Systemic Exclusion

Over the past few weeks, I’ve been reviewing counselling job listings — often alongside students I support — and I’ve noticed something deeply concerning:

Nearly every role demands the same thing: “Applicants MUST be registered with BACP, BABCP or NCS — full or provisional.”

Some roles go further, insisting practitioners have their own private therapy rooms. While that isn’t universal, the pattern is clear: these jobs are closing the door on skilled, ethical, trauma-informed professionals who have simply chosen not to align with one of these institutions.

As someone with years of experience supporting individuals through trauma and emotional distress, I find this both discriminatory and damaging — not just for practitioners like me, but for the clients who lose access to diverse, deeply attuned support.

When Paper Trumps People

Take this current 0-hours contract listing, offering £38 per hour:

“Applicants MUST have British Association of Counselling and Psychotherapy OR Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP/BACP) OR NCS registration — full or provisional.”

“Applicants MUST have their own therapy premise to provide face-to-face counselling.”

Despite being self-employed, on a zero-hours basis, and offering no job security, the requirements are inflexible and exclusionary. The job asks for a minimum Level 4 Diploma — yet prioritises BACP/BABCP/NCS affiliation over everything else. It excludes highly capable, trauma-informed practitioners who may have advanced qualifications, years of experience, and live community credibility but choose not to register with one of these three bodies.

The listing continues:

“Applicants must have a commitment to safeguarding, managing risk including suicide and self-harm. Must be able to engage using evidence-based theoretical interventions, including CBT and counselling skills. Must demonstrate empathy and communicate sensitively.”

And yet — somehow — none of these qualities can count unless you’re a member of BACP, BABCP, or NCS.

This is where the contradiction lies.

If empathy, sensitivity, safeguarding, and ethical communication are truly valued, then the framework for who gets hired should reflect that — not reduce competence to a subscription.

Let’s ask an important question:

What actually makes a good therapist?

Is it BACP registration?

Or is it care, compassion, lived insight, ethical presence, congruence, and the ability to truly see and hold another human being?

Because I’ve seen newly qualified therapists, fresh from academic training, gain automatic credibility based purely on affiliation — despite limited client experience and minimal exposure to trauma. Meanwhile, seasoned practitioners with embodied wisdom and thousands of hours of service are overlooked simply because they don’t wear the “right” badge.

This isn’t about ego or hierarchy. It’s about recognising that healing is relational, and relationships aren’t built with certificates — they’re built with presence.

The Problem With Current Regulation

BACP, BABCP, and NCS may serve a purpose — but they are not the only route to ethical, effective practice.

Requiring registration with only these bodies creates:

- A financial barrier for those from marginalised backgrounds

- A philosophical mismatch for trauma-informed or somatic practitioners

- An exclusion of lived experience as valid professional grounding

- A loss of innovation in therapeutic models that go beyond talking therapy

- A rigid, monocultural lens on what “qualified” means

This is especially harmful when coupled with requirements like having a private therapy space — further privileging those with financial resources and excluding community-based or mobile models of care.

What Regulation Should Look Like?

We do need regulation. But we need regulation that reflects the reality of therapeutic practice, not just institutional allegiance.

A better, more inclusive model would be competency-based and grounded in ethical accountability rather than membership status.

Imagine a framework where therapists demonstrate:

✅ Ethical understanding

With a clear practice statement outlining confidentiality, boundaries, consent, and safeguarding.

✅ Supervision

Regular, reflective supervision with a qualified or peer-reviewed supervisor.

✅ Insurance & accountability

Public liability insurance and a transparent client feedback or complaints process.

✅ Ongoing learning

Evidence of professional development — whether through courses, reflective writing, or lived experience integration.

✅ Lived experience & relational skill

A clear ability to use personal insight safely and ethically in service of the client’s growth.

✅ Client impact

Testimonials or feedback that reflect real-world trust and effectiveness.

This model values how you show up, not just what you’ve paid for.

What We Stand to Lose if We Don’t Change

If current practices continue to dominate, we risk losing:

- Therapists with cultural, somatic, or community-grounded wisdom

- Lived experience practitioners who offer unmatched empathy and attunement

- Innovators working outside medicalised models — using music, nature, movement, or story

- True diversity in therapeutic approaches, especially for those failed by traditional services

We’ll be left with a narrow field — full of box-tickers, but lacking the kind of deeply human support so many people truly need.

A Call for Change

To organisations, employers, and funders:

If your aim is to provide meaningful support — especially for communities impacted by trauma, addiction, or systemic injustice — ask yourself:

Would you rather hire someone BACP-registered, or someone trusted by the people you serve, supervised, insured, and deeply attuned to trauma and healing?

The answer should be: Why not both?

