When Collaboration Isn’t Collaboration: On Alignment, Authenticity, and the Quiet Politics of Community Work

I’ve been reflecting on a question I was asked recently during a community ‘collaboration hub’ session:

“What stops you from collaborating with others?”

Around the table, the responses were mostly:

- Time

- Funding

- Capacity

- Opportunity

I listened. Considered. I understood what they meant — but none of these have ever really stopped me.

Time?

I am always busy. Truly. My schedule is full most days from early morning to late evening — and yet I still collaborate when the work aligns with my values.

Funding?

I am often broke. I collaborate for free regularly. I share ideas, resources, time, energy and heart because not everything meaningful is transactional.

Opportunity?

There is always opportunity. There is always something we could do together, some bridge we could build, some gap we could close — if the intention is mutual and the work is real.

So I answered:

“Alignment.”

Because I don’t struggle to collaborate.

I show up.

I contribute.

I build, share, create and grow with others — joyfully — when the collaboration is real.

What I struggle with is when what is called collaboration is actually something else entirely.

When You Turn Up and It’s Already Decided

So often you’re invited into a “shared project,” but when you arrive, everything has already been arranged:

- The roles are already set

- The decisions already made

- The leadership already assumed

- And your involvement framed around what you can do for them

Not what we can create together.

In those moments, it becomes clear:

You weren’t invited as an equal partner —

you were invited for free labour, visibility, or credibility.

And when you name that imbalance gently and honestly, the narrative flips:

Suddenly you are:

- Ambushing

- Taking over

- Making it about yourself

- Being “difficult”

When in reality, the opposite is true.

They did not want collaboration.

They wanted your work without your voice.

The Performance of Community

There is a public language of collaboration:

- “We should all work together…”

- “We’re stronger in partnership…”

- “Community is everything…”

And then there is the lived practice:

- Showing up for each other

- Responding to emails

- Sharing events

- Supporting without needing recognition

- Celebrating someone else’s success without comparison

It is easy to speak of community.

Much harder to practice it.

Too often, collaboration becomes:

- Meetings without movement

- Promises without presence

- Community language without community action

I have no interest in performing community.

I am here to build it.

When Truth Confronts Convenience

As manager in another community project, I was once asked why we didn’t recycle e-bikes.

But the conversation wasn’t really about sustainability — it was about finding a convenient way to dispose of unwanted e-bike batteries.

The “collaboration” being suggested would have meant:

- We take on the labour

- We take on the cost

- We take on the risk

- They receive the benefit of looking environmentally responsible

So I asked one question:

“Can you assure me that the batteries were ethically mined — and that no child labour was involved?”

The room fell silent.

Not reflective silence.

Not thoughtful silence.

Not curious silence.

Not, ‘that’s an important question that we need to find the answer to’ type silence

Avoidant silence.

Avoidant, uncomfortable silence.

No one explored the ethical issue.

No one acknowledged the impact.

No one answered.

Instead, I was quietly repositioned as:

- Difficult

- Confrontational

- “Awkward”

But I wasn’t being awkward.

I was safeguarding.

I was ensuring integrity.

I was asking that we do what we say we care about.

They wanted the benefits of collaboration without the responsibility of it.

They wanted our work, our time, our ethics, our labour — while they kept the credit and the public image of being eco-conscious.

This is what I mean when I talk about alignment.

Collaboration is not:

- “You do the work.”

- “I get the recognition.”

- “We call it community.”

Collaboration is shared power, shared responsibility, shared purpose.

When that is missing — it is not collaboration.

Collaboration requires our actions match our values.

Yet in many community spaces, the appearance of doing good is valued more than the integrity of doing good.

What Real Collaboration Feels Like

I know for certain true collaboration exists — because I’ve experienced it.

The River Room Songbook with Chrissy Sykes is:

- Heart-led

- Equal

- Safe

- Mutual

- Larger than either of us

There is:

- No ego

- No power struggle

- No performance

- No silent competition

Just two people doing what matters, because it matters.

It is easy, because it is true.

That kind of collaboration is rare.

Not because it should be rare —

but because it requires:

- Shared power

- Transparency

- Emotional maturity

- And the ability to celebrate someone else’s gifts

Many talk about collaboration.

Few actually know how to do it.

So What Actually Stops Me Collaborating?

Not time.

Not funding.

Not opportunity.

Misalignment.

I will not collaborate where:

- Power is predetermined

- Support only flows one way

- Honesty is unwelcome

- Ego is driving the work

- Or truth is treated as a threat

But I will collaborate — deeply and joyfully — where:

- Integrity leads

- Voices are equal

- Credit is shared

- Accountability is real

- And the work matters more than the spotlight

Because I am not interested in performing community.

I am here to build it.

Perhaps this is the real question in all of it:

Why is speaking truthfully about what you really feel so badly received?

Why does honesty — spoken calmly and without malice — cause such disruption?

Because truth asks something of people.

It asks them to look at themselves.

To examine motive.

To reflect on whether words and actions align.

And for many, that is deeply uncomfortable.

So I’ll say this plainly:

Don’t ask the question if you do not want the honest answer.

This is not about judgement — it is about clarity. Clarity allows collaboration to be real.

Some people will welcome that.

Some will not.

Either way: I’ll never dilute myself to fit into rooms where truth is treated as an inconvenience.

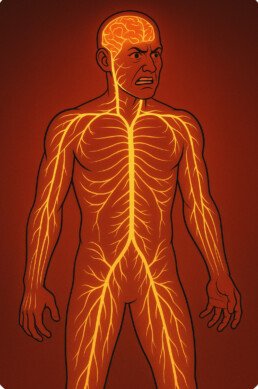

Trauma-Informed Healing Through Nervous System Awareness

Using embodied nervous system attunement to help people recognise, regulate, and return to themselves with dignity and care.

My understanding of nervous system states began very early in my life. After a near-death experience as a young child, my body seemed to pay close attention to the world around me.

I spent part of my childhood in Africa — curious, adventurous, and endlessly observant. I was the child who wandered off to explore, to understand, to feel the world directly. I was captivated by people, landscapes, sounds, and atmosphere. Even then, I sensed things through my body first.

Like many families, we went through a lot. From an early age, I learned to notice emotional shifts before they were spoken. I didn’t have the language for it then — I simply knew.

That sensitivity stayed with me. Over the years, it became something deeply woven into the way I relate to others.

Later in life, I experienced another near-death event due to domestic violence, when my life was threatened and I lost consciousness.

When I survived, my nervous system eventually returned with a clearer sense of what safety felt like — and what it didn’t. The sensitivity I had carried since childhood became more finely attuned and grounded.

From Survival to Understanding

As life unfolded, there were times when safety wasn’t certain — times when my nervous system had to stay alert to protect me.

In those moments, the part of me that could sense subtle changes became finely tuned.

I learned:

- when someone was beginning to shut down,

- when overwhelm was building beneath the surface,

- when words didn’t match the energy in the room.

