and begin asking:

“I wonder what this moment might feel like for them?”

That is where compassion lives.

That is where connection becomes possible.

That is where belonging begins — not in being included, but in being understood as human.

Professional Insight: What This Teaches Us About Healing

Understanding this experience has shaped how I support others.

When I realised my reaction was a nervous system response rather than a personal failing, my entire perspective shifted. I stopped viewing behaviours like withdrawal, shutdown, emotional overwhelm, or silence as “overreactions” — and started recognising them as the body’s way of trying to stay safe.

This matters, because when someone is triggered:

- They are not choosing to react.

- They are not being dramatic.

- They are not being difficult.

- They are responding to something that once protected them.

The nervous system remembers experiences long after the mind thinks they have been resolved.

And once we understand that, our role changes:

| Before | After |

| Why are they acting like this? | What is their nervous system trying to protect them from? |

| Trying to reason someone out of their feelings | Supporting regulation and safety first |

| Interpreting behaviour personally | Understanding behaviour as adaptation |

| Responding to the story | Responding to the state |

This insight is foundational to trauma-informed practice:

Regulation comes before reasoning.

Safety comes before insight.

Compassion comes before intervention.

When we meet people at the level of the nervous system, rather than the level of behaviour, we create the conditions for healing instead of shame.

For me, staying in that moment — not running, not abandoning myself — became living proof that healing is possible.

Not because the trigger disappeared, but because I didn’t disappear when it came.

And that is where trauma begins to lose its power.

That is where belonging begins.

Inside the body — not in the behaviour of others.

In Closing

So I return again to this question, because it changed me:

How can two people be in the same moment but living two completely different realities — and neither one is wrong?

We don’t need to agree on the reality.

We only need to remember there may be more than one.

When we hold space for that,

we make room for compassion — for ourselves and each other.

And slowly, gently, we learn to stay.

Beyond Blame: Understanding Incel Identity Through Attachment, Not Outrage

There is a growing concern in education, safeguarding, and mental health fields about the influence of figures like Andrew Tate and others who appeal to boys and young men. It can feel easy — and even comforting — to say the problem starts with these influencers. But when we place the blame solely on external personalities, we risk missing what is actually happening beneath the behaviour.

The incel identity, and the behaviours associated with it, do not begin with ideology.

They begin with pain.

They begin with attachment wounds — the parts of a young person that did not feel chosen, secure, mirrored, supported, encouraged, or understood when they most needed to be. Influencers do not create that wound. They simply give language to it. They speak into the ache.

And when a young person finally hears someone name their hidden shame or loneliness — even in a distorted way — it can feel like belonging.

This is why arguments, lectures, and blame rarely shift these identities.

They speak to the behaviour, not the wound beneath it.

A Shame-Based Identity, Not Defiance

Many young people drawn into incel thinking have experienced:

- Emotional neglect (even in caring families)

- Repeated feelings of rejection or invisclusion

- Difficulty forming social or romantic connections

- A lack of emotionally present male role models

- Limited emotional language or space to talk about loneliness

The result is shame — the sense of “I am not wanted as I am.”

Shame is unbearable to sit with alone.

So the psyche builds a defence:

“The problem is not me. The problem is women. The problem is society. The problem is everyone else.”

This is not arrogance.

This is protection.

It is the nervous system trying to survive emotional pain.

The Self-Awareness Scale

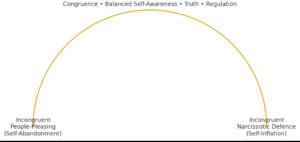

We can understand this more clearly by looking at the Self-Awareness Scale:

- On one end of this scale, we find people-pleasing — the collapse of the self to gain approval.

- On the other end, we find narcissistic defence — the inflation of the self to avoid shame.

- In the centre is congruence — the grounded ability to remain connected to oneself and others at the same time.

We all move along this scale.

No one is fixed to one end.

This is not about diagnosing, labelling, or blaming.

It is about recognising:

- what our protective patterns are,

- what they are protecting us from,

- and how they impact the relationships around us.

Self-awareness is the goal.

Not perfection. Not performance.

Just the gentle capacity to notice ourselves.

Why Blame Makes Things Worse

When educators, parents, or professionals respond to incel thinking with:

- Shaming

- Ridiculing

- Moralising

- Outrage

we recreate the same relational injury that led to the identity in the first place.

If the wound is shame, and we respond with shame, the wound deepens.