Let’s move toward regulation that recognises multiple valid pathways to practice. Let’s create space for lived wisdom, ethical independence, and diverse forms of healing.

Let’s stop letting paper trump people.

If You’re a Practitioner Feeling Shut Out…

You are not alone.

You are not lesser.

You are not unqualified just because you refuse to pay for permission to do what you’ve already been doing with integrity, compassion, and care.

There is space for your voice — and I’ll keep using mine to help make that space wider.

A Final Note

I refuse to be made to feel less than because I choose a different path.

I know my worth.

I trust my experience.

And I approve of myself.

Accreditation may open some doors — but integrity opens hearts.

And that’s where real healing begins.

From the River Room to the World: Teaching Emotional Regulation Through Song

Teaching emotional regulation to adults is not always easy.

In my work with A Positive Start CIC, I’ve often met adults who instinctively dismiss grounding techniques, breathwork, or vagus nerve activation as “woo woo” or “silly.” They weren’t taught about the nervous system, emotional regulation, or the power of somatic practices. For many, it's hard to see the value of these tools until crisis strikes — by which point, the thinking brain is offline and the tools feel inaccessible.

And then I started noticing something else: The same resistance I saw in adults often showed up in children. Children feeling awkward and uncomfortable. Not because they weren’t open, but because the adults around them weren’t modelling the practices, or didn’t yet know how to teach them in ways that felt natural and safe.

That’s when inspiration struck — at the MBIMB Safer Futures conference, where I was introduced to the incredible work of Chrissy Sykes and her My Body Is My Body campaign. Chrissy was teaching children across the globe about body safety and awareness using song, animation, and movement. It was simple. Joyful. Powerful. And, most of all — effective.

I remember thinking, whilst watching the MBIMB songs play on the screen in front of us and swaying along in time with the music : "This is fantastic, - Could we teach emotional regulation the same way? Could we plant seeds of safety, confidence, and connection through songs that make children feel seen, heard, and held?

That question led to a collaboration between A Positive Start CIC and Chrissy Sykes. Combining our trauma-informed approaches, and building on our River Room project — a safe, creative space where children can just be — we created The River Room Songbook: a growing collection of songs that teach regulation, self-worth, and connection through music, movement, and story.

Because here’s the thing: Waiting until you're in crisis to learn regulation tools is like trying to learn how to swim while drowning. Children — and adults — need to practice these tools before they need them. So that when overwhelm hits, the response is already wired in. That’s why we made the songs fun. Natural. Relatable. So the nervous system learns them through joy, not pressure.

Our Vision for the Future

We dream of a world where the River Room Songbook is taught in schools, nurseries, and communities across the globe — where every single child has access to these life-shaping techniques as and when they need them.

Where it becomes common practice — a natural, default go-to when life gets tough in adulthood.

Because the alternative? Ignoring, suppressing, masking, or avoiding unprocessed emotions — all of which can take a toll on our nervous system health. These unresolved patterns don’t just affect individuals; they ripple outward, impacting families, relationships, workplaces, and entire communities through unconscious, often harmful behaviours.

This approach is especially powerful in supporting children and families living with the effects of complex trauma. Unlike a single traumatic event, complex trauma often involves ongoing stress, relational harm, or instability that can deeply affect the developing nervous system. By integrating emotional regulation techniques early - through music, rhythm, and connection - we help children build safety from the inside out. This creates a foundation for lifelong nervous system balance, reducing the long-term effects of trauma and supporting more connected, compassionate communities.

When we give children the tools early, through joyful, embodied learning, we give them something far more powerful than temporary relief — we give them resilience, awareness, and self-trust.

You can access this free resource here - feel free to share it with family, friends and neighbours The River Room Songbook

From Limpopo to the World… a Song of Worth, Pride, and Healing

We are beyond thrilled to share this incredibly heart-warming moment from Limpopo, South Africa, where a group of extraordinary children are singing “I Am Special”, a brand-new song from The River Room Songbook.

Taught by the dedicated team of Pastor Rose Papola and Zama Buthelezi, through the Girls Empowerment programme (in partnership with My Body is My Body and supported by Rotary International), these children aren’t just learning a song — they’re learning to believe in themselves.

“I Am Special” is more than a melody — it’s an affirmation. It reminds every child: You matter. You are worthy. You are loved.

What began as a gentle, trauma-informed idea in a quiet River Room in Scotland and Yorkshire, has now become a global movement — with songs reaching children in schools, churches, and communities around the world.

In the second part of this video, the children share what they’ve learned — it’s moving, powerful, and a reminder of why we do this work.

This is what music for healing and empowerment looks like. This is how we plant seeds of worth that will grow for generations.