But as I healed, studied, and grew, something important happened:

What was once hypervigilance slowly transformed into attunement.

No urgency.

No fear.

Just clear, grounded awareness.

Before trauma-informed practice became a recognised framework or widely used term, many of us were already learning to understand trauma from the inside out. Not through theory, but through lived experience, reflection, and the slow work of making sense of ourselves.

My learning happened long before the language became mainstream — in noticing what calmed the body, what overwhelmed it, what restored safety, and what dissolved it. Over time, this became a way of being with others: listening not only to words, but to breath, pace, posture and presence. In that sense, becoming trauma-informed was not something I “learned” later — it was something that unfolded through my own healing.

I don’t imagine I have all the answers, nor do I believe there is one path that fits everyone. Healing is deeply personal. It has taken many years of learning, unlearning, reflection, therapy, regulation, and courage to arrive at a place where I can trust myself and discern what I sense. My confidence does not come from certainty — it comes from knowing myself, understanding my own nervous system, and being able to meet others from a place of steadiness rather than assumption.

Sensing Nervous System States

When I sit with someone, I can often feel:

- the quiet drop into dorsal vagal collapse — when someone begins to numb or disappear inward.

- the rising activation of sympathetic stress — the tightening, the bracing to cope or perform.

- the warmth and presence of ventral safety — when someone is connected, at ease, and available.

I sense these things through:

- breath

- silence

- posture

- the emotional “temperature” of the space between us

Not as alarm anymore.

But as information that guides gentle, respectful support.

Recognising Coercion and Manipulation in the Body

Coercion rarely begins with words.

It begins with subtle shifts in power and pressure.

I feel those shifts before they become visible.

Not because I am suspicious — but because my nervous system has lived through those patterns and learned to recognise them quietly and clearly.

The difference now is that I trust my body’s signals.

Not as fear — but as discernment.

This is not something that can be taught in a classroom.

It is lived, integrated, and softened through healing.

A Unique Offering

Many professionals learn about trauma through theory.

I learned about it first through lived experience — and then spent years transforming that knowing into grounded, compassionate, trauma-informed practice (long before the language of “trauma-informed care” became widely known).

Today, this embodied sensitivity is the foundation of my work.

My work isn’t about trauma stories. It is about helping people return to themselves — gently, respectfully, and with dignity.

Because I know what it is to lose connection.

And I know what it is to find it again.

I now offer trauma-informed consultancy, workshops, and therapeutic support for individuals, families, and organisations who want to create environments where people feel safe, understood, and able to reconnect with themselves.

My work is grounded not only in professional training, but in a finely tuned, embodied awareness of the nervous system. I am able to sense dysregulation before it becomes overwhelm, recognise shutdown before it turns to withdrawal, and support people to return to safety gently and with dignity.

If your organisation, team, or community is ready to move beyond theory and into felt safety, relational presence, and nervous system-informed practice, I’d be honoured to collaborate.

This is work that changes lives — from the inside out.

The Bridge Between Chakras, the Vagus Nerve, and Interpersonal Neurobiology

Have you ever sensed that science and spirituality might be describing the same truth in different languages?

I’ve often reflected on how the vagus nerve, the chakra system, and Interpersonal Neurobiology (IPNB) all seem to meet at the same intersection — where energy, emotion, and connection flow together.

A Meeting Point Between Science and Spirituality

While the connection between chakras and the vagus nerve isn’t formally recognised within mainstream neuroscience, an increasing number of integrative and trauma-informed practitioners are exploring these parallels.

The two systems appear to describe the same process through different languages — one energetic, the other physiological. Ancient traditions spoke of energy flow and alignment, while modern science now studies vagal tone, regulation, and neuroception.

Both ultimately point to the same truth: when the body feels safe and connected, energy and awareness flow freely.

Root to Crown: The Gut–Brain Pathway

The root chakra represents grounding, safety, and belonging — the foundation of our being. The third eye chakra represents clarity, intuition, and insight — our ability to perceive truth and meaning.

In scientific language, the vagus nerve physically connects these realms. It runs from the brainstem through the face, heart, and gut, creating a direct gut–brain communication line.

When the vagus nerve is balanced, we feel safe, grounded, and connected — our body and intuition communicate freely. When it’s dysregulated, we feel unsafe, disconnected, or numb.

In this way, the vagus nerve can be seen as the biological bridge between the root and the third eye — translating instinct into insight, and safety into presence.

Blocked Energy or Trapped Trauma?

Ancient wisdom tells us that energy becomes “blocked” when emotion or life force cannot move freely through the chakras.

Modern trauma science says something strikingly similar: when survival energy (fight, flight, freeze, or fawn) isn’t released, it becomes trapped in the nervous system.

Both perspectives describe a disruption of flow — whether we call it prana or vagal tone. Healing in both systems involves restoring movement, breath, sound, and connection so the energy of life can circulate again.

How the Chakras Relate to the Vagus Nerve

The vagus nerve and chakra system seem to describe the same energy flow through two different lenses: one biological, one energetic.

| Chakra | Location | Theme | Related Vagus Function |

| Root (Muladhara) | Base of spine | Safety, stability, survival | Regulates digestion and elimination; grounding the body in a sense of safety. |

| Sacral (Svadhisthana) | Below the navel | Emotion, creativity, relationships | Influences reproductive and gut organs; supports emotional flow and connection. |

| Solar Plexus (Manipura) | Upper abdomen | Confidence, personal power | Controls diaphragm and gut; where we sense our inner strength and gut feeling. |

| Heart (Anahata) | Centre of chest | Love, compassion, connection | Directly affects heart rate and breathing rhythm; the centre of relational safety. |

| Throat (Vishuddha) | Throat | Communication, truth, expression | Upper branch controls voice tone, swallowing, and facial expression — the social engagement system in Polyvagal Theory. |

| Third Eye (Ajna) | Forehead | Intuition, perception, insight | When vagal tone is balanced, brain and body communicate freely, enhancing intuition. |

| Crown (Sahasrara) | Top of head | Spiritual connection, unity | Reflects integration and coherence; the sense of being connected to something greater. |

Each chakra aligns with areas influenced by the vagus nerve, creating a shared pathway for safety, regulation, and awareness.

When the vagus nerve functions well, energy naturally rises through the chakras, supporting safety, connection, and consciousness.

When it’s disrupted, the flow of energy — or prana — becomes constricted, and we experience symptoms of imbalance, anxiety, or shutdown.

Trauma and the Flow Between Root and Third Eye

Dr. Wayne Dyer once suggested that trauma disrupts the energetic flow between the root chakra and the third eye, and this insight aligns closely with both ancient and modern understanding.

The root chakra represents our sense of safety and belonging — our foundation.

The third eye represents awareness, clarity, and intuition — our ability to perceive beyond the surface.

When trauma occurs, especially in early life, it destabilises the root, leaving the body in a constant search for safety.

In this state, energy can’t rise freely toward the higher centres, particularly the third eye, where intuitive and spiritual awareness reside. The result is a kind of inner fragmentation — the body and mind no longer move together in harmony.