If the defence is “I am unsafe with others,” and we respond with hostility, we prove the defence right.

Blame recreates the very dynamics that caused the wound.

To teach congruence, we must model it.

What Helps Instead?

Young people heal through:

- Attuned relationship, not correction

- Curiosity, not confrontation

- Emotional language, not embarrassment

- Grounded adult regulation, not adult frustration

- Belonging, not behavioural compliance

We must be the calm nervous system they can borrow from until they learn to regulate their own.

This is the heart of trauma-informed safeguarding.

A Final Reflection

The word education comes from the Latin educare and educere —

meaning to draw out from within, not to impose from the outside.

Our role is not to fix, shame, frighten, or force young people into maturity.

Our role is to help them meet themselves — with dignity, safety, truth, and compassion.

Because when a young person feels seen, valued, and accepted, they no longer need armour to be in the world.

It’s Not “Attention Seeking.” It’s a Nervous System in Survival.

Across education, social care, healthcare, policing, and even politics, there is still a widespread misunderstanding of trauma. Behaviours rooted in survival are often misinterpreted as:

- “Attention-seeking”

- “Manipulative”

- “Excuses”

- “Lack of discipline”

- “Bad attitude”

And those of us who respond with compassion are sometimes seen as soft, naïve, dismissed as ‘snowflakes’ or too forgiving.

But here is a truth many have not yet been taught:

Trauma is not psychological misbehaviour.

It is a nervous system doing its best to stay alive.

Before we go any further, we need to ask one essential question:

What does this behaviour bring up in us?

Because when we see someone dysregulated, chaotic, overwhelmed or reactive — our own nervous system responds too.

If we feel:

- Challenged

- Threatened

- Disrespected

- Out of control

…we might react from our own discomfort, rather than from understanding.

Trauma-informed practice begins here — not with how we respond to the other person, but with how we regulate ourselves in the presence of their dysregulation.

If we cannot stay regulated when someone else is not, we will always default to control, punishment, or withdrawal.

Not because we don’t care —

but because we feel overwhelmed, too.

When Safety Was Never Learned, Chaos Becomes Home

If someone has experienced adversity from birth, their nervous system did not get the chance to learn:

- Safety

- Trust

- Predictability

- Being comforted

- Being held in distress

There is no internal anchor to return to.

So their default state is not calm.

Their default is chaos.

They may be:

- Easily overwhelmed

- Quick to shut down or explode

- Drawn to chaotic people or environments

- Creating chaos when there is none

Not because they want to.

But because chaos is what their nervous system recognises as familiar and we often mistake familiar for safe.

This is not attention-seeking.

This is attachment injury and survival physiology.

Trauma is not what happens to us — not the event — it’s what happens inside of us as a result of the event. So when someone says “Well I’ve had worse things happen to me and I’m fine. I still manage to hold down a job / stay in class / cope,” it may feel logical to them, but it is not a trauma-informed comparison. Our capacity to cope is shaped long before any “big event” — it is shaped by whether we grew up with a sense of safety or a sense of threat.

Someone who fundamentally believes they are loved, they belong, and they are safe at their very core will experience adversity differently from someone who has grown up believing they are unlovable, unsafe, or alone. One person’s nervous system has an anchor; the other does not. We are not starting from the same internal ground. Comparing the two is like comparing apples and pears — the outside may look similar, but the internal structure is entirely different.

And after all — what we believe is true, because we believe it.

Our nervous system doesn’t respond to “reality,” it responds to perceived reality.

The world we expect is the world we experience.

Punishment Does Not Switch Off the Threat Response

And yet, in so many institutions, punishment is still the primary approach.

Punishment does not regulate.

Punishment intensifies the threat response.

It teaches:

- “I am bad.”

- “I am alone.”

- “I cannot be seen when I am struggling.”

And the cycle continues.

Compassion Is Not Weak. It Is Regulating.

Compassion is not the absence of boundaries.

Trauma-informed practice is:

Support + Structure

Connection + Consistency

Understanding + Accountability

Boundaries are essential.

But boundaries are not punishments.

Boundaries are anchors. They say:

“I will not abandon you.

And I will also not allow harm.”

This is the balance.

We do not remove expectations.

We support people to meet them.

We give:

- Co-regulation

- Predictability

- Clarity

- Tools

- Time

- Patience

- Safe relationship

Because nobody learns in survival mode.