Explore The River Room Songbook here: https://apositivestart.org.uk/the-river-room-songbook/

With love and gratitude to all who are bringing these songs to life — and to every child singing loud and proud: You ARE special. And the world is brighter because of you.

In collaboration with: My Body is My Body Programme – MBIMB Foundation & A Positive Start CIC

https://vimeo.com/1102430621?share=copy

Our Mission

A Positive Start CIC is dedicated to fostering emotional healing, safety, and growth through trauma-informed, person-centred approaches. We provide counselling, psychotherapy, psycho-education, and social-emotional learning (SEL) in both individual and group settings, face-to-face and online. By honouring lived experience and empowering those impacted by adversity, exclusion, or trauma, we help individuals reconnect with themselves and their communities. Through therapy, creative education, peer mentoring, collaborative projects, and community initiatives, we promote nervous system regulation, self-worth, and lifelong resilience—supporting people not only to recover, but to thrive.

Deborah J Crozier – Founder & CEO

We’re All on the Sliding Scale: People-Pleasing, Narcissistic Traits, and the Path to Congruence

It’s easy to label others as narcissistic or manipulative. But what if I told you we’re all on a sliding scale—between people-pleasing on one end and narcissistic traits on the other—and that both ends of this scale reflect incongruence?

They may look different, but they are often fuelled by the same thing: unresolved emotions stored in the body and shaped by survival. Whether we’re constantly trying to keep others happy or blaming everything outside of ourselves, we are not acting from truth—we are acting from protection.

At A Positive Start CIC, we support self-awareness and healing through our RAPPORT framework—a gentle, trauma-informed approach to self-discovery for recovery.

Incongruence at Both Ends

People-pleasing may appear kind or selfless, but when it comes from fear or avoidance, it’s not congruent. It’s a mask.

Narcissistic traits, meanwhile, project blame, deny responsibility, and manipulate through victimhood—another kind of mask.

Both patterns suppress truth, emotions, and responsibility. Both are strategies that often begin in childhood. And both are invitations to heal.

Unresolved Emotions Live in the Body!

We like to think other people “make us feel” certain things. Their behaviour. Their tone. Their choices. But emotional triggers are within us, not outside.

The discomfort lives in the nervous system.

Think of the moment when you mutter, “That stupid bag caught itself on the handle.” That little outburst is familiar for many of us—and it’s a clue. It’s not about the bag. It’s a flash of blame from an overwhelmed system.

Narcissistic traits do the same thing, only more deeply:

- “You made me act this way.”

- “You’re too sensitive.”

- “I’m the one who’s hurt, not you.”

This behaviour avoids internal responsibility. It reacts from pain, not presence. And the truth is: we are all capable of this until we start noticing.

Introducing RAPPORT: Self-Discovery for Recovery

Healing begins when we get curious—not critical—about our reactions. That’s why we use the RAPPORT framework. It’s not a quick fix. It’s a compassionate process of building inner safety, truth, and congruence.

R – Recognise

Notice the pattern. Are you people-pleasing? Are you blaming? Is this moment familiar? Recognition opens the door.

A – Accept

Allow what’s there without judgment. Accepting your emotional response doesn’t mean you agree with it—it means you stop fighting it.

P – Process

Let the feeling move. Breathe. Cry. Talk. Write. Movement. Stillness. Whatever your body needs, let it flow.

P – Practice

Start choosing new ways of responding. It takes time and repetition. Small, consistent shifts matter.

O – Observe

Watch yourself with kindness. Notice when old habits creep in. What helped? What didn’t?

R – Reflect

Ask deeper questions: What was really going on for me? What did I need in that moment? How does this connect to my past?

T – Transform

Transformation isn’t dramatic. It’s subtle, steady, and rooted in truth. It’s choosing congruence over protection, again and again.

The Path to Congruence

We can’t grow out of what we refuse to acknowledge. Blame keeps us stuck. People-pleasing erodes us. But when we start showing up with honesty, fairness, and emotional integrity—we begin to feel safe in our own skin.

No more masks. No more deflection. Just presence.

When we catch ourselves in a blame loop or avoidant pattern, we can pause and say:

“This is mine to feel. This is mine to heal.”

Congruence is the goal—not perfection. When we aim for balance, fairness, truth, and compassion, we know we’re on the right path.

Silence

Over the years, I’ve heard many people say something like this after trying therapy:

“They just sat there and stared at me. I didn’t know what to say. I felt exposed and uncomfortable.”

Often these are people who came for support but left feeling even more alone. And when that happens, something sacred—the trust between client and therapist—can break before it even begins.

This experience is far more common than it should be. And I want to talk about it—not to criticise other therapists, but to shed light on something important:

There’s a huge difference between therapeutic silence and feeling emotionally abandoned.

What is therapeutic silence supposed to do?