From a scientific perspective, the vagus nerve mirrors this same disruption. Trauma interrupts the communication between the gut (root) and the brain (third eye) — the very flow that allows instinct and intuition to cooperate. The lower vagal circuits enter survival mode, and the upper pathways that support calm awareness and insight go offline.

This explains why, after trauma, many people feel either hypervigilant and disconnected from their intuition, or numb and dissociated from their body. They can’t “feel” their truth because safety and perception have become disconnected.

Healing, therefore, involves restoring the flow between the root and the third eye — through grounding, breath, sound, movement, and safe relational connection. As safety returns to the body, awareness naturally expands.

The Ahhh sound meditation that Dr. Dyer often taught vibrates through the throat, heart, and head, gently bridging these energetic and neural circuits, helping the nervous system re-establish coherence between body and spirit.

When the root feels safe, the third eye opens — and insight is grounded in embodied awareness.

Interpersonal Neurobiology: The Relational Bridge

Interpersonal Neurobiology (IPNB), a framework developed by Dr. Dan Siegel, shows that integration — linking separate parts into a functional whole — is the foundation of well-being.

It views the mind as an embodied and relational process that regulates energy and information flow.

That’s exactly what both the chakra system and Polyvagal Theory describe:

- The vagus nerve regulates our internal state and sense of safety.

- The chakras reflect the energetic expression of that state.

- IPNB shows how safe, attuned relationships support this integration, restoring harmony across body, mind, and spirit.

Where trauma fragments, integration unites.

Through connection, compassion, and self-awareness, energy begins to flow again — physiologically, emotionally, and spiritually.

In Essence

Science and spirituality are not opposites; they are two mirrors reflecting the same truth:

- When the nervous system feels safe, energy flows.

- When energy flows, intuition awakens.

- When presence meets connection, healing happens.

The vagus nerve, the chakra system, and IPNB each describe what it means to be human — wired for safety, connection, and flow.

When the Body Knows Before the Mind

Understanding fainting, fear, and the wisdom of the vagus nerve

Someone once told me they believe they faint in the presence of evil.

To some, that might sound far-fetched or even dramatic — but to me, it made perfect sense.

I believe there’s truth in it, though perhaps not in the way it first appears.

When the body detects overwhelming threat, the vagus nerve — the great communicator between brain and body — can trigger an emergency response. It slows the heart, drops the blood pressure, and reduces blood flow to the brain. Consciousness fades, and we faint.

This is called vasovagal syncope, and it’s the body’s most extreme form of self-protection — a complete “cut-out” when survival energy becomes too much to process.

A nervous system that learned fear early

As a young person, I fainted often — sometimes weekly. Especially in church or at school.

It took years before I understood why.

When I was seven, a teacher humiliated me in front of my classmates. At nine, a nun stabbed my hand with a pen and shamed me publicly. Those moments left deep marks — not only in memory but in my nervous system. My body learned that authority, church, and classrooms were dangerous places.

So even when nothing “bad” was happening years later, just stepping into those environments triggered the same fear pathways. My nervous system didn’t distinguish between past danger and present safety. The fainting was my body’s way of saying, “I can’t bear this. I’m shutting down.”

The body’s secret surveillance system

Stephen Porges calls this neuroception — the body’s unconscious ability to detect safety, danger, or life threat.

Unlike perception (which is conscious), neuroception happens automatically, below awareness. It’s an ancient survival mechanism that continuously scans the world around us and inside us, asking:

“Am I safe, or am I in danger?”

It listens to tone of voice, facial expression, posture, energy, and even the spaces between words. It detects micro-signals — the subtle shifts in presence and intention that our thinking brain may never notice.

This means we can feel danger long before we understand it.

We might walk into a room and suddenly feel uneasy. Our stomach tightens, our breathing changes, or our heart races — and we don’t know why. That’s neuroception at work.

When someone says they faint in the presence of evil, perhaps what they’re really describing is this:

Their body perceives a profound energetic or moral threat — something cold, unsafe, or deeply incongruent — and the vagus nerve steps in to protect them from overwhelm.

When words fail, the body speaks

Looking back, I see those fainting episodes not as weakness, but as wisdom.

They were my body’s attempt to manage what I couldn’t process.

What religion called “sin” and psychology might call “trauma,” the nervous system simply calls too much.

The body doesn’t lie. It tells its truth in sensations, symptoms, and sometimes in silence.

And when the cues of safety return — through compassion, connection, and time — the same body that once shut down can begin to reopen, soften, and trust again.

So yes — I do believe there’s truth in the idea of fainting in the presence of evil.

But I see it through a different lens now.

Not superstition. Not weakness.

Just the ancient intelligence of the body — doing its best to keep us alive in a world that sometimes felt unsafe to feel.

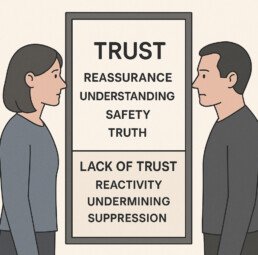

The Opposite of TRUST: A Mirror We All Must Face

Trauma-informed practice isn’t just about understanding others — it’s about choosing how we show up in every interaction.

Every day, in every conversation, we have a choice:

To walk the path of alignment, compassion, and light — or to fall into the unconscious patterns that perpetuate harm.

Even those who intend to help can become part of the problem when awareness slips. And that’s why I’ve been reflecting deeply on TRUST — the framework that underpins my trauma-informed work — and its shadow opposite.

Because everything that heals can also be inverted to harm.

The TRUST Framework

(A Trauma-Informed Approach)

T – Trigger Recognition

Awareness of what activates fear, pain, or defensiveness — in ourselves and others — so we can regulate before we respond.

R – Reassurance

Offering calm, consistent presence that tells the nervous system: “You’re safe now.” Reassurance rebuilds trust where fear once lived.

U – Understanding

Seeking to understand the why behind behaviour, not just the what. It’s choosing empathy over judgment and compassion over control.

S – Safety

Creating physical, emotional, and relational environments where people feel seen, heard, and safe enough to heal.

T – Truth

Honesty with self and others. Congruence. Saying what we mean and meaning what we say — because truth and safety cannot exist without each other.

This is the path of awareness, compassion, and connection — the path of light and alignment. It’s how we heal, lead, and create genuine change.

The Shadow of TRUST

(A Trauma-Perpetuating Approach)

T – Trigger Recognition

Still present — but used manipulatively. Recognising what provokes others, not to heal but to control.

R – Reactivity

Acting from fear or ego. Escalating rather than calming. Reacting to protect self-image instead of building safety.

U – Undermining

Eroding another’s confidence or sense of self to maintain dominance or superiority.

S – Suppression

Silencing truth, emotion, or individuality. Valuing compliance over authenticity.

T – Transactional Thinking

Conditional care: “I’ll support you if you behave the way I want.”

Relationships become about control, not connection.

This is the path of power, fear, and disconnection. It can look confident on the surface, but it’s a fragile strength — built on defence, not integrity.

The Choice

Every one of us stands at this crossroads, especially when we’re tired, triggered, or under pressure.

We can respond from trauma — or from truth.

From fear — or from love.

Being trauma-informed isn’t about perfection; it’s about presence.

It’s about noticing which version of TRUST we’re embodying in any moment — and having the courage to choose again.

When we walk the path of alignment, our energy becomes restorative rather than depleting.

We repair what we once repeated.

We regulate, reconnect, and rebuild — one conscious choice at a time.

Which path are you on in your journey?

Do you ever switch between the two? When does that happen?

What do you see in yourself — and what do you see in the world around you?

Self-awareness is the path to happiness.

When Truth Becomes Too Inconvenient to Hear: Trauma, the Inquiry, and a Hybrid Model for Justice and Repair

The national inquiry has stalled — and for many survivors, the impact runs far deeper than frustration or disappointment. What we’re witnessing isn’t just politics; it’s trauma being reactivated in real time.

When politicians try to control or manage the truth, survivors experience something painfully familiar — being unseen, unheard, ignored, silenced, or not believed. The nervous system doesn’t distinguish between now and then when it senses threat. The body remembers.

Trauma in Real Time

Trauma isn’t the event itself; it’s what happens inside of us as a result of it. It’s stored in the body — in the nervous system. Before healing, anything resembling the original trauma — real or perceived — can trigger an emotional flashback: distressing felt memories that overwhelm the system and activate fight, flight, freeze, or fawn responses.

For me, it was always flight. I could pack a family’s entire life into a Micra in under an hour and start over — new location, new job, new house, new school — inside a week.

To the untrained eye, it looked like chaos — constant movement, instability, unpredictability. But in reality, it was survival.

I wasn’t running from responsibility; I was running from danger my nervous system still believed was real. I don’t call that a disorder; I reserve the word disorder for the violent behaviour that caused it.

We’re seeing those same nervous system dynamics in the inquiry itself:

- Politicians trying to control and restrict (power and dominance)

- Survivors getting angry, frustrated, and fighting back (fight)

- Others walking away, even though it’s the thing they want most (flight)

- And some fawning — aligning with the system to preserve peace and reduce perceived threat (fawn).

Division is the predictable by-product of trauma when safety and trust are missing.

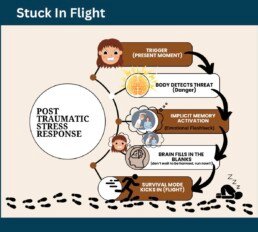

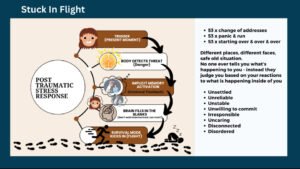

The Cycle of Post-Traumatic Stress

In my Reconnect & Regulate program, I use a diagram called “Stuck in Flight” to help people visualise what happens inside the body when trauma is reactivated:

- Trigger (Present Moment): Something — a tone of voice, a phrase, or a situation — signals danger to the body.

- Body Detects Threat: The nervous system immediately mobilises for survival.

- Implicit Memory Activation: Emotional flashbacks flood in — felt memories, not always visual, that recreate the emotions of the past.

- Brain Fills in the Blanks: Logic shuts down as the survival brain takes over — it assumes danger and prepares to flee.

- Survival Mode (Flight): The urge to escape becomes overwhelming — to run, relocate, start over.

I once experienced this cycle more than fifty times: fifty-three house moves, fifty-three moments of panic, fifty-three new beginnings. Each time, I thought I was running from a situation — but I was really running from a sensation.

People often judged me as unsettled, unreliable, or unwilling to commit, without understanding that what was happening inside of me wasn’t a choice — it was a nervous system doing its best to keep me safe. As a society, we often think with our eyes without looking closer.

From Survival to Healing

Healing is possible. Over time, through deep self-understanding and regulation practices, I learned how to switch off my body’s constant threat response and create safety from within. I developed strategies for processing and recovery — tools I now use and teach every day.

The things that once left me running, hiding, and terrorised are the very things I can now face calmly, without fear. I still notice the traces — echoes of past trauma that occasionally ripple through my nervous system — but instead of reacting, I listen. I pay attention. I respond with awareness and compassion.

That’s what recovery truly is: not erasing the past, but learning to stay present when it whispers.

A Hybrid Model for Justice and Repair

I believe the answer lies in a hybrid inquiry model — one that holds systems to account without causing further harm. A model where truth and healing can exist side by side.

Stage 1 – Judicial-Style Hearings

Independent and transparent hearings where evidence is heard under oath before a balanced panel — including a jury of lived experience. This stage focuses on truth, accountability, and integrity, free from political or media interference.

Stage 2 – Restorative Inquiry

Once the facts are clear, the focus must shift to understanding and repair. Survivors, community members, professionals, and institutions work together to explore how harm occurred and how to prevent it in future. This stage must be guided by trauma-informed principles: safety, compassion, dignity, and choice.

Such a model would allow survivors to be heard without being retraumatised, and systems to be held accountable without being adversarial. It would restore both trust and humanity.

We can’t rebuild public trust by repeating the same patterns.

We need a process that honours truth without causing harm — one where survivors’ voices guide the change that follows.

Maybe it’s time to stop calling these inquiries “investigations” and start calling them what they truly could be — transformations.

The Importance of a Trauma-Informed Approach

For inquiries involving survivors of trauma, the process itself must be trauma-informed — not just in name, but in practice. This means understanding that behaviour is communication, that reactions are shaped by past experiences, and that safety is the foundation for truth-telling.

I use the #TRUST Framework as a simple, human guide for trauma-informed practice:

T – Trigger Recognition: Notice signs of distress or dysregulation and pause before proceeding.

R – Reassurance: Communicate safety and predictability; let people know what to expect.

U – Understanding: Listen to what’s being said beneath the words — attune to emotion and energy.

S – Safety: Prioritise emotional, psychological, and physical safety at every stage.

T – Truth: Honour the truth, even when it’s uncomfortable — truth and safety can coexist.

TRUST allows survivors to stay connected to their voice without their body going into defence. It transforms the inquiry environment from one of reactivity to one of regulation.

The Person-Centred Approach — #CUE

For those chairing or facilitating such proceedings, I believe the person-centred approach offers the most ethical and effective foundation. Carl Rogers identified three core conditions for authentic human connection — what I call the CUE Approach:

C – Congruence: Be real. People feel when something is inauthentic. Authenticity builds safety.

U – Unconditional Positive Regard: Offer respect and value to each person’s experience, without judgement or hierarchy.

E – Empathic Understanding: Seek to understand from within another’s frame of reference — not just what happened, but how it felt.

Applied to inquiries, CUE ensures the tone, body language, and environment all communicate psychological safety. It helps survivors regulate, professionals stay grounded, and truth to emerge naturally — without coercion, suppression, or shame.