In some forms of therapy, especially traditional psychodynamic or psychoanalytic approaches, silence is intentional. The therapist steps back so that the client can access deeper layers of thought, feeling, or unconscious material without interference. The idea is that the space invites reflection or insight.

But this approach doesn’t work for everyone.

For those who carry trauma, relational wounds, or histories of emotional neglect, unattuned silence can feel like re-experiencing those very wounds. Instead of helping them go deeper, it can leave them frozen, hyperaware, or ashamed.

Silence without presence can feel Like absence. Silence itself isn’t the issue. It’s the quality of the silence that matters.

In person-centred therapy, the focus is always the client—not the therapist’s technique, theory, or internal process.

Carl Rogers taught us that the core conditions for healing are empathy, unconditional positive regard, and congruence. These are felt conditions. They’re not just concepts—they are lived, moment by moment, in the presence of another human being.

So when silence occurs in a session, it should serve the client. Not the therapist’s idea of what should happen. Not their discomfort with emotion. Not their silence as a strategy.

If a therapist is silent, it should be because they are deeply with the client—not because they’ve gone inside themselves or defaulted to a model.

The moment becomes about you - the client. Your experience. Your energy. Your pace.

That’s what person-centred work honours.

It doesn’t demand that you perform insight.

It offers you space that’s safe enough for insight to arrive in its own time.

When a therapist is grounded, attuned, and emotionally available, silence can feel deeply held. It can be a moment where both people breathe, where something unspoken is honoured.

But when a therapist remains quiet without offering warmth, presence, or any felt sense of safety, the silence can feel like abandonment.

And the nervous system always knows the difference.

Holding space is not the same as saying nothing. Holding space is an active process. Even without speaking, the therapist is listening deeply—with their body, their intuition, and their heart. They’re noticing subtle cues: posture, breath, energy shifts. They’re connected to the moment.

In contrast, silence that comes from detachment, uncertainty, or theoretical rigidity doesn’t feel safe. It feels cold. Or judgmental. Or indifferent.

And for someone who’s spent a lifetime feeling unseen or misunderstood, this can do more harm than good.

If you’re a therapist, consider this a gentle check-in:

- Are you with the client in your silence?

- Do they know you’re there, emotionally and energetically?

- Can your stillness be felt as care—not as waiting for them to “perform” healing?

Attunement matters. Trauma-aware presence matters. Even in silence, the room should feel relational.

As the client, you deserve to feel safe.

If you’ve had a therapy experience that left you feeling exposed, judged, or abandoned, it wasn’t your fault.

Therapy should never feel like emotional abandonment. You deserve a space where silence feels like safety—not like being left alone with your pain.

Trust your body. If something felt off, it probably was. And there are therapists who will sit with you in a way that feels steady, kind, and present.

Healing happens in the presence of safety. Not forced silence. Not long stares. But felt, relational safety. That’s what good therapy—especially trauma-informed therapy—offers.

We must recognise that survival itself is an achievement.

When we strip everything back to the human, we are hardwired to prioritise survival above all else—that’s the job. The nervous system is not betraying us; it’s protecting us. Every freeze, every shutdown, every hyper-alert moment was your body’s way of keeping you alive, even when connection wasn’t safe.

Whether we speak or sit in silence, the real work is in how we hold one another.

And sometimes, just knowing you’re not alone in the quiet is the most powerful thing of all.

Final Thoughts - The Nervous System Doesn’t Lie!

Healing happens in the presence of safety. Not forced silence. Not long stares. But felt, relational safety. That’s what good therapy—especially trauma-informed therapy—offers.

Whether we speak or sit in silence, the real work is in how we hold one another. And sometimes, just knowing you’re not alone in the quiet is the most powerful thing of all.

Seeing the Same Screen, Reading Different Code

Sometimes the hardest part of communication is not the words themselves, but the way we interpret what we don’t understand.

A family friend once shared how, when trying to communicate with certain colleagues - they felt like their words left their mouth and fell through the floorboards — picking up dust and distortion before landing somewhere else entirely. What they meant and what the other person heard often felt worlds apart.

My son offered a powerful analogy that helped everything make sense - “It’s like you’re both looking at the same thing on a computer. You see graphics. they see text.”

It was a simple yet striking way to describe what happens in communication with someone who has aphasia. You might be sharing the same moment, looking at the same situation, but experiencing it in completely different ways.One person is taking in emotion, tone, and visual cues — like seeing the full graphic interface. The other is reading line by line, processing fragmented information like text that must be decoded.

This story illustrates a broader truth: we often misinterpret what we don’t understand.

When communication feels hard or confusing, we may assume someone isn’t listening, doesn’t care, or is being difficult — when in reality, their brain is simply processing language in a different way.