Towards True Justice

Justice isn’t only found in courtrooms or inquiry reports. It’s found in the tone that listens, the eyes that see, and the collective courage to repair what was broken.

To the survivors standing up for truth, despite being called liars — please don’t blame yourselves for what’s happening. Your nervous system is responding exactly as it was designed to. You have every right to your voice, your boundaries, and your truth.

Take care of yourself.

The truth will set you free — but it must be held by systems safe enough to hear it.

Deborah J Crozier

Founder at A Positive Start CIC

Advocating for a Trauma Informed Society

From Collapse to Connection: Understanding the Dorsal Vagal State and the Path Back from Despair

When we talk about trauma, we often speak of fight or flight—but rarely of the quietest survival state of all: freeze or collapse.

Yet it’s this state—the dorsal vagal response—that I know most intimately.

After the attempt on my life, when I lost consciousness through strangulation, my body did something remarkable: it protected me the only way it could.

It shut down.

I now understand that moment—and the long, ghost-like months that followed—as dorsal collapse, a state where the nervous system withdraws energy to survive what feels utterly inescapable.

The Three States of the Nervous System

Polyvagal Theory, developed by Dr Stephen Porges, helps us understand how the body organises itself around safety and danger through three main pathways of the autonomic nervous system, each linked to the vagus nerve—the body’s longest cranial nerve connecting brain to body.

- Ventral Vagal — Safety and Connection

When the ventral vagal system is active, we feel open, present, and connected. Our voice softens, our digestion works, and we can think clearly. This is the state where social engagement and healing happen. - Sympathetic — Mobilisation

When we perceive threat, the sympathetic system energises us to fight or flee. Our heart rate increases, adrenaline flows, and we move into survival action. - Dorsal Vagal — Immobilisation and Collapse

When neither fight nor flight can help, the body shifts into the oldest survival strategy—shutdown. Breathing slows, energy drops, awareness fades. It’s the body’s last effort to preserve life by numbing pain and conserving resources.

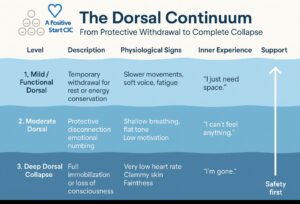

There Are Levels to Dorsal Collapse

Not all shutdown looks the same. Think of dorsal as a continuum—like sinking below the water’s surface. The depth we reach depends on history, context, resilience, co-regulation, and whether the body senses escape or safety.

1 | Mild / Functional Dorsal — Protective Withdrawal

- In real life: going quiet in a meeting, zoning out, needing to lie down after stress, skipping social plans from sheer flatness.

- Common triggers: overstimulation, subtle exclusion, relational disappointment, post-burnout “crash.”

- Body feel: heavy limbs, soft/low voice, shallow breath, “I just can’t right now.”

- Support: warmth, hydration, orienting (notice colours, shapes), light rhythmic movement, permission to rest without shame.

2 | Moderate Dorsal — Numbing and Disconnection

- In real life: emotional blankness after pain (“I know I should be upset but I feel nothing”), losing time, glass-wall feeling.

- Common triggers: chronic invalidation, powerlessness, coercive dynamics, medical procedures.

- Body feel: hypoarousal (cooling, slowed heart rate), dissociation, fog, “Nothing matters.”

- Support: sensation-based grounding (texture, warmth), co-regulation, gentle voice engagement, micro-movement breaks.

3 | Deep Dorsal Collapse — Complete Shutdown

- In real life: freezing mute, curling up, fainting/collapse, out-of-body detachment.

- Common triggers: life-threatening violence, choking/strangulation, witnessing severe trauma.

- Body feel: steep drop in heart rate and blood pressure, clammy skin, irregular breath, possible loss of consciousness.

- Support: safety first—quiet, warmth, steady presence. Mobilise only once the body feels safe enough to rise.

The deeper the collapse, the more energy and safety the body needs to rise again. Healing isn’t forced; it’s coaxed.

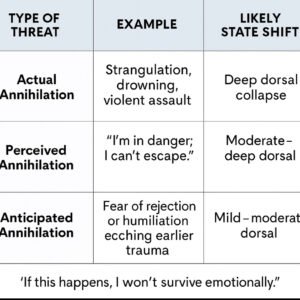

Actual vs Perceived Annihilation

Our nervous systems run on neuroception—a pre-conscious scanning for safety or threat. It doesn’t wait for evidence. That’s why a perceived annihilation (“I can’t breathe”) can evoke the same shutdown sequence as an actual threat to life.

During a panic attack, oxygen is available but the body’s felt sense says “I’m suffocating.”

Hyperventilation lowers carbon dioxide, causing dizziness and tight chest sensations; the brain reads this as life-threatening and may swing from sympathetic overdrive into dorsal shutdown (faint, numb, collapse).

From Dorsal to Sympathetic: Moving Away from the Edge

When someone is in deep dorsal, the first step isn’t positivity or logic—it’s mobilisation.

Tiny increments of movement or breath invite the body back toward agency: standing, orienting, swaying, humming, walking, or sighing. Once energy returns, ventral safety—connection, calm, trust—becomes reachable again.

Recognising “Nearly Crisis”

Even a mild dorsal state can drift into depression and suicidal ideation. Early recognition saves lives.

Watch for:

- Sudden flatness after stress or conflict

- Withdrawal from supportive routines

- Slowed movement, soft monotone voice

- “I feel far away / not really here”

- Cold or clammy skin, shallow breathing

When you see this: lower demands, increase safety.

Soften tone, shorten expectations, offer warmth, grounding, and co-regulation before talking solutions.

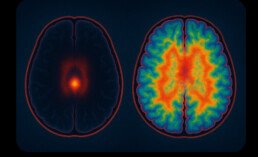

What Recent Neuroscience Is Showing

- Vagal flexibility: Low heart-rate variability (HRV)—less flexible vagal tone—is consistently linked with depression, trauma load, and suicidality risk.

- Brain networks: Chronic threat alters connectivity between the amygdala (fear), insula (body awareness), and prefrontal cortex (control), shaping how quickly we tip into defence and how slowly we return.

- Breath and CO₂: Controlled slow breathing and humming raise CO₂ slightly, calming panic and restoring vagal balance.

- Emerging interventions: Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation, rhythmic movement, music, and vocal exercises show early promise for regulation.

- State before story: Regulation precedes reasoning; once we help the body move between states safely, perspective and problem-solving follow.

What We Don’t Yet Know

- Causality: Research hasn’t yet proven that deliberately shifting dorsal → sympathetic directly reduces suicidal ideation, though clinical experience suggests benefit.

- Measurement limits: HRV is a window, not the whole landscape, of vagal activity.

- Human variation: People blend states—numb yet anxious, still yet tense. History, culture, neurodiversity, and medication alter the picture.

- Anatomy debates: Some Polyvagal details remain contested, yet its framework continues to help us understand lived experience.

- Dosing mobilisation: The “how much, how fast” question still needs empirical study.