Aphasia changes how someone communicates, not what they know or who they are. It means the route to understanding looks different. It might require fewer words, more visual support, extended time, or just patience and presence.

When we stop forcing understanding through our own lens, and instead adapt to how someone else receives information, connection becomes possible again.

It’s not about saying less. It’s about saying it in a way that can be received.

Sometimes, the deepest understanding happens in the quiet spaces between words.

I regularly use Dr Dan Siegels Wheel of Awareness mindfulness exercise and have suggested it to others. But how may someone with Aphasia experience the Wheel of Awareness?

The Wheel of Awareness, developed by Dr. Dan Siegel, is a mindfulness tool that guides attention across different aspects of our experience — from our five senses, to bodily sensations, mental activities, and a sense of connection with others.

https://drdansiegel.com/wheel-of-awareness/

For someone with aphasia, engaging in this practice may feel different. While the guided words might not always land clearly or fully, the person can still sense and respond to what’s being felt in their body. The experience may be less verbal and more somatic or intuitive.

Rather than visualising thoughts or narrating sensations, someone with aphasia might:

- Tune into body signals like warmth, breath, or tension

- Experience rhythms in the guide's voice as soothing, even if not fully understood

- Respond more to tone, pauses, or repetition than to specific instructions

- Feel a general sense of safety or agitation based on how the practice is delivered

In this way, the Wheel of Awareness still holds value. It offers a structure for noticing and integrating experience — even if the 'spokes' of attention are accessed through sensation rather than words. For those living with aphasia, the practice may open space for calm presence, even when language is quiet or unclear.

What the Research Says

Research shows that aphasia is a language disorder caused by brain injury, most commonly from stroke, that affects speaking, understanding, reading, and writing—but not intelligence (Code & Herrmann, 2003). People with aphasia often retain full emotional and cognitive capacity, even when their ability to express themselves is disrupted.

In trauma-related cases, similar disruptions in language can occur. Studies show that childhood trauma can impair interoceptive awareness—the ability to sense internal bodily states—leading to body dissociation and emotional dysregulation (Barrett & Simmons, 2023). These disruptions are often linked to the insula, a brain region that helps integrate internal sensing with emotional and verbal processing (Craig, 2009).

The insula is also involved in coordinating speech. Damage to this region, whether from trauma or stroke, can result in speech production difficulties and a breakdown in awareness of bodily signals (Dronkers, 1996). This explains why some individuals with aphasia or trauma may struggle to connect language, emotion, and bodily experience, even when cognitively intact.

Mindfulness-based practices like Dr. Dan Siegel’s Wheel of Awareness may offer therapeutic benefits by gently restoring interoceptive awareness and supporting emotional regulation—even for those with language difficulties. Practices that emphasise tone, rhythm, and bodily sensation may be especially helpful.

References

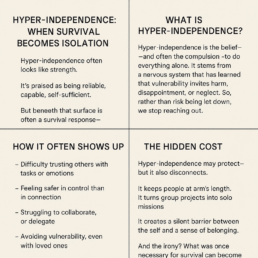

When Strength Is a Shield

Hyper-independence is often mistaken for strength. It’s praised in society as self-reliance, competence, and resilience.

But underneath the polished surface lies a very different story — one of pain, protection, and deep survival.

What Is Hyper-Independence?

Hyper-independence is the compulsion to carry everything alone.

It’s the belief that asking for help is dangerous. That trusting others is a risk not worth taking.

It’s not a personality quirk — it’s a nervous system response formed in the fire of unmet needs, broken trust, and chronic invalidation.

While it can stem from childhood trauma — like emotional neglect, inconsistent care, or having to grow up too soon — it is just as often shaped by what happens when people reach out for support and are betrayed.

When Support Fails, Survival Steps In

Many who carry hyper-independence have tried to seek help before.

But instead of care, they were met with:

- Suspicion instead of safety

- Judgement instead of compassion

- Pathologising labels instead of understanding

- Questions that implied they were to blame

- Systems that protected the abuser and silenced the victim

This kind of betrayal cuts deep. It teaches the body and mind that asking for support only leads to further harm.

And so, the nervous system adapts.

It says:

- Don’t explain yourself — they don’t want to understand.

- Don’t ask for help — it won’t come.

- Don’t trust anyone — they’ll turn it against you.

And from that place, hyper-independence is born.

What It Looks Like in Daily Life..

- Struggling to collaborate or delegate

- Avoiding group projects due to misaligned energy

- Taking control to feel safe

- Reading people’s energy before they even speak

- Withdrawing at the first sign of judgement

- Feeling responsible for everything — and everyone

This behaviour isn’t arrogance. It’s protection.

It’s a response to a world that has, at times, punished vulnerability rather than honoured it.