Integrating Lived Experience and Research

What I’ve shared brings together lived experience and current neuroscience—reflections formed through both personal recovery and professional practice.

These insights are not medical directives, but an evolving theory-in-practice: an attempt to bridge what the science tells us about the nervous system with what the body teaches through survival and healing.

Polyvagal understanding, when grounded in compassion, becomes relational rather than theoretical—a way of noticing, naming, and nurturing safety in ourselves and others.

Closing Reflection: From Despair to Connection

Understanding the nervous system through a Polyvagal lens helps us spot “nearly crisis” sooner, before despair deepens into collapse. When we recognise the early drift into dorsal, we can respond with gentleness—less demand, more safety, warmth, rhythm, and presence.

Sometimes the bravest thing a body ever did was shut down.

Our work is to honour that wisdom—and gently guide it back to safety.

If You or Someone You Know Is Struggling (UK)

If risk feels immediate, call 999 or go to A&E.

For urgent support: Samaritans 116 123 (free, 24 / 7) or text SHOUT 85258.

You are not alone. There is a way back.

Disclaimer

This article and its visuals reflect my lived experience, professional reflections, and personal interpretation of current trauma and neuroscience research.

They are intended to encourage understanding and dialogue—not to provide medical or scientific advice.

Each person’s nervous system is unique, and anyone experiencing distress or suicidal thoughts should seek appropriate professional and emergency support.

Infographic: The Dorsal Continuum — From Protective Withdrawal to Complete Collapse © A Positive Start CIC created using Ai.

As Above, So Below

I’ve been reflecting, as I regularly do…

Let’s consider the environment.

Chaos on the outside, chaos on the inside.

Calm on the outside, calm on the inside.

Hate on the outside, hate on the inside.

Love on the outside, love on the inside.

This is how it might work for those of us who have experienced the contrast — who know both chaos and calm, hate and love, and can recognise the difference.

But what about those who haven’t?

Those who have only ever known chaos, hate, pain, suffering, and fear?

For them, “as above, so below” isn’t yet a reflection — it’s a distant concept, almost unimaginable.

When the nervous system has only ever known threat, safety feels foreign. When love was absent or unsafe, trust doesn’t come easily. This is the legacy of trauma — particularly complex trauma formed through Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs).

The body learns early that calm can’t be trusted, that quiet might precede danger, and that connection might lead to pain. Fear becomes familiar — and so, when calm appears, the body resists it. It’s not because the person doesn’t want peace, but because peace feels unsafe.

Over time, I began to see how much outside conditioning and programming interferes with our alignment. From childhood messages and cultural expectations to systems that reward productivity over presence, we’re constantly shaped by influences that disconnect us from our truth.

Fear, in particular, disconnects us. It severs the flow between mind, body, and soul — like a hosepipe that’s been kinked or nipped, blocking the water from reaching where it needs to go. In our attempt to survive, we dissociate, shutting down parts of ourselves to avoid suffering. But that same mechanism that once protected us can later become the very thing that prevents healing.

For many years, when I worked directly with clients, I used to take them to the quiet grounds of a local priory. It was a peaceful, sacred place — still, safe, filled with birdsong and open sky. But what I noticed was profound: I could often gauge the depth of trauma by how long someone could simply sit in silence.

For most, it was no more than three minutes before the body began to react — stimming, shaking, rocking, fidgeting, crying, panicking. Their nervous systems could not yet tolerate stillness. Silence felt threatening. Calm triggered chaos.

That experience taught me, again and again, that trauma lives in the body — and it shapes our thoughts from the bottom up, not the other way around. We can’t think our way to safety; we have to feel our way there. Healing begins not with logic, but with the body learning that it is no longer in danger.

For those with complex trauma, this isn’t achieved in a single visit or through a one-off experience of calm. It requires gentle repetition — inviting them back to that calm space over and over again. Each visit creates a new comparison: chaos versus calm, tension versus release, fear versus safety.

Over time, these repeated moments begin to rewire the body’s understanding. What was once foreign starts to become familiar. Eventually, they begin to take the reins and move forward themselves — not because they were told to, but because their nervous system finally feels the difference.

This is where TRUST becomes essential.

T – Trigger recognition

R – Reassurance

U – Understanding

S – Safety

T – Truth

The Trauma-Informed TRUST Framework isn’t a tick-box exercise or a ‘nice thing to have’. It’s purposeful. It’s intentional. And it’s desperately needed. It represents the steady bridge between survival and safety — between knowing fear and learning peace.

So how can “as above, so below” become a reality for someone who has only ever known fear and suffering?

How does a body that has never felt safe learn to trust safety?

This is the lifelong work of trauma recovery. Alignment doesn’t come through striving or forcing calm. It begins with gentle awareness — the smallest moments of safety, repeated often.

A steady breath.

A kind gaze.

A tone of voice that doesn’t demand.

A space where the body isn’t braced for impact.

These moments may seem insignificant, but they are everything. They are the entry points to realignment.

When the nervous system begins to feel safe — even for seconds at a time — the mind starts to open. The body begins to soften. The soul starts to remember what peace feels like.

For those who have lived on guard, constantly predicting and pre-empting the worst, this process takes immense patience and compassion — both from themselves and from those who walk beside them.

So how do we reach to teach?

Not through correction, and not through preaching calm to those who have never felt it.

We reach through embodiment.

We teach by becoming the example — by holding consistent compassion, modelling regulation, and creating spaces where calm is felt, not enforced. When survivors are met with presence instead of pressure, their nervous system begins to sense that safety might be possible.

“As above, so below” isn’t a rule or ideal to attain — it’s a rhythm that re-emerges when the mind, body, and soul are no longer at war. When we align the internal and external, Heaven and Earth, reality and perception, we rediscover the flow that trauma once interrupted.

It’s not instant. It’s not easy. But it’s possible — one safe breath at a time.

So I wonder… where are you on your own journey of “as above, so below”?

What does alignment look and feel like for you — in your mind, your body, and your soul?

Filtering Reality: Attention, Awareness, and the Expanding Mind

In The Doors of Perception, Aldous Huxley described something extraordinary.

Under the influence of mescaline, a naturally occurring psychedelic compound found in the peyote cactus, his brain activity didn’t increase — it decreased — yet his perception expanded. Colours deepened, time slowed, and he felt profoundly connected to life itself.

Peyote has been used for thousands of years in Indigenous ceremonial practices across the Americas, valued for its ability to open the mind to spiritual awareness. Huxley’s experiment was part of his own search to understand consciousness beyond the limits of ordinary perception.

From that experience, he proposed something radical: perhaps the brain doesn’t create consciousness — perhaps it filters it.

He suggested that the mind’s natural state is vast, but the brain acts as a reducing valve, narrowing what we perceive so we can survive without being overwhelmed by the full flood of reality.

It’s a beautiful idea — that what we experience as “ordinary consciousness” may only be a fragment of what’s possible.

The Everyday Filter

We can all see this filtering in our daily lives.