There is a Hidden Cost

Hyper-independence isolates.

It creates a silent barrier between the self and true connection.

It turns working with others into working around them.

And most tragically — it cuts people off from the very thing that heals: relational safety.

Because underneath the control and competence is often someone carrying a deep belief:

“I am the only person I can trust.”

Healing Is Possible — But It Requires More Than Therapy

Healing hyper-independence isn’t about swinging to dependency — it’s about rediscovering interdependence.

It begins with creating spaces that feel safe enough to let the guard down.

Where people are believed.

Where stories aren’t twisted into diagnoses.

Where presence replaces judgement.

Where relationships are rooted in trust, truth, and mutuality.

It begins with choice.

Not forced compliance.

Not control masked as care.

But genuine, informed, trauma-aware choice.

My Final Thoughts…

If you recognise yourself here, know this:

Your hyper-independence was never weakness.

It was wisdom.

Your body, your mind, your instincts — they protected you.

And now, as safety slowly returns, you can begin to choose something different.

Not because you’re broken.

But because you are finally safe enough to stop carrying everything alone.

www.apositivestart.org.uk

When Complex Trauma Shapes Our Thinking

It starts as something simple.

A message.

A warm, friendly “Hey, want to grab a coffee?”

But what happens next says far more about trauma than it does about coffee.

The message is read — but not replied to.

The person who sent it begins to feel a ripple of discomfort.

They check their phone again.

Still nothing.

They’ve seen it… Why haven’t they answered?

They must be avoiding me.

Did I do something wrong?

I’ve upset them… again.

They hate me.

Meanwhile, the friend who received the message?

They’re just busy. Cooking, driving, working, or distracted by life.

They smiled at the message — and fully intend to respond when they have a moment.

But the sender doesn’t know that.

Their mind spirals. Their chest tightens. They pace. Ruminate. Replay conversations in their head, trying to spot the moment they messed it all up.

They’re thrown out to sea with no raft — treading water, emotionally overwhelmed, heart pounding with a quiet terror they can’t fully explain.

Eventually, they type a second message:

“I’m sorry if I’ve upset you — I understand.”

Now the friend is confused and on edge.

What are you talking about? I’m just busy. Why would you think that?

Both people are now dysregulated.

Both are reacting from past experiences.

And neither intended to hurt the other.

What’s Really Going On?

The unseen weight of complex trauma and core beliefs!

When someone grows up in an environment where love was conditional, inconsistent, or unsafe, their nervous system wires itself for survival.

They become hyper-attuned to changes in tone, energy, or availability — because in childhood, those changes often signalled danger or abandonment.

This kind of complex trauma shapes deep core beliefs, like:

- I am too much

- I don’t matter

- People always leave

- If I make a mistake, I’ll be rejected

- I have to earn my place in someone’s life

So, when something as simple as a pause or silence happens, it isn’t experienced neutrally —

it activates the entire history of being dismissed, abandoned, or emotionally unsafe.

The body reacts. The mind scrambles for answers.

But the moment isn’t about the coffee anymore — it’s about reliving the past through the lens of the present.

Now there are two realities

- The sender is in emotional panic, experiencing abandonment.

- The receiver is confused, experiencing pressure or guilt.

What started as a simple exchange now feels like conflict or rejection — for both.

We often hear about the importance of self-regulation — but for those with complex trauma, the ability to self-soothe wasn’t developed in early life.

Why?

Because we learn to self-regulate by being co-regulated first.

As children, we need consistent, attuned caregivers to hold us through distress. To say, “You’re OK. I’m here.” To model calm. To help us find our way back to safety.

Without that, we’re left alone with big feelings — often punished or ignored for having them.

So when distress arises in adulthood, we may not have the internal tools — the raft — to stay afloat.

We reach out. We apologise too quickly. We panic.

Not because we’re broken, but because we’re doing what we always had to do to survive.

Self-regulation comes after co-regulation.

It’s learned through safe, attuned relationships — and repeated practice.

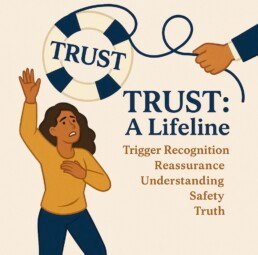

🛟 This is where the

TRUST framework comes in

Healing doesn’t mean never getting triggered.

It means noticing what’s happening, and responding in a new way.

TRUST:

Trigger recognition

Reassurance

Understanding

Safety

Truth

How TRUST helps in this moment:

- T – Trigger Recognition

The sender pauses: “This feels intense — is it about now, or am I being reminded of something old?” - R – Reassurance

Instead of spiralling, they ground: “My friend probably hasn’t had time. I am still safe. I can wait.” - U – Understanding

Compassion flows both ways. The sender understands their own wounds. The friend sees the deeper context. - S – Safety

A moment of self-regulation changes the direction. Maybe no second message is sent, or it’s worded differently:

“No worries if you’re busy — just checking in when you’ve got time.” - T – Truth

The imagined story (they’re mad at me) is replaced with reality (they were just busy).

It only takes one person to throw the lifeline!

Whether it’s you or the other — someone’s nervous system has to stay grounded to calm the storm.

But ideally, both people begin to notice the pattern, own their stories, and support safer connection.

This is the work we do through trauma-informed support.

This is why TRUST matters.

TRUST Training by A Positive Start - with Lived Experience Insight…

Because positive outcomes begin with…

A Positive Start.

#TRUST

#TriggerRecognition

#CoreBeliefs

#ComplexTrauma

#RelationalHealing

#TraumaInformedSupport

#SelfAwareness

#EmotionalRegulation

#APositiveStartCIC

#HealthyCommunication

#InnerSafety

#RelationalSafety

A trauma-informed approach to everyday challenges

Parenting is one of the most important — and most complex — roles we’ll ever take on. It doesn’t come with a manual, and many of us are learning in real time, often while healing from our own past experiences.

If you’ve ever found yourself saying things you didn’t mean or reacting in ways that didn’t feel aligned with your values, you are not alone. Many of us are simply repeating what we heard or experienced as children, without even realising it.

The good news is this: change is possible — and it starts with awareness, not perfection.

This guide isn’t about blame or getting it “right” all the time. It’s about offering new language that helps children feel safe, seen, and supported, especially in moments of challenge. It’s okay if this feels unfamiliar at first. Like any new skill, it takes time, patience, and lots of self-compassion.

You’re not expected to be perfect — just present. Every small shift you make towards connection matters. Every moment of repair, curiosity, or calm presence helps shape your child’s nervous system, and your own.

Let’s explore this together, one gentle step at a time.

This guide offers compassionate, trauma-informed language to support children who are pushing boundaries, expressing needs through behaviour, or struggling with routine tasks. These phrases help create connection, safety, and understanding.

1. When a child isn’t listening to 'no'

Instead of: “How many times do I have to tell you? I said NO!”

Try:

“It looks like that ‘no’ felt hard to hear. Do you want to tell me what you were hoping for?”

2. When a child doesn’t want to wash hands/face

Instead of: “Stop being difficult — go wash your hands now!”

Try:

3. When they resist brushing their teeth properly

Instead of: “Brush them properly or you’ll get bad teeth!”

Try:

4. When rules are ignored or broken

Instead of: “You’re not listening again! Why can’t you just follow the rules?”

Try:

5. When a child resists bedtime

Instead of: “Enough! Go to bed now or no stories!”

Try:

We are all learning — children and grown-ups alike.

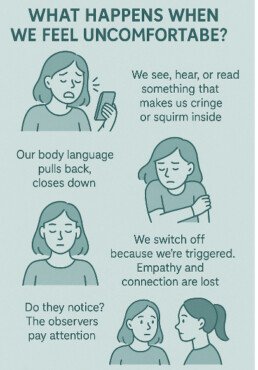

What Happens When We Feel Uncomfortable?

What Happens When We Feel Uncomfortable?

- And Why That Discomfort Might Be a Clue, Not a Problem

Ever felt yourself physically or emotionally pull back when something doesn’t sit right?

You hear a story…

You read a post…

Someone shares something real, raw, painful—

And inside, you squirm.

You tense.

You cross your arms.

You scroll faster.

You check out.

You’re not cold. You’re not uncaring.

Your nervous system is protecting you.

It’s subtle. Often unconscious. But powerful.

You may not notice.

But your body does.

Others notice - those sensitive to change, hyper-vigilant, Neurodivergent, traumatised, the present & mindful #Neuroception

Your body recognises something before your mind does.

It senses discomfort, and the threat response kicks in.

You disconnect.

You stop feeling.

You shut down.

This is dysregulation.

And it’s more common than most people realise.

When we’re dysregulated, we’re not present.

We’re not connected to ourselves—or others.

We can’t co-regulate.

We can’t empathise.

We’re in survival mode.

A dysregulated adult cannot regulate a dysregulated child or another adult.

This matters deeply for parents, carers, teachers, therapists and helping professionals.

Because when your nervous system is shut down, you’re not available, even if your body is in the room.

The first thing I teach my counselling students is this:

You cannot support someone else’s healing if you are not present in your own body.

And that’s no one’s fault.

But we must notice it.

Because overwhelmed staff, however well-intentioned, aren’t just tired—

They’re dysregulated.

And a dysregulated workforce cannot offer consistent safety to those they serve.

So what can help?