Imagine sitting quietly, paintbrush in hand, working on a tiny die-cast model. The hum of the fridge fades, the world disappears, and every ounce of attention narrows into the curve of the brushstroke. The brain is doing what Huxley described — filtering.

Filtering helps us focus, survive, and function. But the same mechanism that allows deep concentration can also keep us disconnected from the wider richness of life.

It’s the paradox of being human: we need the filter to survive, but we thrive when we remember to widen it.

ADHD and the Leaky Filter

For people with ADHD, that filter behaves differently.

The ADHD brain often struggles to separate what’s important from what isn’t. Sounds, lights, textures, emotions — everything arrives at once. It’s not a lack of discipline, but a different neurobiology. The brain’s “gatekeeper” lets more sensory input through, which can lead to overstimulation and fatigue.

And yet, ADHD also brings moments of hyperfocus — deep, sustained immersion in something that captivates the mind completely.

This is the paradox of the leaky filter: it can flood us or free us, depending on context.

The ADHD experience reminds us that attention itself is an art — not always about controlling the mind, but learning to meet it with compassion when it overflows.

Autism and the Precision Filter

Autistic and neurodiverse people experience attention differently again.

Many describe a world of intense detail — where patterns, sounds, and textures stand out vividly. The filter is tuned in a unique way: sometimes wide open to sensory information, sometimes tightly focused in what we might call hyperfocus or flow.

This precision of attention can be a gift — a kind of deep consciousness that others overlook — yet it can also lead to sensory overwhelm when too much enters awareness at once.

Autistic focus, in this sense, shows us that consciousness isn’t one fixed shape.

It varies across individuals, each brain filtering the world through its own rhythm, each mind revealing a different facet of reality.

Overstimulation and the Modern Mind

Our digital age has turned attention itself into a commodity.

Every scroll, ping, and notification competes for a slice of our consciousness, training our filters to stay half-open all the time.

Doom-scrolling keeps the RAS — the brain’s attentional gatekeeper — in constant vigilance, feeding it an endless stream of alerts, alarms, and emotional triggers.

The result?

A society of anxious minds, overstimulated yet undernourished.

We’ve learned to mistake constant input for awareness, when in truth it narrows the mind, reduces empathy, and fragments consciousness.

For children and young people, whose filters are still developing, this can be especially damaging. Their sense of safety and identity is being formed through algorithms rather than authentic connection — through comparison rather than compassion.

The Reticular Activating System and Survival Awareness

The Reticular Activating System (RAS) sits at the heart of how we filter the world. It decides what information reaches conscious awareness. Normally, it lets in only what seems relevant to our goals — but under threat, it instantly recalibrates.

I remember a day, long ago, when I experienced this with stark clarity.

An abusive partner’s footsteps sounded on the floor above me — heavy, deliberate, charged with anger. In that moment, my awareness shifted.

Time slowed.

Every detail became amplified — the creak of the floorboards, the position of my children, the space between one breath and the next.

That was my RAS and survival brain working together.

The amygdala had sensed danger, flooding my body with adrenaline. My RAS tuned in to only the most vital information: sound, timing, escape.

In that frozen moment, I noticed the smallest thing — a single drip of wine running in slow motion down the side of a glass.

It was surreal, almost suspended in time, and I later wrote about it in my book When I’m Gone.

That image has never left me. It captured the paradox of trauma — how the mind can expand in focus even as the body prepares to fight, flee, or protect.

That was my RAS and survival brain working together — the amygdala sensing danger, the RAS focusing attention, adrenaline flooding my body to act.

Within seconds, I had moved my children out of harm’s way, moments before his rage erupted and a table crashed across the room.

Terrifying, yes, but precise. A pure expression of the body’s will to protect life.

It wasn’t thought. It was instinct — a focused, timeless state that felt both terrifying and sacred. My consciousness didn’t expand in beauty; it expanded in survival.

And it saved us.

The Cost of Survival Mode

After experiences like that, the RAS can stay switched on.

It keeps scanning for danger, long after the threat has passed.

A creak in the floor, a raised voice, even a subtle shift in energy can send the body into high alert. This is trauma’s residue — the nervous system learning from history and trying, tirelessly, to keep us safe.

But when the brain filters for danger more than for life, the world begins to feel smaller.

Anxiety, hypervigilance, and exhaustion take hold.

The filter becomes too narrow, the mind too guarded, and consciousness contracts into survival.

When Safety Feels Unsafe

When the RAS has been tuned to threat for a long time — perhaps since childhood — even safety can feel unsafe.

The nervous system becomes so accustomed to reading danger that calm can feel foreign, suspicious, even unbearable.

Kindness lands heavy on a body that has learned to brace for harm.

A gentle word — “you’re looking really well today” — can cause the same visceral recoil as a threat, because the body doesn’t yet recognise tenderness as safe. It reads tone, energy, and proximity through a lens calibrated to survive cruelty.

Just as survivors flinch at sudden movement, they can also flinch at affection, praise, or care. The mind may understand it, but the body contracts, narrowing awareness again, pulling back behind invisible walls.

It isn’t rejection — it’s protection.

This is why healing can’t happen through the mind alone.

Traditional “mental health” work often focuses on thoughts and beliefs, but trauma lives in the body — in fascia, breath, posture, and heartbeat. The nervous system must relearn safety through direct experience: slow breath, grounded movement, eye contact, connection, presence.

Integration is what allows safety to stay.

When mind, body, and soul begin to work together again, the filter shifts — no longer tuned only to threat, but to connection, curiosity, and love.

Expansion Through Stillness

Healing begins when safety returns — not just around us, but within us.

Through practices like mindfulness, breathwork, prayer, nature, art, and even simple rest, we teach the RAS that it can soften its grip.

Modern neuroscience now shows what ancient wisdom has always known: when the body feels safe, the brain’s “default mode network” quiets, and awareness naturally expands.

Stillness doesn’t empty the mind; it reveals it.

In that openness, we rediscover connection, creativity, and compassion — the very qualities trauma tries to erase.

Consciousness and the Future of Awareness

If each brain filters reality uniquely — shaped by neurodiversity, trauma, attention, and environment — then consciousness itself is not fixed, but fluid.

It evolves with our experiences, our technologies, and our collective values.

When education rewards performance over presence, when media feeds fear more than curiosity, our shared awareness narrows.

But it can also widen again — through self-understanding, empathy, and intentional slowing down.

Through reclaiming the power to direct our own filters rather than letting them be hijacked by survival, distraction, or design.

In closing…

Huxley believed the brain’s purpose was to limit consciousness so that we could survive it.

Perhaps our task now is to learn to use that filter wisely — to know when to focus and when to expand, when to protect and when to open.

Survival once required narrowing the mind; thriving now requires widening it.

Awareness grows the moment we notice what’s shaping it — the scroll, the noise, the pace, the fear — and choose, even briefly, to pause.

In that pause, consciousness awakens.