One answer lies in understanding what might be trapped inside us.

According to Dr. Bradley Nelson, author of The Emotion Code, many of us carry trapped emotions—energetic imprints from unresolved past experiences, often from childhood.

These emotional imprints shape how we think, feel, and act.

That’s why in our STAND – Parents as Protectors program, we explore the Think–Feel–Act process:

What was the thought?

What did I feel in my body?

What did I do in response?

By slowing things down, we can begin to notice our patterns.

By noticing our patterns, we open the door to healing.

And when we heal, we reconnect.

Because the goal isn’t perfection—

It’s presence.

So today, just notice:

What makes you pull back?

Where does your body react before your mind catches up?

What would it take to stay present—even for a moment longer?

Awareness is the first step.

Compassion is the second.

Healing happens in connection.

Let’s go deeper.

What happens after we disconnect?

When Judgement Is a Nervous System Response - And Why It Might Say More About Safety Than Truth!

Often—we judge.

We criticise.

We label.

We might even diagnose or pathologise—especially in professional settings.

But have you ever asked yourself:

❓ What’s happening in me when I move into judgement of someone else?

❓ Why do I feel the urge to define them, fix them, or dismiss them?

More often than not, judgement is a symptom of a dysregulated nervous system.

When we feel unsafe—but don’t recognise it—our mind steps in to make sense of the discomfort.

And that sense-making often sounds like:

“They’re too much.”

“They’re unstable.”

“They must have a disorder.”

“They need to calm down.”

Judgement gives us the illusion of control when we’ve lost connection.

It’s a defence—because empathy feels too vulnerable when our own system is overwhelmed.

In trauma-informed practice, we pause and ask:

Is this a reaction to the other person? Or a reaction to my own dysregulation?

Because pathologising another human being can be a bypass.

A way to avoid feeling what’s been stirred in us.

And while diagnostic frameworks have their place,

When we use them to distance, diminish, or dismiss— We’re no longer supporting.

We’re protecting ourselves from what we haven’t yet made sense of.

This is why in our STAND – Parents as Protectors program, we challenge the habit of labelling others before we’ve explored our own regulation.

We ask:

“What’s really going on in me right now?”

“Am I thinking clearly?”

“Can I feel my body?”

“Am I reacting from my past or responding to the present?”

Because when we’re regulated, we don’t need to shame, blame or name-call.

We can hold space.

We can stay curious.

We can see the human, not the label.

So today, if you find yourself judging someone harshly—

Pause.

Breathe.

Notice your body.

And ask:

Is this judgement… or is this protection?

Do I feel safe enough to see them clearly, without turning them into a threat?

True trauma-informed care doesn’t start with diagnosing others.

It starts with regulating ourselves.

We’ve explored what happens when we disconnect…

When we move into judgement of others…

But what about when we turn it inward?

When the voice in our head says:

“It’s all my fault.”

“I’m too much.”

“I should be over this by now.”

“I ruin everything.”

“There’s something wrong with me.”

This too… is often dysregulation.

When our nervous system shifts into survival, we lose access to curiosity, compassion, and clear thinking.

We don’t see ourselves accurately.

We see ourselves as the problem.

This internal collapse is rooted in past experiences where connection was withdrawn, emotions weren’t safe to express, or where our needs were too big for the people around us to meet.

So we adapted.

We blamed ourselves.

We made ourselves small.

And that pattern became automatic.

In trauma work, we call this internalised shame.

It’s not a character flaw.

It’s a protective strategy your body learned to survive disconnection.

When we feel dysregulated, shame often rushes in.

It fills the space where safety, co-regulation, or understanding should have been.

And here’s the paradox:

The more we judge ourselves…

The more dysregulated we become.

The more dysregulated we are…

The more likely we are to judge.

That’s why self-compassion isn’t fluffy or indulgent—

It’s vital for healing.

It’s the pathway back to safety.

In our STAND – Parents as Protectors program, we support participants to recognise this pattern using the same Think–Feel–Act process:

What’s the thought?

What’s the feeling in my body?

What’s the automatic response?

By becoming aware of this cycle, we create space to choose differently.

We learn to pause, breathe, and remind ourselves:

“This is old.”

“This is survival, not truth.”

“I don’t need to shrink to be safe anymore.”

The voice of shame is not your truth.

It’s your nervous system trying to protect you—

By turning you against yourself.

So today, if your inner critic is loud,

Pause.

Place a hand on your heart.

And ask:

What does my body need to feel safe right now?

What would kindness say?

Because healing doesn’t happen through shame.

It happens through safety, slowness, and self-connection.

You don’t have to be hard on yourself to grow.

You just have to come home to yourself—one breath at a time.

#TraumaInformed

#NervousSystemAwareness