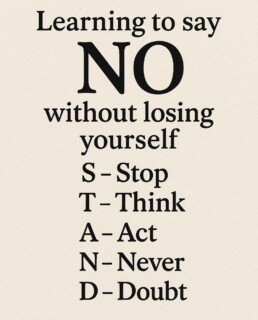

For me, this is where STAND becomes a daily practice of presence:

Stop — pause long enough to notice what’s shaping your awareness (the scroll, the noise, the pace, the fear).

Think — name what your nervous system is doing (threat-focusing or safety-widening).

Act — choose a regulating step: breath, grounding, connection, a kinder word.

Never Doubt — trust your inner truth and the body’s wisdom that safety and connection can return.

Survival required contraction.

Healing invites expansion.

Awareness begins the moment we Stop and make space to Think, Act, and Never Doubt the possibility of wholeness.

In that pause, consciousness awakens — and maybe that’s where the next evolution begins, not through more information, but through presence.

Q. When was the last time you felt truly present — not thinking about life, but living it? - Answers in a journal please 😉

References

Carhart-Harris, R. L., & Friston, K. J. (2019). REBUS and the anarchic brain: Toward a unified model of the brain action of psychedelics. Pharmacological Reviews, 71(3), 316–344. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.118.017160

Christakis, D. A., Ramirez, J. S. B., Ferguson, S. M., Ravinder, S., & Ramirez, J. M. (2018). How early media exposure may affect cognitive function: A review. Pediatrics, 141(2), e20170335. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0335

Crozier, D. J. (2025). When I’m gone: Reclaiming safety, trust & hope after trauma. Self-published via Amazon Kindle Direct Publishing. https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B0DVGJNGTC

Damasio, A. (2018). The strange order of things: Life, feeling, and the making of cultures. Pantheon Books.

Grandin, T. (2011). The way I see it: A personal look at autism and Asperger’s. Future Horizons.

Huxley, A. (1954). The doors of perception. Chatto & Windus.

LeDoux, J. (2015). Anxious: Using the brain to understand and treat fear and anxiety. Viking.

Liss, M., Mailloux, J., & Erchull, M. (2008). The relationship between sensory processing sensitivity, alexithymia, autism, and empathy. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(3), 255–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.04.009

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W. W. Norton & Company.

Posner, J., Park, C., & Wang, Z. (2014). Connecting the dots: The cerebral basis of ADHD and attention regulation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 15(2), 65–81. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3654

Raichle, M. E. (2015). The brain’s default mode network. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 38, 433–447. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-neuro-071013-014030

Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. W. (2015). The science of mind wandering: Empirically navigating the stream of consciousness. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 487–518. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015331

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

Learning to Say No: Reclaiming Ourselves Through the STAND Framework

How We Learned to Fear “No”

From early childhood, many of us were conditioned to equate obedience with love. When we complied, we were rewarded with affection or approval.

When we resisted, expressed anger, or said no, we were met with disapproval, punishment, or withdrawal.

We didn’t just learn this from what people told us — we learned it from what we saw.

We watched the adults in our lives say yes with a smile, even when their eyes said no.

We saw them appease, overextend, and agree to things that clearly made them uncomfortable.

We noticed the change in their energy once the visitor left or the phone call ended — the sighs, the frustration, the quiet resentment that followed the polite compliance.

As children, we absorbed that contradiction: the mask of persona — the belief that being kind meant being compliant.

We saw incongruence modelled as normal: the split between how we feel and how we present ourselves to stay safe or accepted. And from that, we learned our first survival pattern — self-abandonment disguised as kindness.

Bit by bit, our nervous systems adapted. We became experts at scanning for disapproval, reading emotional cues, and adjusting ourselves to maintain harmony.

For many, that became the template for love: keep others comfortable, and you might stay safe.

But what begins as protection in childhood often becomes a prison in adulthood.

This became the start of a lifelong pattern: people-pleasing as protection.

The Adult Consequences — When Saying “Yes” Hurts More Than “No”

In our personal lives, this conditioning often shows up as:

- Feeling responsible for other people’s emotions

- Struggling to set boundaries in relationships

- Feeling anxious when others are disappointed

- Over-apologising or explaining ourselves

At work, it might look like:

- Taking on extra tasks to avoid letting others down

- Feeling invisible or undervalued but too afraid to speak up

- Saying “it’s fine” when it isn’t, to avoid conflict

- Burning out while smiling through it

Each of these moments is a quiet act of self-abandonment — a way of saying, your comfort matters more than my wellbeing.

The Hidden Cost — When Manipulation Finds Our Weak Spots

Unfortunately, those who seek to control, dominate, or exploit often recognise this pattern of compliance.

They sense the need to please and use it to maintain power.

It might sound like:

“You’re overreacting.”

“I thought you were kind — why are you being difficult?”

“If you loved me, you’d do this for me.”

These are not innocent phrases; they’re tools of manipulation designed to trigger our deepest fear — the fear of rejection.

When someone learns that our sense of worth is tied to approval, they can press that button repeatedly until we no longer trust our own perception of reality.

This is why learning to say “no” is not simply a communication skill — it’s an act of liberation.

The Process of Recovery — Learning to STAND

Healing begins when we notice the automatic “yes” rising and choose to pause.

That moment — the gap between reaction and response — is where freedom begins.

The STAND framework offers a simple way to practise that pause:

S – Stop.

Notice what’s happening in your body before responding. The tight chest, the quickened breath, the urge to fix — all are signs you’re about to self-abandon.

T – Think.

Ask: Is this my responsibility?

Am I doing this from love or fear?

What’s mine, and what belongs to the other person?

A – Act.

Choose a response that honours your truth — even if it’s uncomfortable.

A boundary said calmly is more powerful than an argument shouted in frustration.

N – Never

D - Doubt.

Never doubt - that protecting your peace is self-care, not selfishness.

You are allowed to exist without explanation.

The Outcome — Reclaiming Connection, Not Losing It

As we learn to STAND, we stop reacting from fear and start responding from truth.

We begin to separate other people’s emotions from our own.

We build relationships based on authenticity rather than appeasement.

We rediscover that belonging doesn’t require disappearing.

Each time we pause, breathe, and choose differently, our nervous system learns a new message:

“I can be safe, even when someone is disappointed.”

That’s where real connection begins — not in saying yes to everyone, but in saying yes to ourselves.

In Closing -

It’s not about becoming hard or detached.

It’s about becoming whole — rooted in integrity, compassion, and self-respect.

When we learn to STAND, we show others how to meet us honestly too.

And that’s where true belonging lives.

Each time you say no without guilt, fear, or shame, you reclaim a piece of yourself that was lost in appeasement.

You remind your nervous system that safety isn’t found in compliance — it’s found in congruence.

If you’d like to learn more about STAND and how to say no with confidence — without guilt, fear, or shame — join our workshop:

STAND: Parents as Protectors, in partnership with Safeguarding Fundamentals.

To register or find out more, visit our website or send a direct message with “DMSTAND” to connect.

Because protecting yourself and those you care for isn’t defiance — it’s self-care.

https://apositivestart.org.uk/stand-parents-as-protectors/